[ad_1]

Crisis Access Points have surpassed expectations during the first year of a state program intended to ease burdens on first responders, said Lauren Bruce, Compass Health Network senior director of crisis stabilization.

The points, formerly referred to as Crisis Stabilization Centers, are sites where people experiencing a behavioral health crisis can access care without having to go to an emergency room, or without having an encounter with law enforcement.

“They have gone really great. It’s been a really wonderful project,” Bruce said. “We had a rough idea of what we were getting into when we first started. It’s evolved and transformed and is really fantastic.”

Starting somewhere

Until recently, law enforcement’s only choices were to transport someone experiencing a crisis to a hospital or a jail, especially during weekends or after hours.

The institutions aren’t always the most appropriate destinations for patients, according to staff at Compass Health Network. But access points are spaces where patients can receive the care they need. They are not “drop-off” sites. The points are intended to connect patients to case workers and mental health professionals, if they are needed.

Expanding on existing access points that were mostly localized public/private partnerships, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson included about $15 million in his 2021-22 budget to establish six new points and support five already-existing sites (like the Kansas City Assessment and Triage Center, Springfield’s Burrell Behavioral Crisis Center and Joplin’s Ozark Center). Seven actually opened in 2022.

The points are intended to be places to where people undergoing crises may be diverted, rather than ending up in emergency rooms or involved with law enforcement. Clients are paired up with case managers, who are responsible for assuring the clients receive follow-up care.

One of the new access points is in Jefferson City.

