[ad_1]

Content warning: This article makes references to suicide.

CARTHAGE, Miss.—John Mask leaned against his truck, squinting in the hot sun. It wasn’t the van he’d had in the good old days, he admitted. That was a remnant of the past, another casualty of the years gone by.

Had it really been years? When Mask talked about the early days of coronavirus, they didn’t seem that far off. The pain of it all seems weathered, less raw, but still eminently present just under the surface for him.

John Mask watched his life evaporate in the pandemic. Before COVID-19, he led a small business bearing his name, a construction services company out of Louisville, Miss. Mask and his team worked on residences across the region, installing ceramic showers, tiling roofs.

The pandemic brought it all crashing down. And when he reached out to participate in the programs intended to keep small businesses alive, he and his livelihood slipped through the cracks.

‘One Job at a Time’

John Mask started his construction company in 2017, building a reputation one job at a time.

“I mean, I’m 27 years old,” Mask told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview earlier this year. “I only had half an idea how to run a business. I started with some old used tools I’d accumulated from pawn shops, you know? Just buying little things here and there.”

By the start of 2020, Mask’s business had grown enough to employ a whole team. What started as a one-man operation had become a small community. “It’s not just responsible for my family, my income. It’s seven other men. It’s all their families, too,” Mask said.

Like so many others across the globe, the pandemic hit Mask Construction Services hard. A sudden freeze severed its ongoing contracts as the world ground to a halt. And in the months that followed, the basis for Mask’s entire business model dissipated in paranoia over the infectious disease.

“People weren’t calling,” he said simply. “Everybody was scared.” Mask understands the fear, even though it was catastrophic for his business. “I mean, I wouldn’t want three or four men coming into my house, working around me and my family and possibly exposing us.”

The months dragged on. “That was pretty much all of 2020,” Mask said. At times in the interviews, he still seemed stunned by how quickly it all fell apart—a small, thriving business swallowed up in a pandemic that seemed to stretch on without end.

The businessman saw a silver lining in the distance, however. Congress was pouring billions of dollars into programs to help businesses like his. A loan could help keep Mask Construction Services solvent, a grant or an advance would be even better.

He just had to get one.

COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan

John Mask was humble about the contracts his business completed, but a casual look through dormant social-media pages shows an impressive gallery of professional work: fences and furniture, stonework bathrooms, cabinets and kitchens.

What he was not prepared for was involuntary enrollment into a pandemic-era administrative footrace with unclear rules and limited rewards.

The near-global shutdown led Congress to create the Paycheck Protection Program, part of the CARES Act, diverting billions to small businesses to cover payroll, mortgage, rent and utilities. The program offered a lifeline for businesses frozen out of their natural economic rhythm for up to two months.

Mask applied for the Paycheck Protection Program as soon as he could, but a nationwide surge of demand overwhelmed the program, in spite of its vast sum of available funds. Money ran out a month before the intended program’s end, and countless small businesses found themselves on the losing end of a coin flip—and out thousands of dollars in payroll funds for employees in need.

PPP funding nearly stretched to a trillion dollars, but the implementation and downstream effects of the program were often criticized and, to this day, still poorly understood. For Mask, losing the PPP funds was a punch to the gut, but participation in Renasant Bank’s Renasant Roots program brought a small ray of hope in the form of a $1,500 grant. While the money wasn’t enough to keep his business afloat by any means, Mask looks back on the program and the community bank’s assistance fondly.

“I met a lot of really, really good people,” Mask said of those who at least acknowledged the crisis his business faced.

Undeterred, Mask then applied for the program he hoped could save his business and home life: the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan, or EIDL. The program offered loans to small businesses and other valid institutions, covering up to six months of operating costs. The terms allowed up to a year of deferral on repayment and fixed, low-interest rates. For many, it represented one last opportunity to salvage a struggling business.

