[ad_1]

A lot of Twentieth Century popular culture—books, movies and television shows —is cringe-inducing: comedy routines that ridicule minorities and people with disabilities, women portrayed as foolish sex objects, and clever white men prevailing over ignorant, violent foreigners. The humor falls flat, the stories are predictable, and we realize how their messages contributed to racism, sexism, and bullying.

Some old transportation planning practices are similarly cringe-inducing. They assumed that virtually everyone (or at least everyone who matters) desires an automobile-dependent, suburban lifestyle, so governments have an obligation to provide roads and businesses to provide parking facilities for their use. They assumed that transportation means driving, transportation problem means an impediment to driving, and transportation improvement is anything that makes driving faster and cheaper. These assumptions are still reflected in many planning practices: travel surveys that undercount non-auto travel; traffic models that predict ever-growing automobile demand and “gridlock” if roads are not expanded; automobile-oriented performance indicators such as roadway level-of-service and congestion delay; and dedicated funding that can only be used for highways.

These practices are classist and racist. They favor faster but expensive modes over slower but more affordable and inclusive modes, and they allowed vibrant but lower-income urban neighborhoods, which highway planners described as “blight,” to be destroyed to benefit suburban motorists. We now recognize that these practices are harmful and unfair. Most practitioners that I work with strive to apply more comprehensive and multimodal planning.

I was therefore surprised, disappointed, and a little amused by Steven Polzin’s recent Planetizen blog, Induced Travel Demand Induces Media Attention, which reflects old-school planning. He argues that highway expansions face unjustified criticism and we should not question the importance of highway building. It’s the tired old shtick: Automobile travel is good! Traffic congestion is terrible! Non-auto modes are irrelevant! We need bigger highways! Ignore anybody who suggests otherwise.

Polzin claims that everybody benefits from roadway expansions and the additional vehicle travel they induce. Abundant research suggests otherwise. A growing body of evidence indicates that most urban highway expansions are economically inefficient and unfair. Their costs exceed their benefits and they contract community goals. Other solutions are usually better overall.

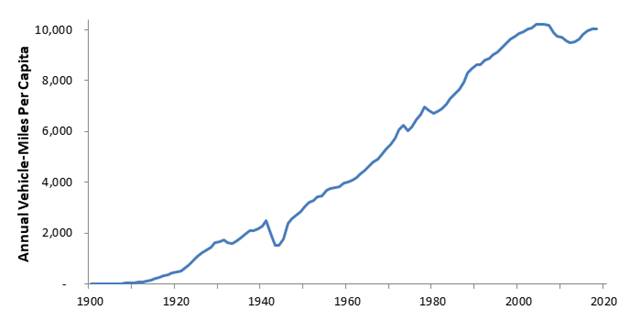

Polzin misrepresents the debate. He claims that highway expansion critics ignore growing travel demands. No, we don’t ignore them, but we place them in a larger context. After a century of growth, per capita vehicle travel peaked about 2005, as illustrated below, and current demographic and economic trends are increasing non-auto travel demands. We should respond to these changes by creating more diverse, affordable and efficient transportation options.

Vehicle Travel Trends

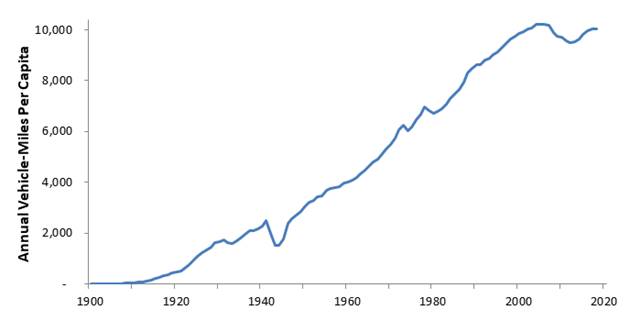

The old-timers haven’t learned. Compare what actually happened with what was predicted, as illustrated below. Their models simply extrapolate past trends into the future, and so conclude that cities will face gridlock and highway expansions are essential. They were wrong. In fact, vehicle use did not grow as predicted and cities never experience gridlock. In fact, traffic congestion tends to maintain equilibrium, and it increases to the point that delays discourage some potential but low-value peak-period vehicle trips. As a result, traffic congestion is to motorists what the tide is to sailors: a predictable factor to consider when making travel decisions.

