[ad_1]

For years, Michael Maxson spent more nights in hotels than his own bed, working on speaker systems for the titans of heavy rock on global tours. When Maxson decided to settle down with his wife and their two dogs, they chose the city where stadium rock spectacles took him more often than any other: Las Vegas.

After renting for several years, in 2021 he found a home he wanted to buy in Clark County—a place within easy reach of Vegas’s headline venues yet also quiet, an airy single-story stucco house on Dancing Avenue, which backs onto a 2,000-acre park. He dreamed of waking up each morning to look out across lakes and parkland. “It was a beautiful home,” says Maxson. “I mean, the fact you could see the mountains and the sun set and rise. Man.”

But Maxson’s house hunt was unexpectedly chaotic. House prices in Las Vegas leaped up 25% that year, and the market was awash with cheap mortgages and wolfish investors.

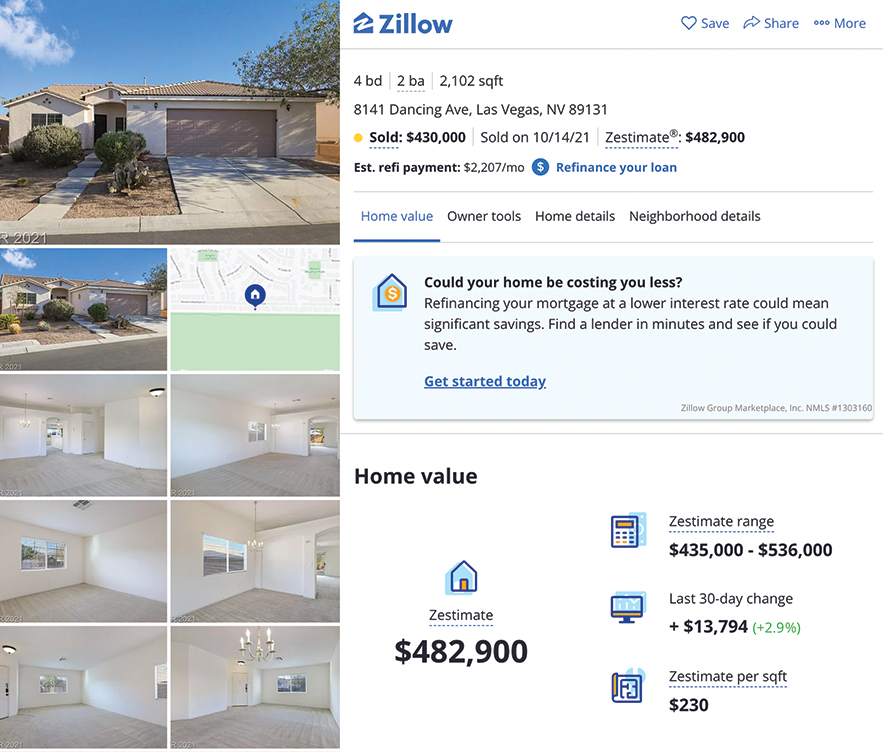

His dream home was not owned by a person but by a tech company. Zillow, the US’s largest real estate listings site, had begun buying up homes in 2018, predicting it could create a “one-click nirvana” for purchasing real estate. It estimated returns of $20 billion a year. Zillow Offers, its “instant buying” business, followed startups like Opendoor and Offerpad, which had pioneered “iBuying,” the so-called “high-tech flipping” model, which uses data systems to price houses and investor cash to buy them before fixing them up and selling them.

In 2021, iBuyers’ purchases jumped to double prepandemic levels, accounting for tens of billions of dollars in home sales. Las Vegas was among the top 10 markets where startups concentrated their investments. In a feverish summer, Maxson had already been outmuscled on two bids by cash offers from Zillow and Opendoor. On Dancing Ave., Zillow now acted as seller, having listed the home on June 24 for $470,000, nearly $60,000 more than it had paid less than two weeks before. But Maxson wanted it and agreed to close at just under asking price.

When he went to take a look at the property, however, he discovered a 37,000-gallon water leak that had eroded garden walls and flooded the neighbors’ yard. Seattle-based Zillow, which owned the home, was oblivious, but the city authorities weren’t—Maxson found a notice stuck to the garage door, threatening a fine for allowing green water to pool, attracting mosquitos carrying West Nile virus. This is one downside of having homes owned by “faceless” corporations, says Maxson: “The [owners] were disconnected from it, because it’s just a number on a spreadsheet.” Though he offered to handle the estimated $30,000 of repairs himself, and take it off Zillow’s books for $30,000 less than the list price, they said no. Maxson discovered soon after that the house had sold to another family, at the same price he had offered. He estimates that he lost about $2,000 on inspections and other costs—the closest he came to securing a home in 22 attempts that summer.