Moreover, Mask applied for the Targeted EIDL Advance and Supplemental Targeted Advance, emergency funds of up to $10,000 and $5,000, respectively, that would not need to be repaid. These funds, the SBA explains, are for “the hardest-hit small businesses and nonprofit organizations,” those who could display a massive loss of revenue in the early days of the pandemic. Mask Construction Services qualified.

For John Mask, the approval was the first sign that his business might be able to recover from the hard shock of the early pandemic—that in spite of the hardship, he might be able to weather the storm until some semblance of normalcy returned.

Two years later, he has yet to see a dime.

‘Better Than Nothing’

John Mask provided an exhaustive archive of his correspondence with the Small Business Administration to the Mississippi Free Press. Starting in mid-2020, it contained dozens of desperate emails from Mask seeking clarification on what information was necessary to receive the funds that the agency had already approved.

Again and again, the response he received came in the form of automated messages, repetitive reminders of the basic features of the EIDL program. The back-and-forth messages reference emails and phone calls assuring Mask that help was on the way.

Eventually, Mask received a glimpse of what had gone wrong. An SBA rep, he said, “reached out to me and explained (that) the account I originally had on the application was a closed account.” Somewhere between the initial approval and the delivery of the funds, Mask lost his primary bank account, which had been tied up with his nearly defunct business. He is certain that he attempted to update the information, but found later that the agency had retained his updated routing number and kept the old account number.

That mistake, whether it was an error on Mask’s part or introduced due to some element of an SBA system, appears to have permanently derailed the vital assistance he needed to save his business.

Bryn Bagwell, director of lending for Communities Unlimited, a certified development finance institute based in Arkansas, watched the tidal wave of demand crush the usual systems that small businesses depended upon as the pandemic unfolded.

“These were deadlines … that made everybody go crazy to be signed on. Because they were going to run out of money. And so you’ve got a huge volume of demand and a system that has not been completely developed yet,” Bagwell said, here referring to the PPP program.

