[ad_1]

An Israeli company is combining artificial intelligence with satellite data in a potentially game-changing method for sequestering carbon on land — and eventually at sea.

In doing so, Albo Climate, which consists mainly of Israeli technology specialists, looks set to contribute to the fight against global warming and climate change by helping to decarbonize the atmosphere in collaboration with environmentalists from overseas.

The Tel Aviv company, founded in 2019, uses data from satellite-mounted sensors to create detailed maps of where carbon is stored, allowing landowners and governments to profit by selling credits to polluting companies.

It does this by first gathering real carbon data collected by hand, such as measuring tree trunk diameters to calculate biomass growth (see below) or analyzing soil samples in laboratories. It does this every time it encounters a new type of habitat.

The company uses machine learning to teach the technology by combining data from satellite sensors — which can scan plants above ground and up to 30 centimeters (one foot) below, where the soil and roots are — with real-world data. It allows him to identify patterns that can serve as a basis for carbon projections in similar settings elsewhere.

“AI has found relationships that humans don’t,” said Ariella Charney, Albo’s chief operating officer.

Part of the Albo Climate team (from left): COO Ariella Charny, CEO Dr. Jacques Amselm, VP AI R&D Prof. Andre Scharf, Marketing Manager Sharona Schneider. (Moshe Jonathan Gordon Radian)

All life on our planet, from humans to the smallest plant, depends on carbon.

Over hundreds of millions of years, nature has balanced the amount of carbon that enters the atmosphere with the amount that is released and stored. Breathing, for example, produces CO2, as do volcanoes.

Plants, as well as seaweed and ocean phytoplankton, make glucose, a carbohydrate, when they photosynthesize. When plants die, they take the carbon with them, eventually turning into carbon storage like coal.

But that balance has driven carbon dioxide emissions through the roof due to industrialization. When coal or wood is burned, for example, it releases previously stored CO2.

The world is committed to – at least in principle – reducing carbon dioxide emissions to reduce global warming.

