[ad_1]

Cracking down on companies that antitrust regulators deem too dominant can be costly and negatively impact innovation and consumer safety. As economists and policymakers in the United States and Europe debate whether to break up big tech companies, they should consider the lessons learned from the 1984 AT&T case, write Monica Schnitzer and Martin Watzinger.

The concentration of market power among Big Tech companies has sparked a heated debate on both sides of the Atlantic. While some see it as a result of the creative power of these companies, others worry about the impact on innovation and consumer choice. The US House Antitrust Committee has expressed concern that these monopolies lead to “less innovation, fewer choices for consumers, and a weakening of democracy.” Among other anti-competitive behaviors, Big Tech companies are said to exploit their dominance in a single market by leveraging unrelated lines of business. Such exclusionary strategies protect incumbents from competition, foreclose markets, and discourage potential entrants from innovating. To address these antitrust issues, the Committee recommends a “Structural Segregation and Trade Restrictions Line”.

In theory, it makes sense to use structural remedies to prevent exclusionary practices, for example, when a vertically integrated firm uses control over an upstream “essential institution” (or “bottleneck” or “natural monopoly”) to exclude competitors in a downstream market. . However, there is little empirical evidence on the benefits and harms of breaking up dominant firms. This is unfortunate, as segregation is costly and should only be implemented if the benefits are substantial and cannot be achieved through more costly means. That is why competition law often focuses on regulatory measures and regulations, such as the Digital Markets Act in the EU, which prohibits gatekeeper platforms from certain practices and requires them to follow certain behaviors.

In recent research, we have analyzed the impact of the breakup of the AT&T Group in 1984, as well as the Bell System, on innovation. The case is particularly informative because the Bell System was home to one of the most productive industrial laboratories of all time, Bell Laboratories, and its breakup had the potential to significantly undermine American innovation. Bell Labs is credited with such great inventions as cellular telephone technology, the transistor, the solar cell, the communications satellite, and the Unix operating system. Bell Labs researchers have received nine Nobel Prizes and four Turing Prizes for their work.

Before the breakup, Bell Systems was a vertically integrated telecommunications company with AT&T as a holding company. It had over a million employees and controlled over 85% of all domestic telephone services through Bell operating companies. It had over 85% market share in long distance services through AT&T Long Lines and 82% market share in telephone equipment through Western Electric. As a natural network-based monopoly, AT&T was regulated at the state and federal level. However, despite the decades-old rule, competitors have repeatedly complained that AT&T has used its market power in local phone services to prevent it from gaining access to the market for telephone equipment and long-distance services.

To end the Bell System monopoly, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against AT&T in 1974, alleging that it was a monopoly. Bell’s operating companies controlled the local telephone networks, which were an essential resource (or bottleneck) for companies that manufactured telephone equipment or provided long-distance services. The DOJ accused Bell of abusing its control over local telephone networks by effectively denying competitors Western Electric and AT&T Long Line access to new customers. Effective January 1, 1984, the case ended with a final decision that kept the Bell operating companies (providing local telephone networks) structurally separate from the rest of the Bell system. The necessary facility rotation was intended to facilitate market access and strengthen competition.

Because of the collapse, Western Electric and AT&T Long Lines could no longer count on Bell’s operating companies as customers. The new free baby bells were and indeed were free to purchase their equipment outside of the bell system. From the point of view of the competitors, the market penetration was now in a realistic state, so they took advantage of the opportunity.

Our empirical investigation shows that the collapse of the Bell System had a major impact on innovation in the telecommunications sector in the United States. One concern people had at the time of the dissolution was that Bell’s patents might be damaged, so any positive effects of the dissolution would come from expensive inventions. Indeed, as a result of the breakup, Bell Labs’ patent portfolio has dropped to about 100 patents per year, but the number of key patents—measured, for example, by the number of patents in the top 10% of the most frequently cited patents in their technology—is high. Subdivision and year of registration – did not.

