[ad_1]

The writer is editor-in-chief of MoneyWeek

Let’s say you’re unemployed and someone offers you $ 15 an hour to work 40 hours a week as a shift manager at McDonald’s in the United States. That would give you $ 600 a week. It is not a fortune. It’s not horrible either. So all other things being equal, if you need a job, you’ll probably take it on. But what if someone else offered you a little over $ 600 a week if you didn’t take them? Maybe $ 650: to stay home. I guess it’s you you might think twice.

This could be part of the explanation of the problem that American companies have at the moment to hire. For much of the last 18 months, the US Government not only has it eliminated one-off stimulus checks on the general population, but it has also offered vastly outdated unemployment benefits. People have been able to claim more and for longer than ever (39 weeks instead of 26 weeks). The average weekly unemployment benefit nationwide now exceeds $ 600, and some states pay more than $ 700.

The figures are not as good as in the previous part of the pandemic, when the average replacement rate (the percentage of your income replaced by loss of employment) went from 48% to 145% before the pandemic. But it does offer a reason for many people to decide, as Intertemporal Economics says, that “expected employment income is lower than government transfers and the value of leisure time.”

This may be particularly the case when the pandemic savings cushion that families have accumulated is added, cash that allows them to wait their time before re-entering the market. There may also be a short-term wealth effect here: If the price of your home increases by 10%, you may have less financial pressure in the long run. Note that a slightly higher percentage of Americans said they felt financially secure in 2020 than in 2019.

The figures show the result of all this: a lack of supply in the labor market. April employment figures were shown 75 percent fewer people returning to employment than most analysts expected. This cannot be put on the doorstep of demand: there are many vacancies. There are other issues as well: think about health issues (who wants to leave the house unvaccinated?) And daycare issues (not all U.S. schools are open). All of this is fair (there’s a reason 60% of job seekers want it remote). But these last two points surely only come into play for many households due to improved benefits and pandemic savings.

All of this has been difficult to measure during the pandemic. But there is healthy research that suggests that the more people are paid for not working, the less they work and we will soon find out if this has a good post-coronavirus. As Capital Economics points out, some U.S. states have chosen not to participate in the best federal programs (“incentives are important,” says the Montana governor), which could explain a recent “faster decline in unemployment claims.” “.

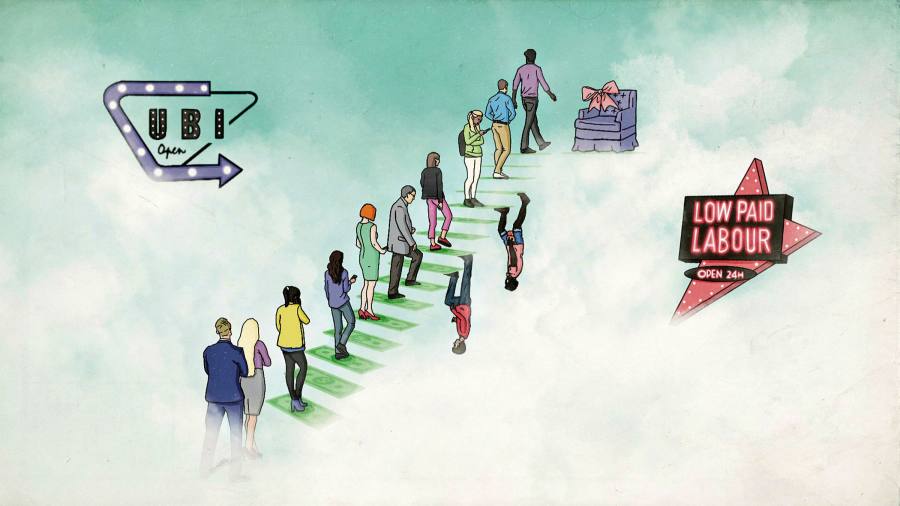

All of this may seem obvious. But it is a problem for those who believe in a universal basic income (UBI) and who believe that the pandemic should be the catalyst that would accelerate its introduction in developed countries. The basic premise of the UBI is that if you can find cash to give everyone an unconditional and untested income to cover all their basic needs, they will become happier, healthier, more productive and, most importantly, less likely. of being unemployed.

It’s a beautiful idea. But beyond the very obvious cost issue, a problem arises: there have been many small experiments, none of which have produced tests that work. The only randomized randomized trial performed nationwide was in Finland A few years ago. There was a clear finding: those earning the basic income were much happier than those in the control group. This is not surprising: it is difficult to imagine that free money makes many people less happy. However, in terms of employment, there was no clear conclusion.

You could argue that a “real UBI” has never been tested: most experiments and promises are more about offering a guaranteed minimum income to a limited number of people. Witness the recent mention by the Scottish Government of a minimum income of £ 37,000 if it achieves an independent Scotland. And you could argue that when it comes to free money, the time scale can make a big difference. If you know you’re getting $ 600 a month for free for three months, you can choose to lift your feet. If you know it’s forever, you’re probably more likely to come up with a long-term career plan.

What cannot be done is to argue that we now have more evidence that a UBI would be good for employment than it was two years ago. Some fans might say that it doesn’t matter: there’s a thread that believes automation will destroy the job market, turning UBI into a simple facilitator of better leisure.

But if that’s your argument, you need to make sure you’re right at work. Because one thing the pandemic has taught us is that if you give people the kind of financial support that allows them to withdraw labor, probably a good number of them. And that doesn’t help anyone in the long run. Just ask 44% of small American businesses that say they can’t find anyone to fill the jobs they offer.

[ad_2]

Source link