This is important because transportation planning can be self-fulfilling: if planners predict that vehicle traffic will grow agencies will invest in more roads and mandate more parking, resulting in more vehicle travel and sprawl. However, if we recognize growing non-auto travel demands and invest more in walking, bicycling and public transport people will drive less, rely more on non-auto modes, and choose more compact, multimodal neighborhoods.

Polzin argues,

Overplaying induced demand arguments as a pretext for discouraging roadway expansion or presuming travel demand can be accommodated by investing in alternative modes can be disingenuous and ill-informed. The presumption that directing resources to transit, bike, or pedestrian options can meet the mobility needs of all people and goods seldom works out as a real solution that is financially sustainable, environmentally superior, or offers comparable mobility, accessibility, or other benefits.

This is typical highway advocate hyperbole. I agree that no mode can serve all travelers, so transit, bikes, and walking can’t meet all mobility needs, but neither can automobiles. Just because some trips are best made by automobile does not mean that all trips should be made by automobile or that roadway expansions are cost-effective. Improving non-auto travel conditions benefits current and future users of those modes, and benefits motorists by reducing their traffic and parking congestion, and their chauffeuring burdens. Highway expansions do not.

Although few motorists want to forego driving altogether, surveys indicate that many would prefer to drive less, rely more on non-auto modes, and live in more walkable neighborhoods, provided that they are convenient, comfortable, and affordable. More rational planning invests in non-auto modes first, and only expands roadways if motorists are willing to pay the cost through tolls.

I don’t mean to pick on Steve alone. He is part of a cadre of mostly middle-aged men who promote highway building. Another example is the Texas Transportation Institute’s Urban Mobility Report, which also perpetuates the idea that traffic congestion is a terrible problem and that urban highway expansions are a good solution. These old-timers dismiss the implications of induced travel. Let’s see what this means.

More Comprehensive Analysis

An abundance of research demonstrates that within a few years, the majority of expanded urban highway capacity fills with generated traffic (additional peak-period vehicle trips), and induces additional vehicle travel (total increase in vehicle miles traveled). This has the following impacts:

- It reduces predicted benefits. Contrary to what proponents often claim, urban roadway expansions do little to reduce congestion. In most cases, within a few years, traffic speeds decline to previous levels with greater total volume resulting in more downstream congestion. For example, expanding an urban freeway often increases surface street traffic volumes and congestion problems. It is therefore dishonest to sell highway expansions as a solution to congestion.

- The additional vehicle travel increases external costs. Induced vehicle travel increases total parking problems, crashes, pollution emissions, and sprawl-related costs. This is inefficient and unfair. For example, by inducing more vehicle travel on surface streets, roadway expansions increase the pedestrian delay, crash risk, traffic noise and air pollution that automobile traffic imposes on urban neighborhoods.

- User benefits are small, consisting of the additional peak-period vehicle miles that users will only take if their time and money costs marginally decline.

This is not to deny that roadway expansions provide benefits, but those benefits are different and much smaller than proponents claim. They consist primarily of some households being able to choose more distant suburban homes than would otherwise be feasible, and those benefits are generally offset by increased external costs. As a result, we incur $10 in costs to provide $1 in benefits. Too often, transportation agencies overlook or undervalue these impacts, which overvalues urban highway expansions and undervalues alternative congestion reduction strategies such as improvements to space-efficient modes and TDM incentives. When all factors are considered, urban highway expansions are seldom economically justified.

As discussed in my Planetizen blog, “The Roadway Expansion Paradox” motorists want expensive roadway expansions provided that somebody else foots the bill, but if required to pay directly through tolls, the need for more capacity usually disappears. Such projects waste money, and by inducing more vehicle travel and stimulating sprawl they contradict other community goals.