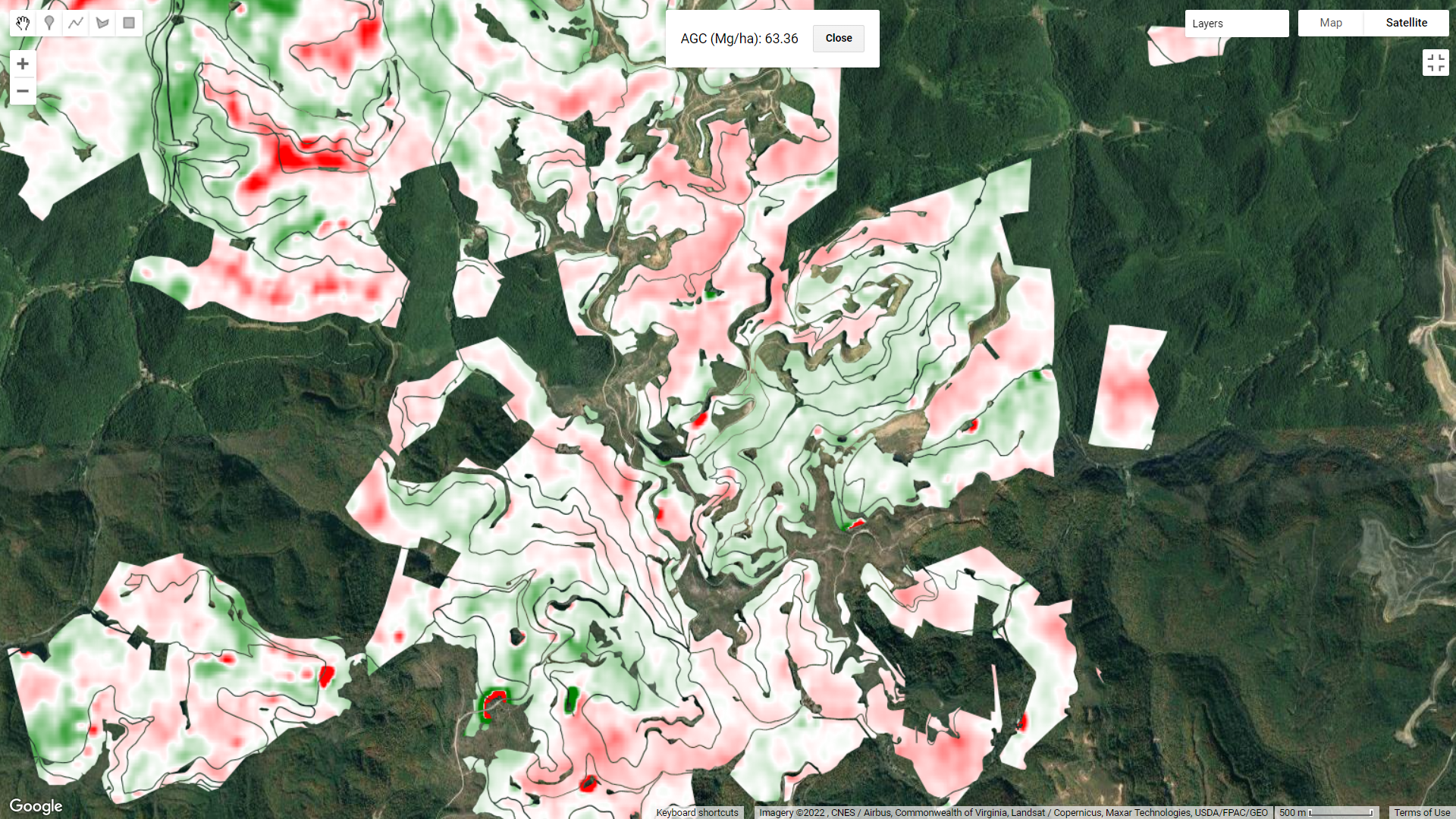

A screenshot of an interactive map showing areas of African forest where above-ground carbon is decreasing in red, increasing in green, and showing no change in white. (Courtesy: Albo Climate)

For those unable or unwilling to cut emissions, cap-and-trade systems are in place, allowing them to pollute and sequester the same amount of CO2 they emit.

Most of the companies that store carbon and sell credits are based on nature, and their methods include everything from protecting forests to using sustainable agricultural methods. Using Albo data, you can get a good idea of how much carbon you are storing and how much you can offset.

Albo is not the first to attempt to map carbon storage. In the year In 2018, the Food and Agriculture Organization published what it said was the first global carbon map, and others have released maps.