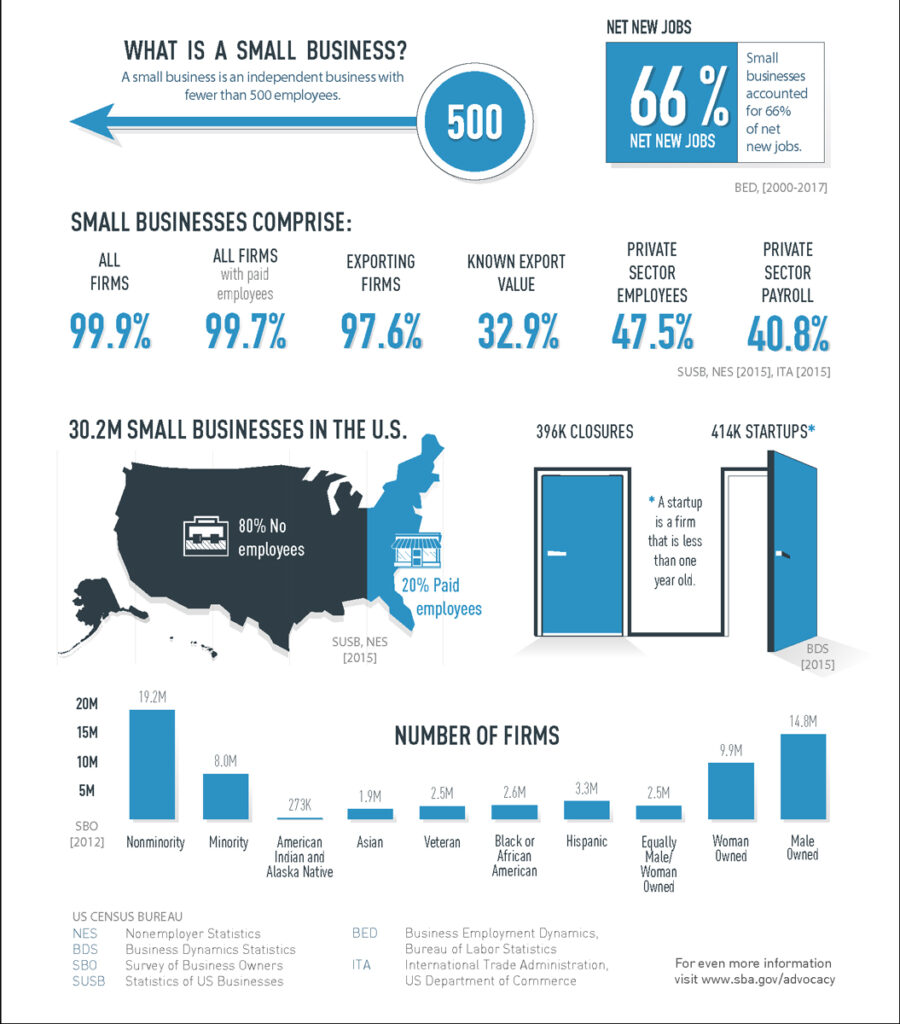

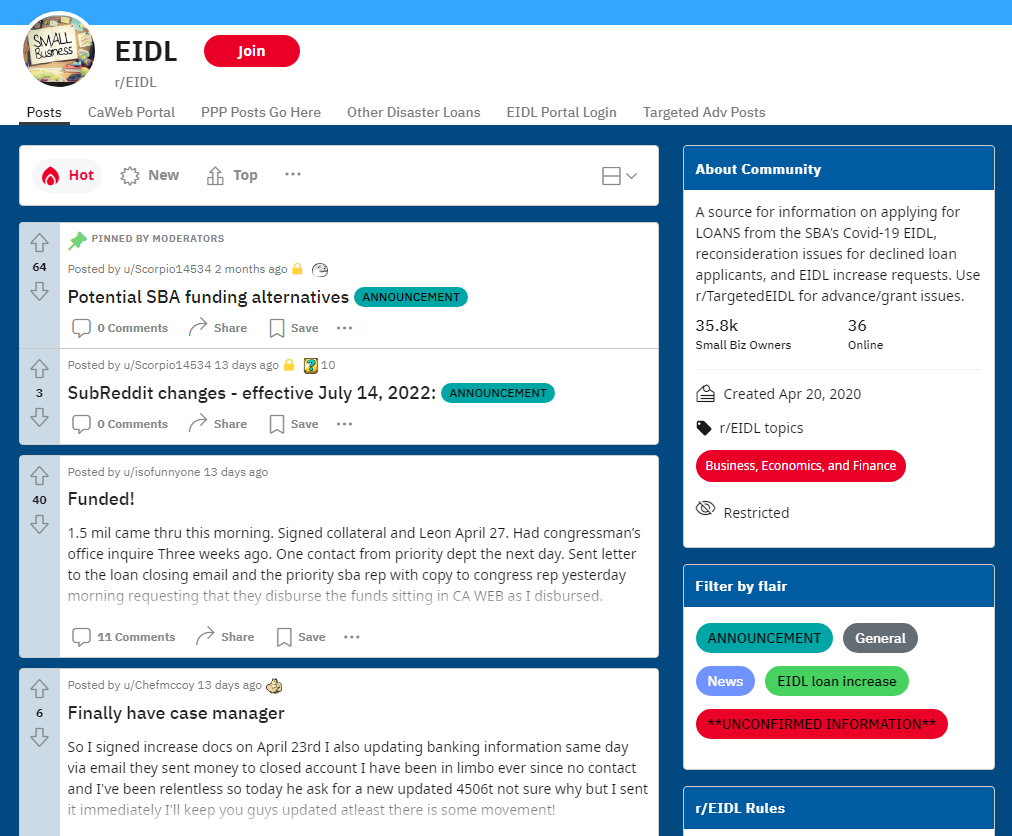

Around Mask, the pandemic crushed small businesses in a vise, temporarily evaporating entire sectors of the economy. Data from the period show the subtraction of 3.3 million small business owners from the U.S. economy between February and April of 2020.