There are smarter ways to reduce traffic congestion. Any corridor that has enough travel demand to create congestion has enough demand to justify frequent public transit services. There is a strong business case for more multimodal transportation planning. Cities ranging from Boulder, Colorado, Seattle, Washington, Fairfax County and Minneapolis-St. Paul all demonstrate that given better travel options and modest TDM incentives, travellers will shift from driving to resource-efficient modes. Anybody who claims otherwise is unfamiliar with the research or simply lacks imagination.

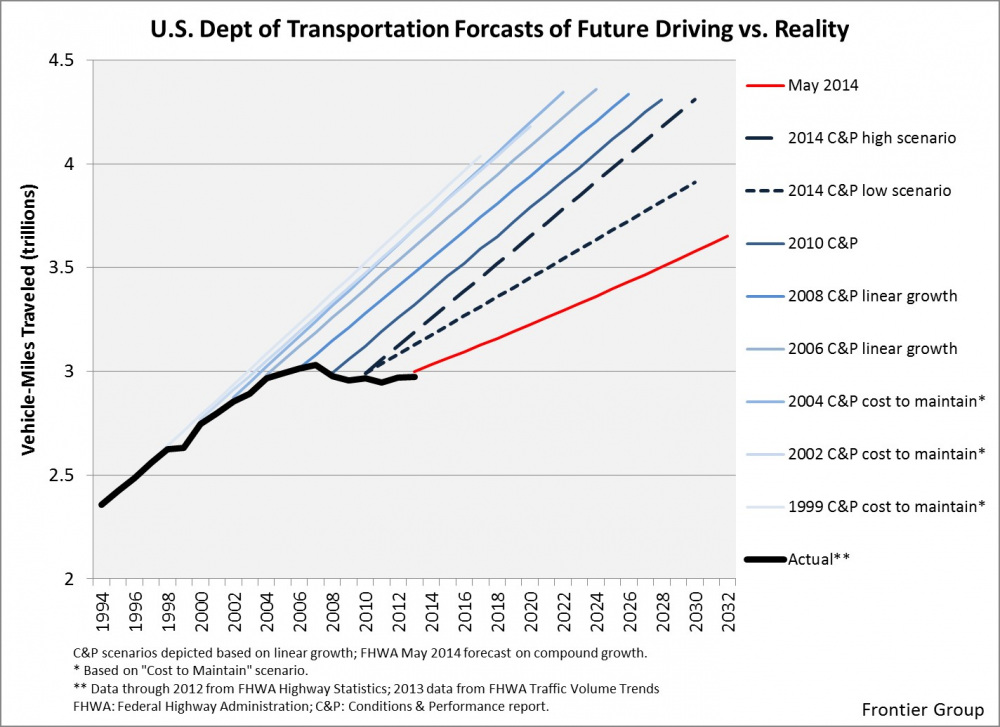

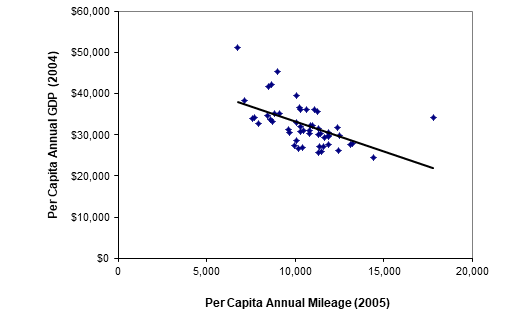

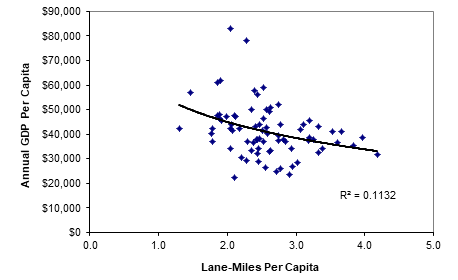

Polzin makes disproven claims. He states, “Mobility is widely recognized as critical to economic competitiveness, productivity, upward mobility, and quality of life.” Wrong, wrong, wrong and wrong. Accessibility, not mobility, helps achieve those goals, and automobile-dependent sprawl reduces them. There is a negative relationship between VMT and roadway supply, and economic productivity, as illustrated below; there is also a negative relationship between sprawl and economic mobility; and I don’t know anybody who considers wider roads with more and faster vehicle traffic in their neighborhood to enhance their quality of life. Automobile-oriented planning and the sprawl it produces are particularly harmful to anybody who cannot drive or is forced to spend more than they can afford on motor vehicles.

Per Capita GDP and VMT For U.S. States

Per Capita GDP and Road Lane-Miles

More Efficient and Equitable Transportation Planning

Most experts recommend a shift from mobility-based to accessibility-based planning and more comprehensive project evaluations that account for additional goals and impacts. This type of planning recognizes the ways that automobile-oriented planning reduces other forms of access, for example, by degrading walking and bicycling conditions and causing more sprawled development, and how this contradicts community goals such as affordability, economic opportunity, health and safety, and environmental protection.

The new paradigm inverts older planning practices. Rather than striving to maximize roadway Level of Service (LOS), which justified roadway expansions and encouraged sprawl, we now strive to minimize vehicle miles of travel (VMT), which justifies shifting investments from roadway expansions to improving non-auto modes.

