[ad_1]

Fast-growing fintech company Block is down 78% after $130 billion was wiped off its market value.

Many will have to follow Klarna’s lead before the reboot fully kicks in. Although there are some signs that people are becoming more realistic about reviews, “we don’t have the full puking it takes yet,” Wolff said.

“A lot of companies deny price changes until they run out of capital,” says David Cowan of Bessemer Venture Partners, a US venture capital firm.

The day when venture capital catches up with reality will, when it comes, be a watershed for the startup sector. Investors of all stripes have flocked to the VC clubby world in recent years, chasing high-growth companies on the public stock market.

Much of the investment flowed in last year as valuations of private startups peaked. Hedge funds, private equity firms, sovereign wealth funds, corporate VCs and mutual funds provided two-thirds of the funds that went into investing globally last year, according to data provider PitchBook.

If those bets turn sour, it could lead to a retreat of many newcomers drawn to investing. This, in turn, could cause a shock to the sector, which has experienced ever-increasing levels of capital.

While annual investment topped $100 billion in the US in the late 1990s, recent venture growth rates have slowed. By comparison, the amount of funding that went into US tech startups last year was $330 billion. That’s twice as much as last year, which itself was twice as much as three years ago.

The flood of money into the private markets has been matched by an equal flood of money into IPOs.

According to American investment manager Coates – one of the new “crossover” investors who moved from the public markets to the VC world – US$1.4 trillion was invested in promising growth companies last year, half in the form of venture capital and half in IPOs. That one-year increase was nearly $1 trillion more than the average of $425 billion raised over the past decade.

Fear of losing

Buoyed by this massive wave of capital, many venture capitalists have conceded that their market has lost the race to invest at any price – even though most want to claim their own money, leaving behind the worst possible returns.

“If there was one word to describe it, it was FOMO,” said Eric Vishria, a partner at Benchmark Capital in California. The “fear of missing out” indicated that the market was tight at the top. It wasn’t just the high price that investors were prepared to pay to avoid missing the boat: the due diligence period was too short and the safeguards that investors built to protect their investments fell by the wayside.

The steady economic expansion and relaxed monetary conditions that followed the financial crisis a decade ago led many investors to view venture capital as a one-way bet, says Vishria. “The right answer for every company over the past 12 years has been capture and distribution. [the shares] Later,” he adds.

“The incentives are geared towards taking companies private and doing bigger and bigger rounds. [of funding]Phil Libin, Evernote’s CEO and venture investor in Silicon Valley, added.

For the company’s founders and employees, as well as the venture firms that back them and the limited partners that provide capital, it looks like a gravy train. As valuations rose, companies set up stock trading programs to raise money for employees and executives, and investors were able to adjust their prices with each new round of capital.

As a result, Vishriya says, the venture capital industry has been overwhelmed. Many companies have been around longer than usual for start-ups, drawing private investors instead of going public.

Venture fund volume exploded as investors pumped in ever-greater amounts of capital. And investment discipline loosened, with VCs spreading their bets across sectors rather than trying to identify the small number of big winners that traditionally provided the lion’s share of the industry’s profits.

New investors who have made the pitch like a balloon of venture investments include SoftBank’s Vision Fund, which has just pumped $100 billion into the market. Tiger Global, which spread its bets widely, at one point had more stake than any other investor in the US$1 billion startup. Both later announced heavy losses: Vision Fund reported a one-year loss of US$27 billion in May, the same month Tiger was reported to have lost US$17 billion.

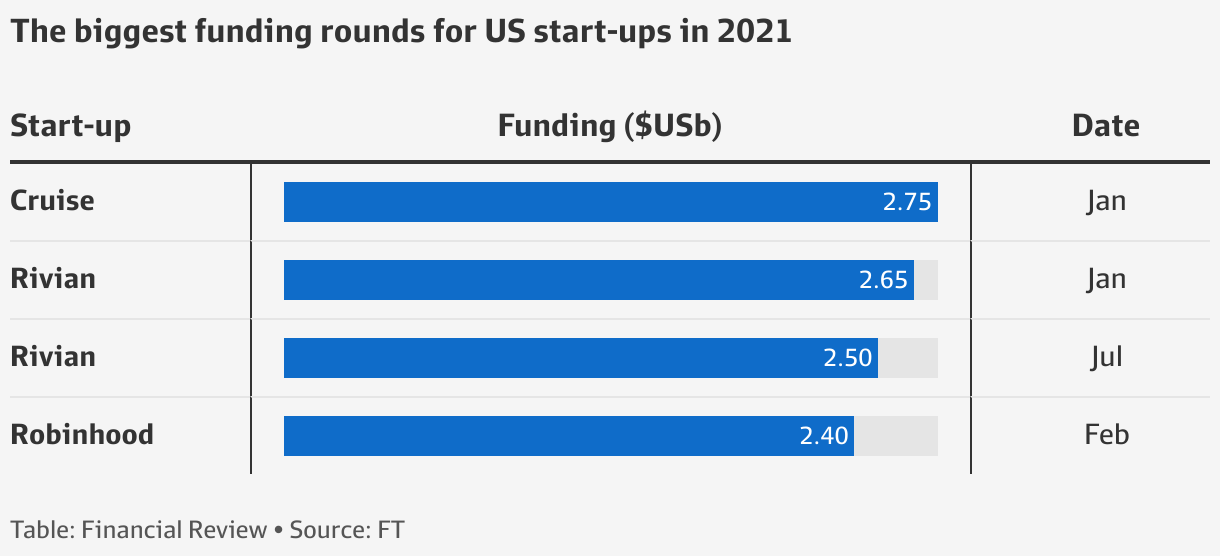

At the height of the boom, investors raced to back significant scientific breakthroughs like nuclear fusion, from electric vehicle companies like Rivian, which raised more than $5 billion last year, to fringe technology bets.