A powerful rebound followed, with some sectors recovering their numbers rapidly. But a replenishment of the head counts of small-business owners alone does not prove a full recovery of the companies themselves.

Pre-existing small businesses during the pandemic were by and large not equipped to deal with a global catastrophe on the scale of COVID-19. A survey of more than 5,000 small businesses from researchers at the University of Chicago and Harvard University found that “median businesses with more than $10,000 in monthly expenses had only about two weeks of cash on hand at the time of the survey.”

Mask found himself in a similar situation as the pandemic arrived, making it month to month but lacking the deep cash reserves to take an unplanned vacation with no definite end. Weeks unfolded into months, desperation sinking into despair. His financial situation and family life began to disintegrate. Through all of it, Mask found the opacity of the program ruinous to his mental health.

“I qualified for it,” he said. “I applied for it. Why won’t y’all help me? Why won’t you give me an answer? If they’d have just said, well, ‘screw you, you’re not getting paid.’ I mean, at least I could process that. I’d know. I’m not going to get this money. I’m not going to get any help. That’s better than, you know….”

He fumbled to describe his tense aggravation present after so long without answers.

“That’s better than nothing.”

‘The One Thing That Did Not Help’

The experience of waiting for help in a catastrophe was an isolating experience for Mask. But he was by no means alone in his experience with the SBA in general or the EIDL program in particular. William Patrick Butler, a Jackson-based photographer, shares his frustration.

Like Mask, Butler missed out on the earliest pandemic funds for small businesses in pandemic decline. “After they turned down my loan in 2020, I thought that was it,” Butler admitted. “I didn’t check back.”

His situation was not immediately dire, so like many others, Butler muddled through a long and confusing pandemic. He put the thought of federal support for his photography business out of his mind until March 2021 when the SBA emailed him, based on his previous applications, encouraging him to apply for the EIDL program.

The process sped along at first. “I went ahead and did it,” Butler told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview. “In June of 2021 I had been approved for the supplemental targeted advance.”

But he hit a roadblock in July 2021. Butler was using Chime, a mobile service associated with BancorpSouth Bank and Stride Bank. His provider had declined the money as possible fraud. “I was like, how is this fraud? The SBA is a legitimate federal government agency,” Butler said.

Butler scrambled to rectify the issue, updating his information to use a brick-and-mortar bank where he had a secondary account. But by then he was already caught in the same loop that Mask had found himself in.

“I called them at least once a week, to be proactive. At least once a week from August 2021, all I get back is (a message) that ‘we have your info, it’s in the pipeline, please be patient.” It had been a year and a half since Butler’s greatest need. But he kept waiting.

Blair Edwards, owner of The People’s Cup MicroRoastery in Starkville, Miss., was waiting, too. Edwards had the distinct misfortune of having expanded his business to a new location weeks before the global catastrophe of COVID-19. He inked the lease in January 2020.

“We were working on renovations when things started shutting down,” Edwards told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview. “So we decided the smart thing to do was not to pour all of our resources into renovating a building during a pandemic. We didn’t know how long it was going to last or what we would need.”

Countless sales and events flew out the window. Edwards applied for loan assistance as soon as it was a possibility. “I was never told why I was denied, and it took me until December 2020 to actually get denied,” he said. “And that was after a long process of reconsideration.”

In the middle of a long process of clarifying information with a loan officer, Edwards received an abrupt denial letter. “In the middle of all that, I get an email saying I’m denied. Nobody could tell me why, including the customer service line, nor my loan officer. The phone number was useless,” he said.

Edwards marveled at the complete lack of transparency, accountability or efficacy. “(For them) to be the one federal government organization for small businesses in the U.S.,” he said. “I thought this country ran on small businesses. That’s what they say,” he remarked, laughing bitterly.

He reflected on the bracing isolation of running his own business with such little support. “You know how hard it is in this economy to live, let alone try to start a business, let alone find the capital for that. The SBA was the one thing that did not help. At all,” he said.