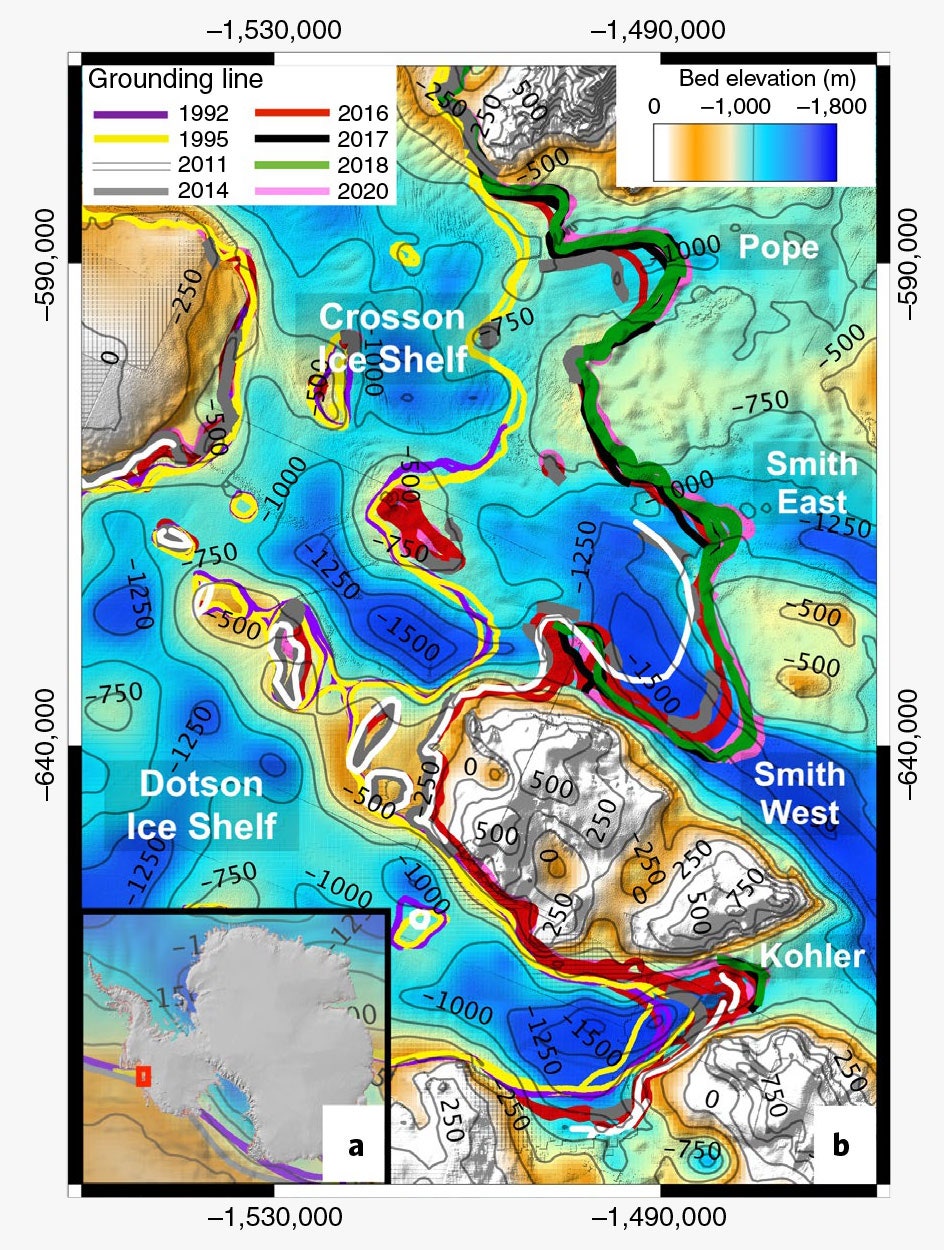

And while Bell’s patents declined somewhat in number after the split, this was more than offset by an explosion of innovation by other companies in telecommunications. Figure 1 compares the total number of patents of US inventors in technology groups in which Bell was active and thus most affected by the infringement (treated groups – solid red line) with the total number of patents in similar but unaffected groups (control groups). – blue line). We subtract the 1981 levels in both groups to adjust for higher overall patenting levels in the treated technology groups. Before 1982, the total patents of both groups follow a very similar trend. Once the separation is declared, the two lines begin to separate. The number of patents infringed in the sector is 19% higher than that of comparable patents in other sectors. That means 1000 more patents per year, about 2.6% of all US patents granted by US inventors in the years since 1982. 20%

The separation not only increased the amount of creativity but also the variety. In the technological fields affected by the collapse, we found a proportional increase in the number of different technological approaches investigated. Moreover, based on textual analysis of patent and patent citations, we find that the direction of innovation has shifted from Bell to new ideas.

Both the general increase in patent applications and the trend change indicate that the period prior to the breakup was lacking in inventions. This observation is consistent with the well-known substitution effect: an incumbent is reluctant to invent products that might replace or disrupt the existing business model.

Anecdotal evidence of Bell’s missing inventions supports this interpretation. As a monopolist, Bell had little incentive to increase product diversity: Seven decades after Bell invented the telephone, AT&T offered its telephones in colors other than black. Company documents indicate that Bell management deliberately withheld an answering machine developed by Bell Laboratories from the public in 1934. Even though many of the underlying technologies were developed by Bell, it is surprising that Finnish consumers had access to mobile phones two years earlier than US consumers. The mobile phone was introduced to the US market after the split.

Could Bell’s collapse serve as a model for today’s antitrust issues? It was intended to isolate the essential utility of local telephone services from the rest of the bell system. This was an attractive structural solution to ensure that Bell could not use an essential facility – local telephone lines – to prevent competitors from successfully entering the market for telecommunications equipment or long-distance services. The question today is whether Big Tech companies control the necessary resources that they can use to exclude competitors in related markets. If competitors are ready to enter these markets after the exclusionary feature ends—as in the case of the Bell split—our analysis suggests that American innovation may benefit from implementing structural solutions.

[ad_2]

Source link