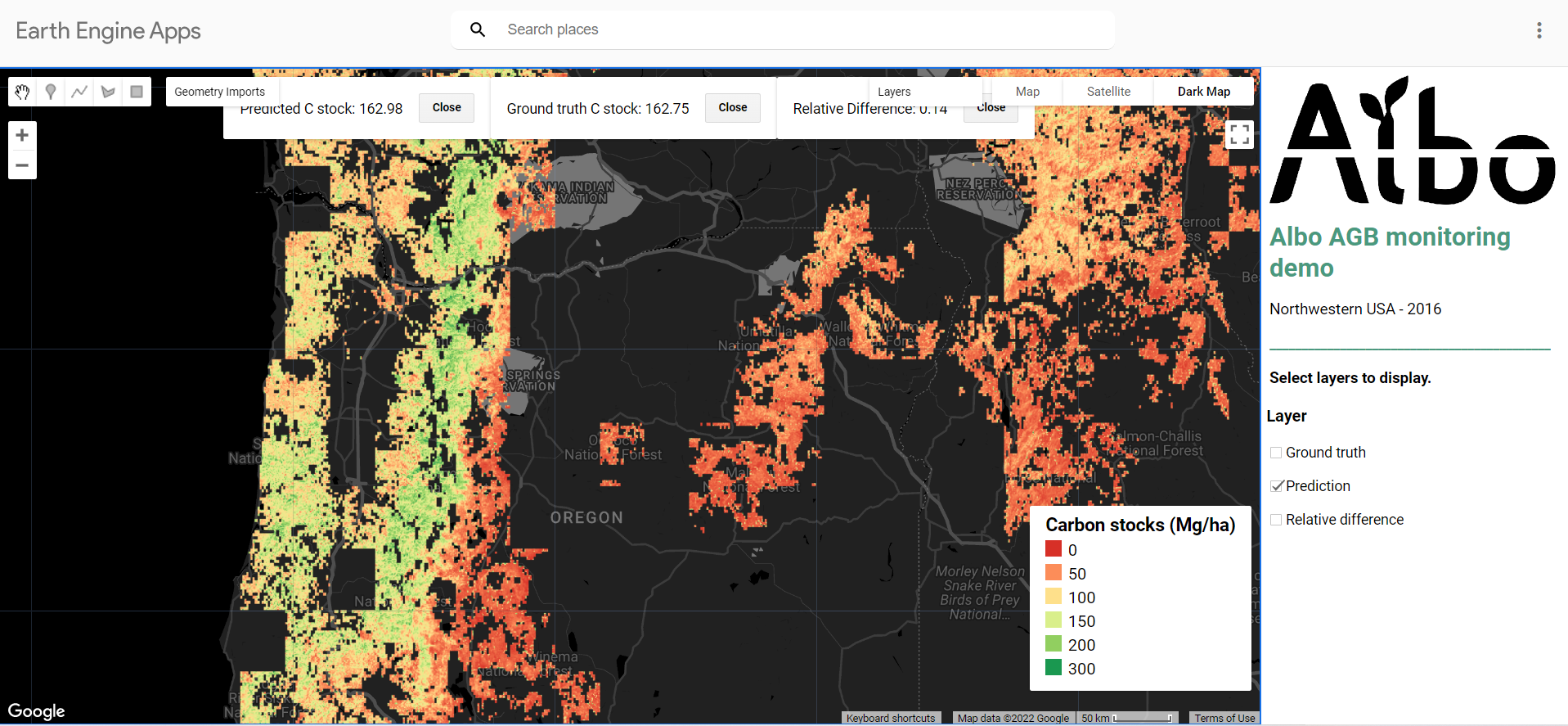

But according to Charney, these are general and granular compared to Albo’s maps, which can predict the carbon value of up to 100 square meters of forest (just over 1,000 square feet), with remarkable accuracy.

The company is currently trying to achieve a resolution of 50 centimeters squared (a quarter square meter or 2.7 square feet) per pixel.

Among the advantages Albo offers, according to founder and CEO Jacques Amsalam, is that it’s faster and cheaper than handheld measuring methods, doesn’t involve breakable hardware, and can measure hard-to-reach areas like tropical forests. It results in a visual, graphical format that is easier to understand and often scientifically accurate than long, written reports.

A screenshot of an interactive map showing aboveground carbon stocks in parts of the Pacific Northwest. (Courtesy: Albo Climate)

In addition, it can regularly monitor (once a year) to ensure that the forest, which is sequestering carbon and making money, is not logged or burned and does not emit carbon dioxide.

An international company that verifies the validity of carbon credits is close to completing the approval process in Albo.