‘I Am Done with the SBA’

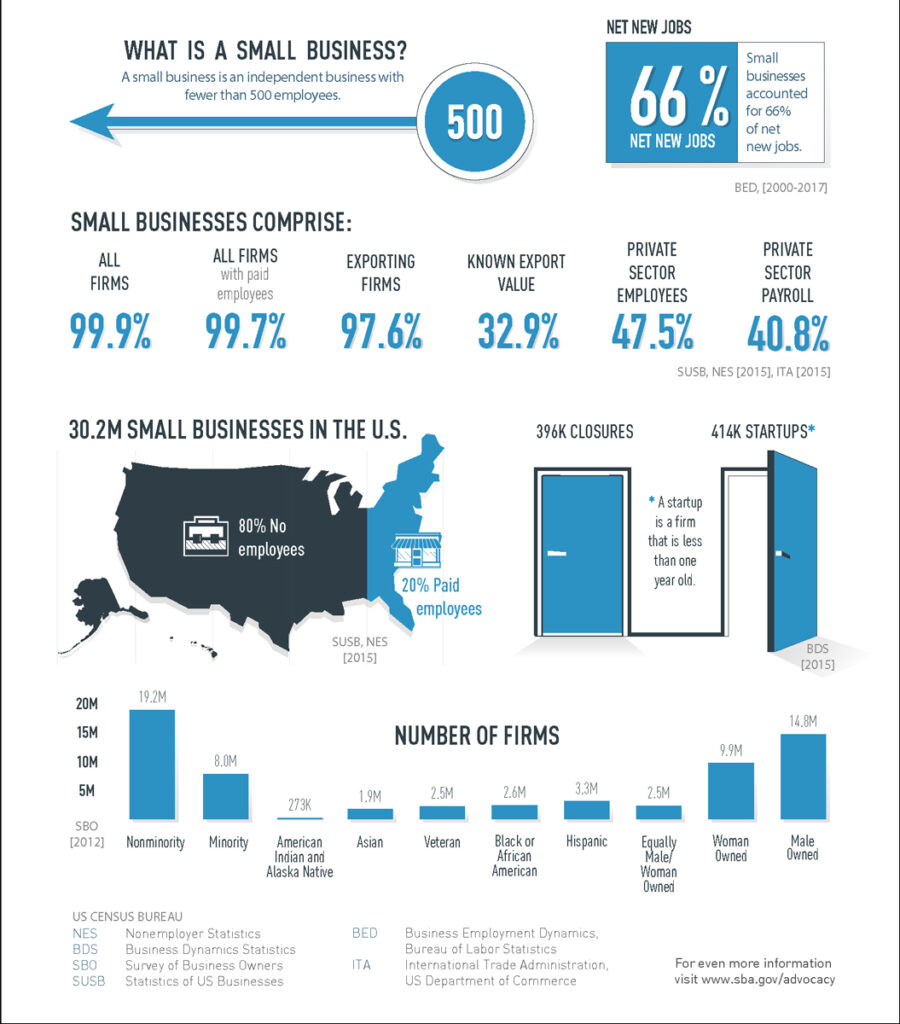

Beyond Mississippians struggling to make sense of an impenetrable bureaucracy, dedicated forums of small business owners have cropped up online, trying to crowdsource answers from a program that seems designed to operate in secret. An EIDL subreddit contains the testimony of thousands of users all struggling in some way with the program. Day by day, stories of successes and agonizing delay trickle in.

“Silly me for thinking the government would help a first-generation American business that was opened with hard work and life savings and no debts,” one user wrote after months of posts on the subject.

“Like most everyone else, I am done with the SBA and the bullshit,” another wrote. “I can’t continue on like this, feeling like there is no light at the end of the tunnel. My business has collapsed, and I’m drowning in debt due to not having income to pay monthly bills. I can’t take (it) anymore and I feel like I’m at the end of my rope.”

Mask went through the same brutal cycle. He checked online catalogs of all the businesses that had received PPP funds, stunned at the breadth of the companies that the program had funded and how much they’d been given, all while his own company languished and his employees dispersed to find new opportunities for themselves.