But at the very same time, the startup that had profited from his dream home was discovering cracks in its own foundation. As it turned out, Zillow Offers had lost more than $420 million in three months of erratic house buying and unprofitable sales. As Zillow Offers shut down, analysts questioned whether other iBuyers were at risk or whether the entire tech-driven model is even viable. For the rest of us—neighbors, renters, or prospective buyers—the bigger question remains: Does the arrival of Silicon Valley tech point to a better future for housing or an industry disruption to fear?

Dogfight

By summer 2021, the US housing market had almost run out of records to break. The Washington Post reported house prices at all-time highs (with a median of $386,000 in June) as the number of homes listed hit record lows (1.38 million nationwide). The average home sold in 15 days that summer—half the time taken a year earlier—as cash-rich investors and second-home buyers bought more than ever before. By November, a New York Times headline asked: “Will Real Estate Ever Be Normal Again?”

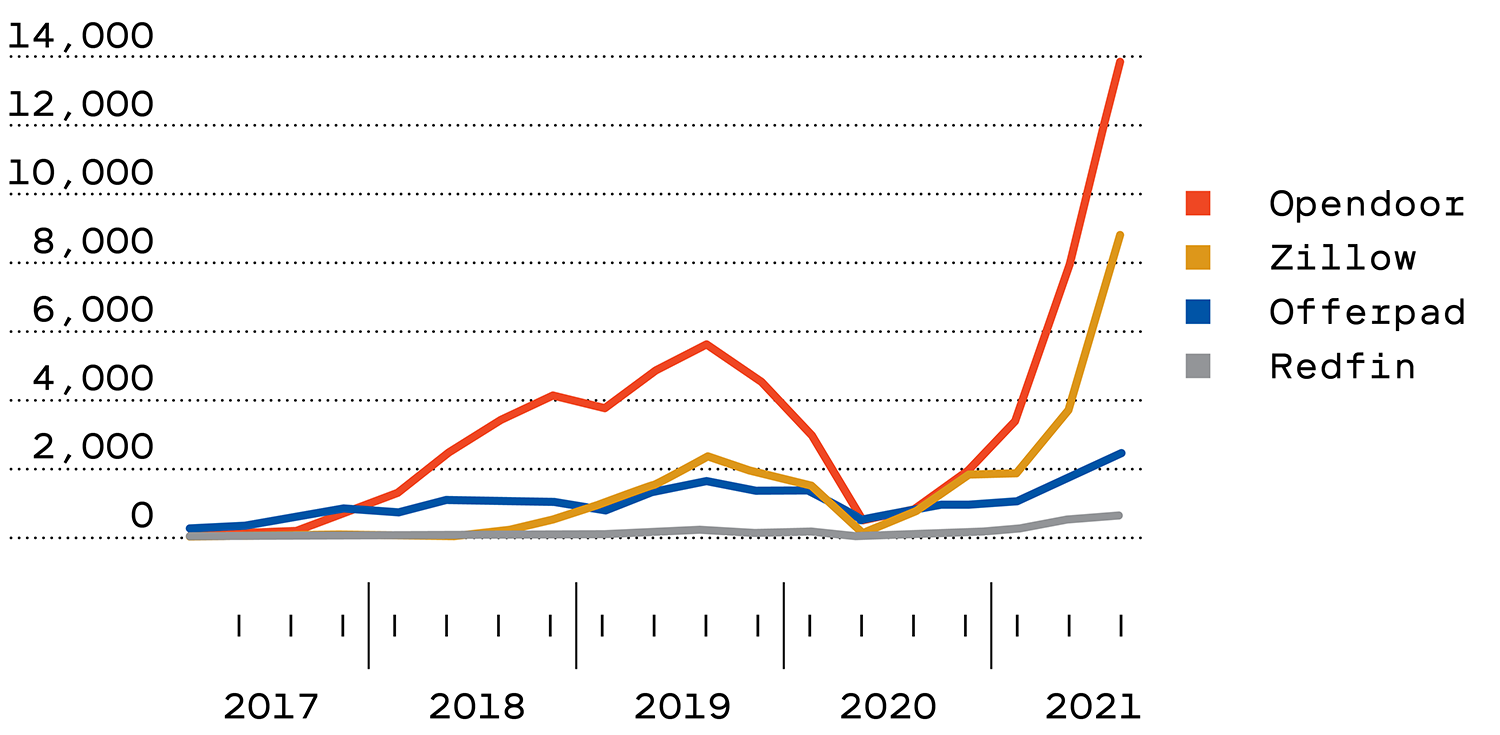

Despite making just under 2% of home purchases nationwide during this period, iBuyers began to play a larger, and more unpredictable, role than most, leading to calls from city leaders in Los Angeles to ban the platforms. iBuyers grow city by city; investment is tightly concentrated in a handful of locations across the Sun Belt, where the top five—Phoenix, Atlanta, Dallas, Charlotte, and Houston—accounted for more than half the total activity. Through 2021, iBuyers bought 70,400 houses nationwide. Nascent iBuyers are raising fundraising rounds in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Canada—but all are looking to the successes and failures of the stateside front-runners.

These cities form a neat growth pattern, following a “strikingly similar” trend to one seen in the trailblazer, Phoenix, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which analyzed iBuying by Zillow, Opendoor, Knock, Redfin, and Offerpad between 2013 and 2018. iBuyers had roughly 1% market share in Phoenix in 2015, growing to 6% in 2018. In the frantic summer of 2021, iBuyers accounted for 10% of home buys in Phoenix. “In certain neighborhoods, 25 to 30% of current listings right now are owned by iBuyers,” says real estate tech strategist Mike DelPrete.

Today Opendoor, the market leader, is operating in 44 markets. iBuyers are intervening in super-hot housing markets by harnessing big data and artificial intelligence to create a one-sided advantage over regular folks. Where house buying was once a “dogfight” between individuals, “now we’re in the age of guided missiles,” says DelPrete, with data-driven buyers claiming a big edge.

Real estate tech startups started digitizing processes that have “been pen-and-paper for centuries.”

Zach Aarons

