[ad_1]

If you’ve taken a college economics course, you’ve probably learned a simple history of money. First, people were changing. But the exchange was difficult because a “double coincidence of desires” is needed: I have to want what I have and I have to want what I have. Therefore, people used pieces of valuable metal to facilitate the exchange. Then, paper represented metal and paper took on value. Yes! Money.

That story was selective and very political. As the U.S. government continues to create new dollars and cryptocurrencies compete to see which ones can be appreciated more quickly, we are seeing the renewal of an old argument about the history of money. Whoever controls what we use as money has great power. So there’s always been a strong incentive to say that the only true historical nature of money is, hey, look! That’s what I have!

The phrase double wish coincidence originally comes from Stanley Jevons, a 19th century UK economist who published a detailed history of money in 1890. He came to the particularly Victorian conclusion that the United Kingdom was right: to fix money with gold, a valuable commodity that would naturally flow with trade where it was needed.

Two decades later, Alfred Mitchell-Innes, a British diplomat, established a history that financiers should find comforting. Credit did not follow the money, he argued. Credit was the first. That era money. Archaeologists had found debt records in ancient excavations. In Italy, 3,000-year-old iron discs had been broken in half just after being forged: half the creditor and half the debtor. In Germany, there were similar embedded discs, made of a silver alloy. On the Fertile Crescent Moon, there were clay debt markers, anonymized inside tamper-proof clay boxes. Coins were not the only way to go through a double coincidence.

This week I picked up Jevons and Mitchell-Innes again after reading The Bitcoin standard, by Saifedean Ammous. It begins with the story of Jevons: money is a commodity that improves barter. It is then concluded that gold had been the only suitable money in the past and that bitcoin is its sole heir. The whole story is a simplification. As Ammous simplifies, he makes clear his concerns for the present.

When governments control money, he writes, they inflate its value to make war without paying any price. Inflation is a purely monetary phenomenon: producing more money and getting more inflation. People don’t need to be told to spend; they will do it alone. But we need to encourage people to save, in a rare currency that they continue to appreciate. Under these assumptions, he argues, the only rational defense against the tyranny of government credit money is to buy the rare Bitcoin commodity money.

If you believe these assumptions, please buy Bitcoin. But it’s also easy to find examples in history where they don’t hold up. Sometimes people prudently collected their savings in hard currency. But sometimes the trade took the coins to another place and the people found themselves without hard money, in a deflation that they could not control. In these cases, people did what they always did: they found a way to create money that worked.

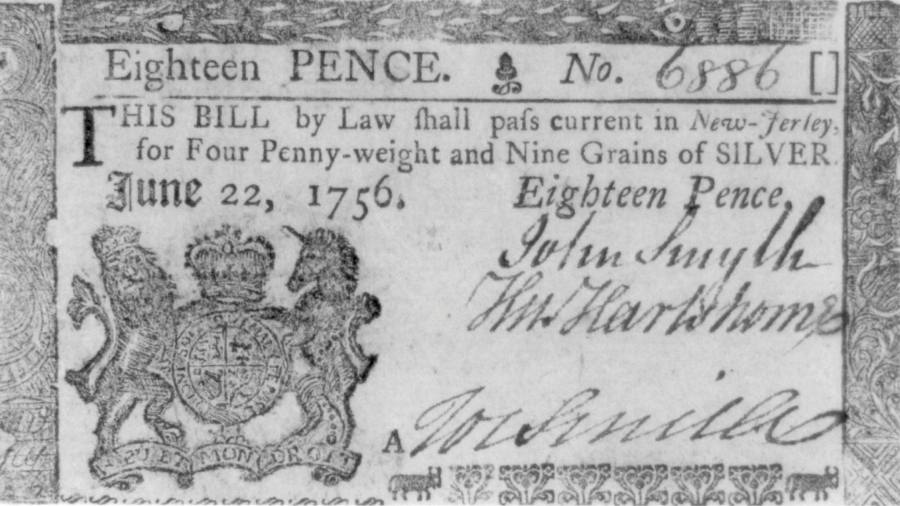

In the 18th century, the American colonies obtained only a small part of the world currency of their time, a flow of hard silver coins that went directly from the Andes to China. The merchants of those colonies did not patiently stack the coins they had and sat down to a deflation. They pushed to change local exchange rates to get more money, and eventually pushed colonial governments to create paper money, colony by colony. Some of these notes on paper collapsed. Some inflated their value, but continued to circulate. Some notes, like the one in Pennsylvania, held their value very well. This role does not seem like tyranny; it seems an adaptation to the circumstances.

There is no true nature of money. Almost everywhere you look, you can find hard coins and credits circulating together. The Habsburg kings of Castile had silver from the Americas, but financed their wars with credit. Renaissance Florence and Venice had gold from Africa, but financed their trade on credit. The merchants of the medieval fairs of the wool of Burgos canceled the commercial debts of each one and liquidated what was of currencies.

And over the past week, the texts of my childhood friends have not focused on bitcoin, but on dogecoin, an expansion of the money supply created as a joke about a dog. People have ways to create the money they want. There has never been a good way to stop them.

[ad_2]

Source link