“The introduction [interest] It was crazy.” Two or three unsolicited financing offers a week, said Jeremy Burton, a former Oracle executive who now runs Observer, a private software company. Those deals have stalled, he added — as entrepreneurs and investors wait for the reality to sink in and for a new consensus on valuation standards to emerge in the venture market. It is a reflection of the deep cold that has fallen upon it.

High risk projects

Capital exploration rapidly pushed new fields of science. Like quantum computing and driverless cars, they include “moonshot” projects that were once considered too risky or long-term even for venture capital funds, typically with a seven- to eight-year horizon.

Although the truly transformative breakthroughs that investors had hoped for are far from within reach, startups in both sectors have reported great strides.

Block CEO Jack Dorsey, left, with Postpaid co-founders Nick Molnar and Anthony Eisen. Fast-growing fintech company Block is down 78% after $130 billion was wiped off its market value.

That treasure trove also helped open up risky new sectors of the economy to private startups. For example, the amount of money flowing into startups in the commercial space doubled last year to more than $15 billion, according to engineering and analytics company Brisetech. In the middle of the last decade, annual investments were about $3 billion a year.

Private investment has supported new rocket technologies, satellite systems and Earth imaging services. But startups have entered the frontiers of space exploration, says space analyst Laura Forchick. As NASA plans to return to the moon, private companies hoping for a sleepwalk are plotting lunar activities ranging from mining to building cloud computing centers.

“There is more business. [in areas of space exploration and research that were once considered the province of governments]” says Forsyk. “I don’t know if it will be sustainable” if the money dries up.

Venture capitalists have been reevaluating bets in fields that were once among the hottest fields for startups.

Howard Morgan, chairman of New York venture capital firm B Capital, has singled out the tech industry’s efforts to transform the transportation sector as a cause for concern. He says the driverless car and electric scooter companies his firm has invested in don’t seem like they’re going to change the world.

A company B capital invested in the scooter company Bird in 2010. As of early 2020, it was worth nearly $3 billion. After going public late last year and taking the total amount of foreign capital it has raised to $900 million, it has now become a bird. Price is only 142 million dollars. “We realized that maybe the world wasn’t as ready for these things as we thought,” Morgan said.

When asked which sectors are likely to prove the biggest disappointment, most investors list the same handful: America’s fastest-growing food delivery companies, such as Gopuff and Gorillaz, which aim to deliver groceries to customers in 20 minutes. ; Fintechs, which have launched an expensive campaign to build large consumer businesses; And blockchain-based ventures caught in the crypto crash.

In a recent presentation to investors, Coates described the falling expectations of the tech world as a series of dominoes. He predicted a widening spread of losses, starting with unprofitable internet companies and reaching deeper into the crypto and fintech sectors, before feeding into seemingly solid sectors like software and semiconductors.

If such predictions are correct, investors who put their money to work at the top of the market could face a backlash not seen since the dotcom crash at the turn of the century.

During the action, everything is. In the year The median venture fund raised in 1996, when the first Internet boom was gathering steam, has returned 41 percent annually over its lifetime, according to Greenwich Associates, which tracks fund performance. But in the year At the peak of the bubble in 1999, the median fund lost 3 percent per year.

A repeat of that performance could drive away many of the new investors who were recently drawn to the market. But while some, including SoftBank and Tiger Global, end up being less significant forces in the future, several VCs predict that the big investors backing those firms will invest in other vehicles, meaning competition for investment will remain fierce.

Resetting expectations

For most tech startups, meanwhile, the world has now changed dramatically. With a lot of money still sitting in existing venture funds, proven businesses that have no risk from a weak economy can still look forward to raising money at affordable rates.

Elon Musk’s private space company SpaceX was valued at $125 billion in its latest funding round in June, up from $74 billion in April last year.

But most others have no choice but to adjust their goals. The boom in capital raising has put many in the bank through a two- to three-year funding drought. However, uncertainty about when capital will next be freely available, and under what circumstances, has inevitably created caution.

Gopuff, which raised $3.4 billion before the venture capital wave, is one of several well-capitalized startups that have moved to lay off employees and close facilities to save money.

According to a GoPuff investor, the basic unit of business economics – the amount of revenue generated on each order relative to the costs of the order – is healthy. But the expensive growth race that was once the goal of such startups doesn’t make sense when capital is limited.

A similar calculation is being made in the startup world. Payback time is getting shorter. Hyper-growth is not the order of the day.

Investors are used to seeing successful software startups triple their revenue in their first years, says the Burton Observer. On expected reboot, “I’m not sure if this still works”.

As his company moves past the early stages of product development and prepares to increase its marketing spend, he expects less turbulence for growth: “It could be more measurable or more economic growth than growth at any cost.” He says.

“There’s no question, growth is gone at any price for the next few years,” said Morgan of B Capital.

For venture capitalists, it can seem like a big step after the years of travel have come to an end. But there’s a reason for the parity that many say: Rebooting brings the opportunity to pay lower prices for future investments, making startups more financially disciplined and facing less competition from funded rival startups. Deep-pocketed interlopers like SoftBank.

Summarizing his hopes on the benchmark, Vishriya said: “All pretenses and assumptions will disappear. We meet believers and builders.

What makes many investors — by definition among the professional world’s greatest optimists — is a compelling vision to subscribe to. But it’s not yet clear how long it will take to reboot the venture capital market, or how far today’s investors and startups will stand when it does.

– Financial Times

[ad_2]

Source link