There is, obviously, a lot of money tied up in real estate. Residential real estate remains the main asset that American families possess, accounting for about 70% of median household wealth. Over 2021, the value of US housing stock jumped by $7 trillion, hitting $43.4 trillion total.

Real estate transactions have long been considered ripe for disruption because buying or selling a house is time consuming, confusing, and laden with hidden expenses. Yet residential real estate has been slow to innovate—it’s the “largest, undisrupted market in the US,” according to Opendoor.

When it comes to buying and selling, real-estate tech—or “proptech”—is changing three things, says Zach Aarons, cofounder of venture capital firm MetaProp. “One, it can showcase listings,” says Aarons, calling back to Zillow’s initial success as a one-stop shop for seeing what’s on the market. Second, startups started digitizing time-consuming processes that have “fundamentally been pen-and-paper for centuries.”

“How do we deliver a title policy with more transparency, more accountability, quicker timing?” he asks. “How do we have e-closing, e-notarization? I think the pandemic accelerated a lot of that.”

The third matter, valuations, remains by far the thorniest. Automated valuation models (AVMs) are proprietary data systems that take in sales prices from the US’s 600 multiple listings services—the real estate agent’s bread-and-butter data—and combine them with information from mortgage lenders, public data sets, and map data like Yelp reviews of local bars, plus private data sold by real estate analysts. First-party data is increasingly accumulated, too: Opendoor created an app for in-person inspectors, pre-covid, with a 100-point checklist, while today, sellers perform self-service virtual assessments.

Opendoor’s tech chief, Ian Wong, says the foundation of their work is data cleansing—taking partial, duplicated, and contradictory data and parsing it to produce reliable insights. But “human-in-the-loop” systems remain vital, he says. The company has real people annotate visual data, adding labels in a manner he likens to the processing done on crowdsourced platforms similar to Mechanical Turk.

One goal of this data work is to eliminate the so-called “lemons problem.” So far, AVMs have been able to access only a portion of the information that a family selling its home knows, explains Amit Seru, a professor of finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business—failing to appreciate architectural style, unruly neighbors, how light hits the porch on late summer evenings, and myriad qualities contributing to a house’s human appeal. Consequently, these AVMs can lead iBuyers to disaster when some sellers offer up “lemons” (dud homes, say, with stinking carpets) and others offer “peaches” (a charming home in a neighborhood full of amenities). By bidding an average price for both homes, the iBuyer ends up paying too much for lemons, while families with peaches—who feel harshly undervalued—refuse to sell.