“There’s a website that lists businesses that have received that funding,” Mask said. “I (could see) all these businesses in my hometown that received that money. You know? Everybody was getting it. Why? Why wasn’t I?”

The pandemic dragged on. Mask spiraled as he lost his business. He credits the collapse in part with the dissolution of his family, and as he lost hope, his thoughts turned to killing himself. “I’m going to be blunt, I’ve attempted suicide,” he said, and more than once. “We don’t talk about mental health here. And there’s not enough resources (for people on the edge),” he added.

Mask said stoic male culture had not equipped him to work through the deepening burden before it came to a head. “Men especially, you know, we’re told ‘keep it to yourself,’ and ‘keep your chin up,’” he said.

He doesn’t blame the SBA or the EIDL program for the chaos that entered his life. But that was his only resource—the program and the people he turned to in long years of turmoil. The silence, misdirection and confusion he received left him feeling all the more isolated.

Multiple Attempts For SBA Interviews

Over the course of several months in late 2021 and early 2022, the Mississippi Free Press reached out to the Small Business Administration for interviews on the EIDL program and the targeted advances with two major lines of inquiry. First, what could interested parties do to clarify where their applications were in the intricate process of acceptance, reconsideration and funds disbursement? Could people like Mask, Butler and Edwards have done anything differently to receive their money earlier? What could they do now?

Second, how had the process, which was intended to address the economic shock of the pandemic’s sudden onset, dragged out into an unresolved frustration for so many small-business owners? Years later, why were so many who had been approved early left to languish for so long? Had the agency been starved of resources in a time when it needed more support? Had technical failings in the constellation of financial systems needed to deliver the critical support prevented their delivery?

In these attempts this reporter experienced small parts of the opacity and frustration that the small-business owners interviewed for this story experienced. The SBA variously ignored or declined most attempts at contact, and occasionally promised longer conversations on the topic that rarely materialized.

Perhaps the most important insight into the difficulty many had in finding answers was that the closest offices of the SBA—like those in Mississippi itself—were largely uninvolved in the EIDL program, unable to offer serious insight into the workings of the system. The Mississippi SBA, at least, was prompt with its responses.

Janita R. Stewart, district director of the SBA’s Mississippi district office, returned a request for an interview on the topic with a pair of emailed statements.

“The SBA’s COVID EIDL program is managed by the SBA’s Office of Capital Access (OCA), HQ in Washington, DC,” Stewart wrote. “SBA district offices like the SBA Mississippi District Office and all others throughout the country, merely serve as a support system to OCA for this particular program.”

The Mississippi Free Press pushed for more information. For the countless Mississippians still muddling through the obscure process, was there no more clarity available? Stewart again declined an interview.

“Unfortunately, we do not have any further information to share or provide at this time concerning COVID EIDL applicants that have applications remaining in the system awaiting to be finalized,” she wrote. “Our district office, as is the case with other district offices throughout the country, continues to provide only backup support to the Office of Capital Access in HQ which manages and administers this program.”

This reporter then reached out directly to the Office of Capital Access, requesting an interview with anyone from this central branch of the SBA capable of answering the same questions. After several attempts via phone calls and emails, Lola Kress, regional communications director at the SBA, told the Mississippi Free Press that an interview was “not possible at this time.”

Kress did respond to some of the MFP’s questions—which the Mississippi Free Press allowed to be emailed despite our person-only interview policy in order to get answers for desperate business owners—with a brief statement from “a team” in the SBA’s press office. This reporter asked how many backlogged requests the SBA faced on a day-to-day basis. “This changes each day as requests for increases, reconsideration, and appeals come in each day,” the statement read, “but in general the inventory continues to be managed in a way to avoid any backlog. There has been no backlog since the summer of 2021 where it was closed out.”

When this reporter shared that information with Mask, he was astounded. Both in his own personal experience and in the testimony of many on forums like r/EIDL, stories of staggeringly long delays and reconsiderations abound, even now in mid-2022.