A growing number of jurisdictions, including California, Colorado, Minnesota, and Washington states, are applying the new paradigm by establishing vehicle travel reduction targets and evaluating transportation projects based on whether they support or contradict those targets. In Wales, dozens of road-building projects were amended or halted after a review showed that they would induce additional vehicle travel. This is bad news for the old highway advocates but great news for multimodal planners.

Steve, you need fresh material! Don’t blame the news media for reporting on induced travel impacts and costs; they are just doing their job. Your audience is tired of the old pro-highway shtick; they want informative and inspirational stories about efficient and equitable transportation planning.

For More Information

Caltrans (2020), Transportation Analysis Framework: Induced Travel Analysis, California Department of Transportation.

Elizabeth Deakin, et al. (2020), Calculating and Forecasting Induced Vehicle Miles of Travel Resulting from Highway Projects, California Department of Transportation.

Susan Handy (2015), Increasing Highway Capacity Unlikely to Relieve Traffic Congestion, National Center for Sustainable Transportation.

Induced Travel Calculator, by the University of California Davis National Center for Sustainable Transportation, estimates the additional annual vehicle miles of travel (VMT) induced by state highway expansions.

ITF (2021), Reversing Car Dependency, International Transport Forum.

Nicholas J. Klein, et al. (2022), “Spreading the Gospel of Induced Demand,” Transfer Magazine, Issue 9.

Amy E. Lee and Susan L. Handy (2018), “Leaving Level-Of-Service Behind: The Implications of a Shift to VMT Impact Metrics,” Research in Transportation Business & Management, Vo. 29, pp. 14-25 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2018.02.003).

Todd Litman (2001), “Generated Traffic: Implications for Transport Planning,” ITE Journal, Vo. 71/4, Institute of Transportation Engineers, pp. 38-47.

Todd Litman (2019), Smart Congestion Relief: Comprehensive Analysis of Traffic Congestion Costs and Congestion Reduction Benefits, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

David Metz (2021), “Economic Benefits of Road Widening: Discrepancy Between Outturn and Forecast,” Transportation Research Part A, Vo. 147, pp. 312-319.

SHIFT (State Highway Induced Frequency of Travel) Calculator, developed by the Rocky Mountain Institute, estimates long-run (i.e., after 5 to 10 years) induced vehicle travel and emissions impacts from highway expansions in U.S. urban regions.

Eric Sundquist (2020), California Highway Projects Face Review for Induced Travel, State Smart Transportation Initiative.

[ad_2]

Source link