Wong says that both deep learning and humans can help minimize such issues by, say, analyzing photos for defects like ugly power lines cutting across the yard. AVM advances have expanded Opendoor’s “buy box,” the subset of homes it can purchase, since its launch in Phoenix in 2014. iBuyers typically start buying cookie-cutter houses, priced between $100,000 and $250,000, that are relatively new and on modest-sized lots, according to research out of Stanford, Northwestern, and Columbia. In February, Opendoor explained that it had grown its buy box by 50%. “Today we are doing higher-price-point homes. We’re going to gated communities, age-restricted communities, things that are harder to price,” says Wong. “And we’ve been able to expand all the way to Atlanta … to the most recent market we announced, which is the San Francisco Bay Area, which has very heterogeneous housing types.”

But how effective has this valuation technology actually been? Zillow has revealed that it lost $881 million on Zillow Offers. In a letter to shareholders, CEO Rich Barton explained that the venture was “too risky, too volatile to our earnings and operations”; it provided “too low of a return on equity opportunity, and too narrow in its ability to serve our customers.” The pivot forced the company to lay off 25% of its staff and left it facing two class action lawsuits from shareholders. Other iBuyers have a better record of profiting from sales yet are losing money overall, with Opendoor reporting a net loss of $662 million for 2021, its shares falling as measures of profitability were cut. The company, though, is bullish on growth, predicting a 460% increase in revenue in the first quarter of 2022 compared to one year ago. “In short, Zillow is out of the game, but Opendoor is getting bigger and stronger,” says DelPrete.

Database: America

Zillow’s pricing failures wiped out more than $35 billion in market value by February 2022. For buyers like him, Maxson says, “It’s insane! They’re falsifying the market.” Despite concert tours torpedoed by covid, Maxson says, he’s lucky to have kept earning a living, but he fears his neighbors will struggle: “A blackjack dealer and the husband does maintenance at the MGM [casino] … How do they try to navigate this if they want to buy a house?”

iBuyer purchases increased significantly in 2021

Making sense of iBuyers’ erratic transactions means understanding not just how their technology works, but where they come from, explains DelPrete. Tech-led disruption of real estate is not the result of a couple of buddies in a garage, he explains: “There are no pure tech plays that are revolutionizing real estate.” The fuel is billions of dollars that investment firms are pouring into housing, with Opendoor backed by $400 million from SoftBank, among other giants. The upheaval Maxson witnessed is one “downside of having a for-profit Wall Street–funded corporate middleman involved in the real estate transaction,” says DelPrete. “The company’s winning. Somebody has to lose.” But the impact is also felt by consumers, neighborhoods, and cities.

iBuyers’ primary benefit is supplying liquidity to a market where transactions are onerous. For a busy family, selling to an iBuyer can cut the need for presale repairs and viewings. For someone offered a new job in a faraway city, it can mean saying yes to relocating right away. Thousands of sellers have been willing to take an average $9,000 discount for this speed and simplicity, according to the NBER working paper. iBuyers’ arrival in new cities gives consumers extra options, offering fair bids and often lower agency fees than conventional agents, says DelPrete.

“The company’s winning. Somebody has to lose.”

Mike DelPrete

Drew Meyers, founder of Geek Estate, a private and paid community of more than 500 proptech executives and a Zillow alum, says it’s crucial to see iBuyers in the context of other proptech innovation, which also includes “power buyer” startups that allow homeowners to “buy before they sell.” VC investment and cheap debt are key here, too: “Most of the innovation is finance-driven, frankly,” says Meyers. “A lot of these companies are disguised as real estate companies, but they’re really fintech plays.”

One clear example, investment marketplace Roofstock, provides a platform that has helped investors put $5 billion into buying single-family homes to flip into rentals, often without a buyer ever entering the home. Roofstock compares prices, rental yields, and risk, giving a one- to five-star “neighborhood rating” based on factors like school districts and rates of employment. “We built a database of all roughly 90 million homes in the US, where we started with tax and deed information and then augmented it with ownership information, rents (if it’s a rental), evaluation information, all that,” says Gary Beasley, Roofstock’s CEO. “So we have this living, breathing database of every single-family house in America. And we overlay our neighborhood scores and transactional data, and really have a view on what every home is worth as an investment, right?”

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();

Today investors buy 27% of single-family homes in the US. Four in 10 are bought by small-scale investors owning fewer than 10 homes—who may buy in their home neighborhood or use tools like Roofstock. These buy-to-rent purchases are today a lightning rod for criticism, with investors outmuscling first-time buyers for scarce starter homes and reducing the number of affordable homes later sold. By “equity-mining” neighborhoods where families could once build wealth, investors instead capture the uplift themselves.