Seeking additional clarification, the Mississippi Free Press reached out yet again, attempting to find someone at some level of the SBA’s broad hierarchy who could speak openly on the program. Eventually, on March 21, 2022, Rhonda Fisher, supervisory lender relations specialist, responded to a request for contact with a hopeful message indicating that someone might be reaching out soon.

“I just wanted to reach out to you this morning to let you know that we are attempting to put you in touch with a representative to discuss COVID EIDL and will let you know once we have the contact,” Fisher wrote.

The Mississippi Free Press never received that call.

A Flawed Design

Bryn Bagwell told the Mississippi Free Press that the role of Communities Unlimited has always been to address the needs of businesses that usually would not qualify for bank loans. During the pandemic, that role included engaging with many business owners who were struggling to secure SBA loans and advances.

“We had to be very responsive to our existing borrowers,” Bagwell said. “Once the pandemic hit, it slowed down their ability to provide products and services. We provided grace (periods) with payments, modifications of their loan terms, and quick turnaround loans.” These “reboot” loans, she said, helped kickstart businesses that had otherwise completely sputtered out during the pandemic freeze.

Communities Unlimited also served as an SBA microlender. That role—addressing the modest but still significant needs of truly small businesses—was critical for many. “You’ll see a lot of the larger banks talk about how many dollars they got out. We like to talk about how many businesses we helped,” Bagwell said.

Sometimes the loan is small. “I think our smallest loan was $790,” she recalled. “There is no bank who would put forth all the time and effort to get a small business that size of a loan. But it mattered to that small business.”

Bagwell has sympathy for the SBA, beleaguered by a tsunami of extreme need unlike anything it had ever faced before. But she also encountered countless stories of the glacial gridlock facing small operators like Mask, Edwards and Butler.

“The process was cumbersome,” Bagwell said. “The SBA was not equipped with the technology to handle this big lift of applications for a brand new program that had (these) requirements. They just weren’t. So they did the best they could.”

The crush that had hit all of the businesses was washing over the SBA, too. “They didn’t have the people,” Bagwell added. “Plus, with COVID, they had trouble getting people hired.”

The many delays and denials that plagued the drawn-out process made the SBA the proximate cause of frustration for small business owners on the ground. But Bagwell highlighted the role that Congress played in dumping such an enormous task on the agency.

“The SBA was trying to use a newly designed system—they’d receive instructions and be told ‘we’ll send you more later, these are just temporary.’ And then they’d receive more instructions, and they’d still be temporary,” she said. “Legislators provided very little clarification about what the legislative intent was. (Disbursing billions of funds) just wasn’t as simple as (lawmakers) thought it would be.”

That “newly designed system” is not merely a metaphor, but a constellation of highly technical databases and programs. This patchwork, Bagwell said, was a constant source of confusion, the origin of much of the gridlock that left applicants and their small businesses out of the loop.

When the SBA first made PPP money available to the public, their systems cratered from the overwhelming demand, locking even banking institutions out of the program for days. Even when the system came back online, Bagwell admitted, often the process was so labyrinthine that different parts of the agency could have diametrically opposite information for lenders and borrowers.

“We were discouraged at the end of the PPP program because, apparently, they ran out of money without telling us that they did. So we were going in every hour, every two hours, checking on the applications that we had without decisions,” Bagwell said.

“For one month, we checked and checked and we called and we emailed, trying to find out why the applications had not been decisioned. Finally, after 30 days, they said ‘we ran out of money.’ We asked how they couldn’t have known that. Why keep telling us we’re working on it for 30 days?” Bagwell asked.

“There’s two different systems, not talking to each other, all trying to tabulate a big volume toward the end of the funds. They ran out of funds before the actual deadline to apply. We didn’t know it. Nobody knew it,” she said.

The borrowers who had been desperately waiting for the funds were left in the cold. “We had these borrowers who we effectively lied to for one month because the SBA … had erroneous information,” Bagwell concluded. Communities Unlimited ensured that the borrowers in question received extremely low-interest loans.

