[ad_1]

Say “Richard Nixon” and most Americans think “Watergate” and “scandal.” Older and better-readers would also remember him as the man who opened U.S. diplomatic relations with China.

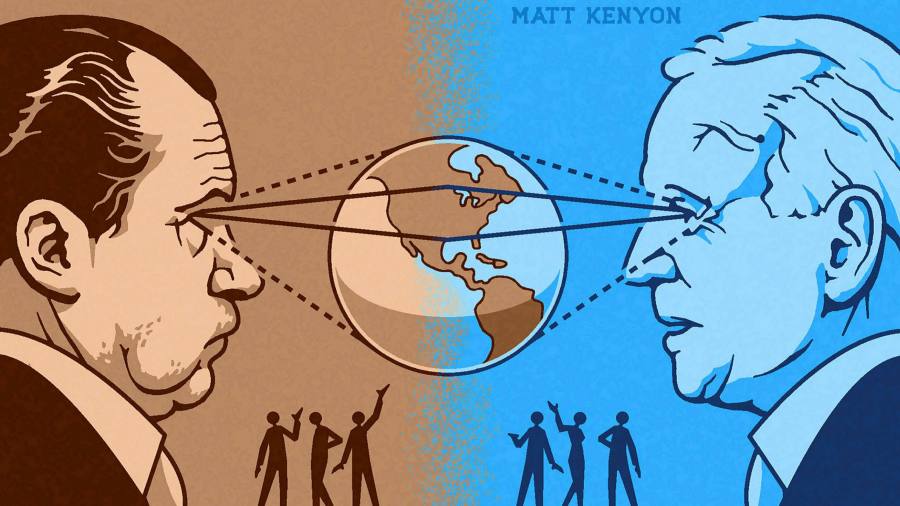

But a deeper analysis shows that the challenges facing the Nixon administration, from changing views on the place of the United States in the world, to the pressures of globalization, to the difficulties of balancing economic policy and outside, they are exactly what President Joe Biden is facing today.

In fact, it could be argued that America is now at a key point quite similar to 1971, the year in which Nixon and his top advisers made the decision to break the link between the U.S. dollar and gold, thus eliminating a fundamental pillar of the Bretton Woods settlement. In fact, this is what Jeffrey Garten argues in his important new book, Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy.

Garten has a unique position to tell this story. He has worked in both diplomacy and finance: he was undersecretary of commerce for the Clinton administration and general manager of the Blackstone group. He has also done numerous interviews with several of the prominent figures who were, as a line of the musical Hamilton goes, actually “to the room where it happened.” The full list of 44 interviewees – from Henry Kissinger and Paul Volcker to Alan Greenspan and George Shultz – is impressive and comprehensive.

Why is this story so relevant today? Because now, as then, an era in the history of the global monetary system is coming to an end. It’s one that no doubt began with Nixon’s decision to break the dollar-gold peg. This helped make U.S. exports more competitive (the “America First” strategy of its day) and resolved the trade imbalance that had arisen due to too many dollars abroad.

It also allowed for much greater leverage by the central bank over the economy. Instead of making politically difficult decisions among various interest groups, Nixon (and almost every administration since then) passed the currency on to the Federal Reserve. Higher interest rates curbed inflation and eventually the dollars returned to the United States.

But instead of tight limits on speculation, this set the stage for the financing of the economy, as securitization instead of lending became the main business of the American financial system, which was now too large to fail.

The Biden administration has this global economic paradigm that must be maintained, in fact, if the president wants to meet his fiscal stimulus plans, which depend on relatively low interest rates and the power of the dollar to allow U.S. debt.

But from inflationary pressures to trade disagreements to the recent popularity of gold, cryptocurrencies and the rise of sovereign-backed digital currencies (such as the digital renminbi, which China hopes will become a much larger part of its own trading and financial system) suggests that we are at a turning point once again.

In the case of the current paradigm to break quickly and unexpectedly, both the dollar and any dollar-based assets could quickly devalue. As the Biden administration considers these pressures and how to manage them, it would be advisable to draw three lessons from Nixonian’s playbook.

First, populism must be balanced with a deep commitment to the Allies. In terms of politics, the Nixon administration was heterogeneous: its Secretary of the Treasury, John Connally, was a rampant nationalist, but national security adviser Henry Kissinger was the last globalist. Having a team of rivals around the table ensured an honest debate on how to balance domestic needs with the realities of the foreign market.

Government-led industrial strategy was also crucial. Who knew that Peter Peterson, a Nixon special advisor, was the best economic planner? He advocated a tougher stance on international competition (urging Nixon to “dissipate any psychology from the Marshall Plan”), but also to a “fix it at home” approach that would include public investment in high growth. technologies, worker recycling i site-based economy – all the features of the Biden approach.

What Nixon did that Biden has not yet done is articulate a vision of what the global economy should be. He rejected the views of his immediate predecessors, John F Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, who, as Garten says, “acted as if there were no limits to the United States’ commitments to peace, stability, and prosperity around the world.” “, or at home. According to Nixon’s alternative view, America would no longer lead the rest of the world alone, but would lead a new coalition of allies, including Germany and Japan.

What began as a “set of hard, unilateral actions” actually ended up increasing America’s involvement in the world, through a better (though imperfect) currency system, a series of nuclear weapons treaties, and new organizations to fight poverty and improve food security. . But that happened only because the administration was able to keep it in view of both national and international needs.

Between Big Tech, state-owned China, and maximum funding, the current situation is arguably more complex. But the fundamental challenge is the same: how can America help itself without leaving the world? Some Camp David-style stage planning would be in order.

[ad_2]

Source link