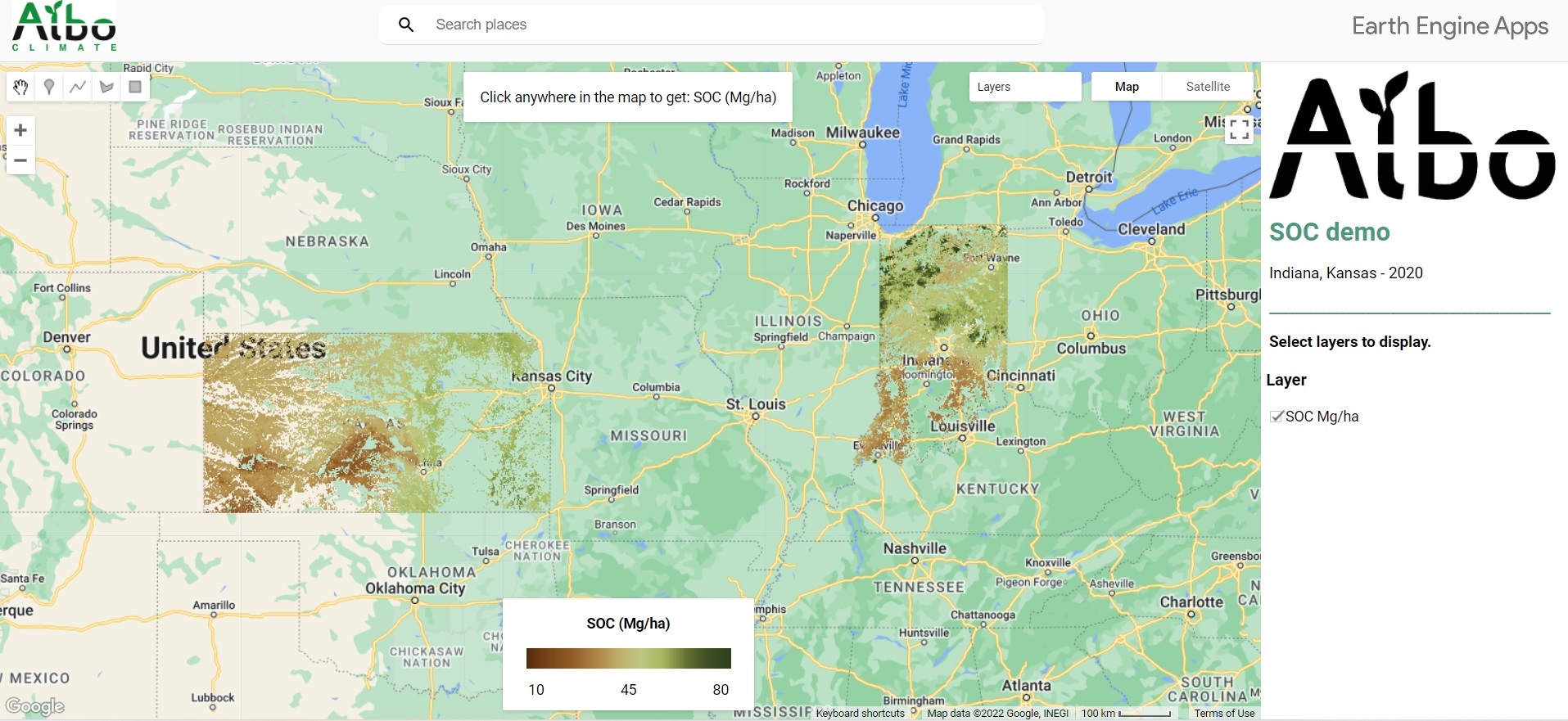

Screenshot of an interactive map of parts of the US Midwest. Green indicates high soil organic carbon (SOC) values and brown represents low ones. (Courtesy: Albo Climate)

However, the company has signed several agreements to provide its mapping services.

These include exploring Ecuador’s Choco Andino de Pichincha Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Taranis, an Israeli precision agriculture company based in the US, that uses carbon-based biomass to grow corn and soybeans in the US Midwest; developing a new voluntary carbon register for forest-based projects for Finnish sustainable finance company Liquidi; and tracking the biomass of vulnerable tropical forests in several sub-Saharan African countries, starting with Cameroon, for the Mauritius-based clean energy company Tembo.

A screenshot of an interactive map showing annual carbon loss and carbon gain in a forest in Kentucky, USA. Red stands for loss, green for gain and white for no change. (Courtesy: Albo Climate)

The Congo region, south of the Sahara, is home to the second largest rainforest after the Amazon, but it doesn’t get as much attention. According to environmental news site Mongabay, annual deforestation has exceeded one million hectares (2.5 million acres) in recent years.

Mountain gorillas in Virunga National Park, Democratic Congo. (Cai Tjeenk Willink, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

It is unclear whether the money generated by carbon credits can beat the sums from fossil fuel, mining and logging corporations.

According to Charney, there are currently only a few dozen companies worldwide offering remote sensing technologies for carbon measurement, with very few combining above-ground and below-ground measurements.

Albo is currently working on initiatives such as kelp farming to measure ocean-based carbon sequestration. It is in advanced discussions with an Israeli university to deploy several satellites for climate research and data collection.

Currently, Albo uses data collected by radar, hyperspectral cameras and laser-guided lidar technology to take most of the open source data from existing satellites.

From right: Shelley Dvir, Deputy Director of Business Roundtable Israel, Victor Weiss, Associate Director of the Climate Recovery Center, Perumal Arumugam, UNFCCC Group Global Carbon Market Development Leader, and Foreign Ministry Special Climate Envoy Gideon Behar at Israel’s first Carbon Sequestering Conference, Shefaim June. 30th 2022 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Last month, Perumal Arumugam, the UN’s top official on developing rules for a global carbon trading market, told Israel’s first conference on carbon sequestration that he saw unique global potential in Albo’s climate production and drip irrigation company. Netafim has developed a unique water and methane efficient method for irrigated rice cultivation.

Albo Climate was originally designed to map wetlands that could be drained to reduce mosquito-related diseases such as Zika. The name is taken from mosquito. Ades albopictuS.

After global investment firm Techstars chose Albo for funding, the company decided to focus its technology on climate instead. It is now seeking Series A investors.

[ad_2]

Source link