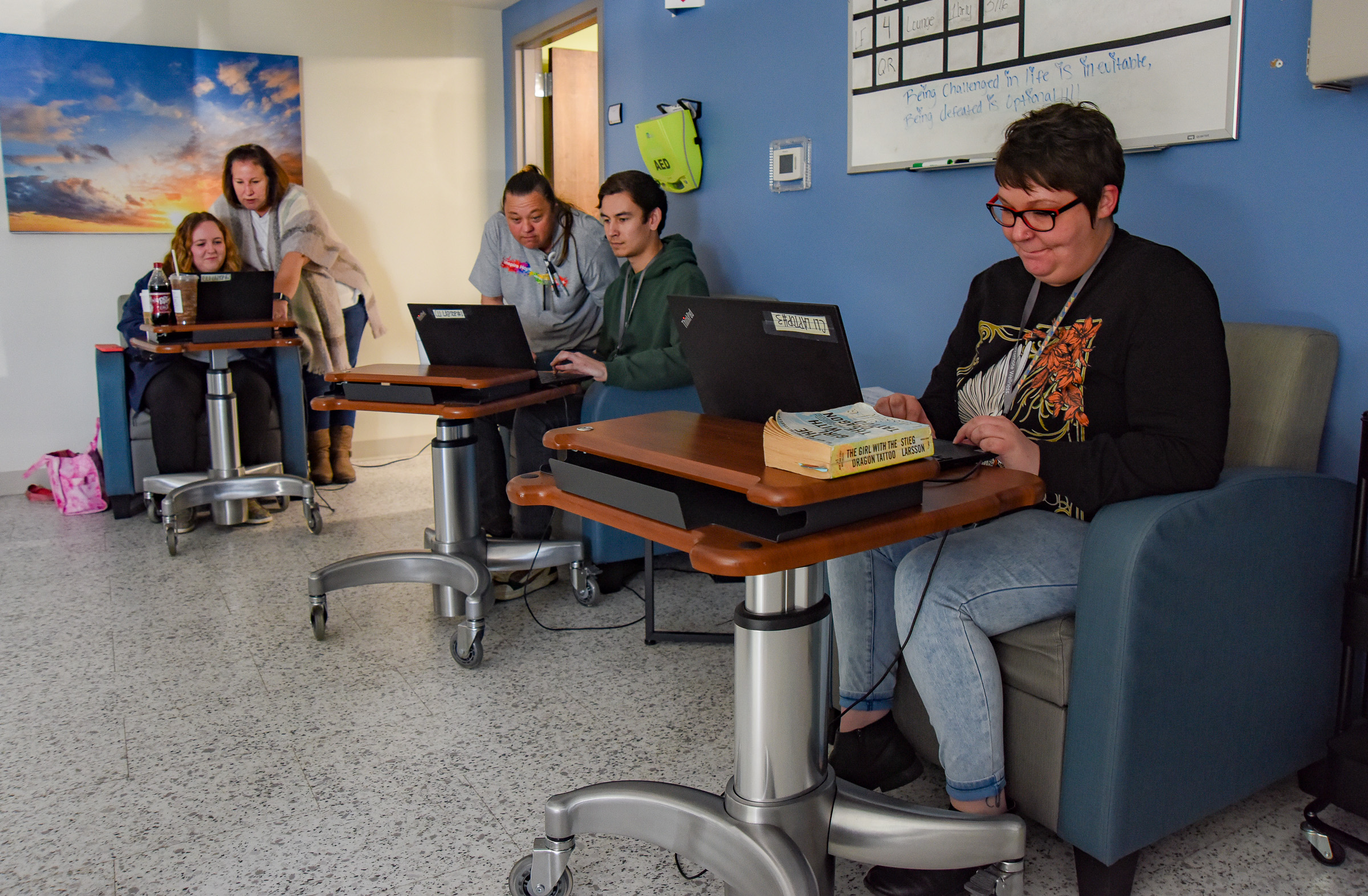

The Jefferson City facility, which occupies the bottom floor of a Compass Health office, features four “slots” — recliners where patients may rest or sleep. The access points are mandated to only keep clients 23 hours. Behavioral health clinicians may triage patients who arrive at the access points. Patients entering may shower, get something to eat and get their clothes laundered.

Patients may receive new (to them) clothes.

“You never know — sometimes a hot shower and a pair of sweatpants is the best way to kind of reset your day,” Bruce said. “We have a lot of folks — they are able to come in. Take a hot shower. Get into comfortable clothing. Go back to the unit and crash out. Then we can start dealing with whatever that problem is.”

A year of care

During its first year in Jefferson City, the access point served people in 984 encounters, according to Bruce.

Of those, 740 of the encounters were unique clients, she continued.

Debra Walker, Missouri Department of Mental Health director of public affairs, said there were 19,708 referrals in the state during 2022.

Of those the leading referral sources were: client or self-referral, emergency department or hospitals, family or friend, behavioral health outpatient, law enforcement, local or community organizations, medical outpatient, community behavioral health liaison and emergency medical services or fire departments.

“Law enforcement is our second-highest refer in the (Jefferson City) area, which is wonderful,” Bruce said.

She added having that partnership with law enforcement is essential to getting clients the resources they need in a timely manner. Also, if law enforcement knows to divert people undergoing crises into the access points, it greatly frees up their time.

“We have an interesting data point — what does that cost to the system for people coming to us directly?” she asked. “About $3.6 million has been diverted from that (legal and health) system. If you call 911 with a behavioral health crisis, and they dispatch EMS and law enforcement, there’s cost associated with that. The emergency department — there’s cost associated with that.”

Although the state did not present exact data about causes of referrals to the access points, Walker listed seven leaders: Mental health crisis, substance-induced crisis, co-occurring substance-induced crisis and mental health condition, acute intoxication, suicidal, self-harmful and dangerous to others.

Bruce said conditions people presented with at Compass were of interest to behavioral health professionals. She said 470 (of local encounters) were strict mental health crises and 293 were co-occurring disorders.

“A lot of folks in Missouri are struggling with mental health,” she said. “Substance abuse is still out there.”

Paying the bills

More than 500 clients who arrived at the access point during the first year were Medicaid recipients, Bruce said. She said 230 had no insurance when they arrived.

“We’ve helped them access Medicaid while they were here,” she said. “Medicaid expansion has been wonderful — we’ve been able to get 200 folks get access to Medicaid or the marketplace.”

Insurance status for clients using the access points statewide was the following (there is duplication, so the total exceeds 100 percent):

Medicaid, 29.4 percent.

Uninsured, 24.2 percent.

Veterans Administration, 21.3 percent.

Private insurance, 20.7 percent.

Unknown, 15.4 percent.

Both Medicaid and Medicare, 3.2 percent.

Medicare, 3.1 percent.

Other, 2.7 percent.

Lauren Moyer, vice president clinical innovation at Compass Health Network, said clients have shared their success stories with the provider.

Moyer said an adult female who struggled with addiction for years and was recently evicted ended up at an access point. The woman had a history of relapses, police contacts, emergency room visits and substance use disorder care. But, she never got follow-up care from a case manager.

“After coming to (Compass), she was able to get into residential substance use treatment and then placed into a supportive living situation with continued follow-up care from a case manager,” Moyer said. “Living alone was not healthy for her recovery, and she has been so grateful to have a supportive place to call home. She is now eight weeks sober and loving her sober living situation.”

She said another client — a man who had recently received a release from prison — feared he would go out into the street, abuse substances again and end up dead.

He asked for help, but would not stick around for treatment.

The man returned and entered into outpatient treatment, used a crisis access point several times (when he was “struggling with triggers and cravings”) and participated in outpatient substance use disorder treatment.

He found a job, got housing and reconciled with his fiancee.

Julie Smith/News Tribune

Staff at Crisis Access Point discuss activities and options Friday at the center 227 Metro Drive. The center has been in operation one year in this location and staff has seen some clients through to a successful treatment. Some needs are extensive while others can be handled with a shower and change of clothes. The center is much to many who are grateful they are there and can help in time of need. Seated from near to far are: Lydia Garwood, Jacob Kykuta and Megan Walker, all CLI’s. Standing are Holly Salchow, also a CLI and Lori Fizer, the program’s lead nurse.

[ad_2]

Source link