Confounding moments like this continued even for organizations, themselves lenders, who were expertly equipped to navigate the complex realm of federal loans and financial systems. For individuals seeking EIDL loans and advances without the assistance of professionals like Bagwell, the process was entirely opaque.

‘Who’s Holding These People Accountable?’

None of the interview subjects seemed the least bit surprised when this reporter shared the flimsy results of attempts to request clarity from the SBA. Contradictions or outright silence, they agreed, were the usual results of attempts to discuss the subject with the agency at all levels.

“What is so frustrating is that you can’t even find out where you are in the process,” Edwards said. “So the burden is on you to repeatedly check and check and check and check.”

Even in his frustration, Butler expressed empathy for the ground-level employees and call-center workers who had to field so many requests for information.

One shared experience united Butler, Mask and Edwards, and indeed many of the other small business owners who continue to struggle with the process. Somewhere between application and final delivery of the funds, some singular error seemed to warp the entire system. What should have been minor clerical mixups, either on the part of the likely overworked SBA staff, subcontractors, or from the applicants themselves, led not to weeks of delays, but often years.

But the name of the program is the Economic Injury Disaster Loan, specifically intended to deal with mass disruption, Butler said. “If you are in a disaster,” Butler asked, “should one mix-up be enough to collapse the entire goddamn system?”

‘Not All People Are Lucky Like Me’

Eventually, Butler and Edwards saw movement on their applications, possibly on track to see some benefit, even if it came years after the onset of the pandemic. Butler received his funding in 2022, and he’s glad to be done with it. Above all else, he is grateful for the privilege and support that kept him afloat before it arrived.

“I’m lucky,” Butler said. “But not all people are lucky like me. People have real life needs every single day. Not wants, needs. And they have to deal with this for a year or a year and a half or whatnot. I feel for them. The entire system just completely rolled over them.”

Edwards was not so lucky. After nearly two full years of contradictions and scattered communication, he received his final denial for the EIDL loan on March 14, 2022. The final denial, Edwards said, was based on a loan officer’s inability to locate his 2018 tax returns, something Edwards says he actively has in his possession.

But he’s done fighting with the agency.

“Luckily,” he said, “I started exploring some other options.” That’s when he found Communities Unlimited. He got the loan his business needed, and credits the organization with helping him stay afloat. “I’m actually glad that I got that instead. The rate is a little bit lower, and it comes with a whole financial team. Their job is actually to help.”

Edwards, armed with tenacity and meaningful financial support, is finally back on track. The People’s Cup is opening at last. “Our grand opening is going to be in September,” he said, voice buoyant. It was a brief, strange delay: only two years and some change.

He knows how easily things could have gone the other way. Many are coming through the late pandemic years having lost much.

Mask is one of those people. He has given up trying to protest the denials, to struggle through a system that was supposed to prop up a now dead business. When the Mississippi Free Press first spoke with him in 2021, he wanted answers and a resolution to his application. Now he seems hungry for at least accountability.

And he wants his story told. From the depths of misery, Mask says he’s endured. He wants others to know that they are not alone, and that they can find help even if it seems inaccessible at times.

“I went and I got myself into therapy, which is not something I wanted to do. My idea of what therapy was was completely off,” he admits. “I thought, ‘how are you going to tell me what’s going on with me better than I can tell myself?’”

But after coming so close to taking his own life, Mask said, he relented, and found the experience to be far more meaningful than he’d imagined. “But what it actually did is it allowed me to vent, to talk it out. It gave me different perspectives, it allowed me to work through it myself.”

Now, Mask said, he’s putting his life back together. He’s gone back into business with a close friend. His headspace is much healthier. But he knows that disaster will come again, if not for him then for someone else, somewhere in the nation.

“It’s just that there are no answers,” Mask admitted. “Who’s holding these people accountable? I’m sure if this has happened to me, I can only imagine the others. People who must be in even worse circumstances.”

[ad_2]

Source link