Dashboards like Roofstock’s are the mostly unseen war rooms in America’s housing chaos, helping faraway speculators make big returns while playing havoc withthe lives of people on the ground. In interviews with startups as well as real estate agents and analysts, it emerges that when a family finds its dream home, it has often already been crawled by AVMs that have analyzed its value as an asset, its potential yield as a rental, its forecast price growth, and countless other metrics.

Wall Street elite

Some of the world’s biggest real estate investors are guided by in-house systems that remain black boxes—and whose insights are fiercely guarded in Wall Street towers.

Private equity giants like Blackstone and Starwood Capital bought foreclosed homes in the aftermath of the subprime crash in 2008, bundling them into single-family rental empires, including Invitation Homes and Starwood Waypoint. These merged in 2017 to create the US’s largest single-family landlord, with a portfolio of 82,000 homes. Again, as in the subprime crisis, homes were transformed into tradeable asset classes worth billions. Cloud-based property management technologies underpinned these landlords, explains Steve Weikal, real estate tech lead at the MIT Real Estate Innovation Lab. These allowed firms to manage everything—from rent collection to home maintenance—in geographically dispersed homes, as easily as corporations had managed apartment buildings. Bigger tools followed, like Blackstone’s Real Estate Data Direct, which since 2021 has pooled data from hundreds of companies it owns while amassing the world’s largest portfolio of commercial real estate, now valued at $514 billion.

To support MIT Technology Review’s journalism, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Many Wall Street pioneers sold their rental businesses in the decade after the crash, making billions for investors and executives but leaving a trail of anger from tenants who endured poor maintenance and rent hikes. Yet coming into the pandemic, Wall Street had again assembled an unimaginable arsenal with which to strike deals—around $2.3 trillion. It was preparing, suggested the Wall Street Journal, “for what could be a once-in-a-generation opportunity to buy distressed real-estate assets at bargain prices.”

These firms are reinvesting in a big way. Blackstone bought Home Partners of America, with 17,000 homes, for $6 billion in June 2021. Toronto-based Tricon launched a $5 billion joint venture in July to buy up 18,000 homes across the Sun Belt. Indeed, many proptech innovations were developed by these Wall Street giants, with Blackstone alumni leading disruption from VC firm Fifth Wall and European pioneer IMMO. Roofstock founder Beasley was co-CEO of Starwood Waypoint Residential Trust, one of the US’s largest single-family rental companies, and sees his startup as disseminating the same tech tools. “The idea with Roofstock really was to take a lot of that knowledge of how we could package up and sell and manage single-family rentals, and offer that as a service both to institutional investors as well as individual investors,” says Beasley.

“That’s 7,000 families that didn’t have a chance to buy a home.”

Mike DelPrete

But links between Wall Street and proptech go further. A Bloomberg investigation found a “secret pipeline” of sales from iBuyers to big investors accounting for one in five homes they sold. The rate is double that, around 40%, in some Sun Belt metro areas, with many sold off-market. “That’s a big issue,” says DelPrete. “If that was 7,000 transactions, that’s 7,000 families that didn’t have a chance to buy a home just because a company decided not to list houses for sale.”

Fighting back

Last October, Los Angeles city council members Nithya Raman and Nury Martinez sounded the alarm that startups and Wall Street threatened to put an end to the American Dream. “It shouldn’t be impossible for Angelenos to remain in the neighborhood they grew up in or for hardworking families to purchase their first home,” says Martinez. “Angelenos just can’t compete with the money and power of iBuyers.”

In a motion, they instructed the city’s legal departments to seek ways to limit such speculative practices in order to rebalance the playing field. California had already restricted its SB9 law (which allows homeowners to develop another property on their lot) to those who commit to living on-site for three years, explained Meyers, to exclude corporate landlords. Maxson, who eventually found a home with the help of a regular, human agent, agrees with the move: “I think they need to be regulated. They’re taking a problem in the United States and making it worse.”

But some caution against clamping down on disruption. In a market ingrained with a history of racist practices—and where the appraisal industry remains 84% white—AVMs can mean fairer deals for minorities, explains Lauren Rhue, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland.

A landmark study in September confirmed anecdotal evidence of an “appraisal gap,” showing that homes in Black and Latino neighborhoods are consistently undervalued. Freddie Mac analyzed more than 12 million mortgage records between 2015 and 2020 and found that in Latino neighborhoods appraisers were twice as likely to value homes below the eventual sale price, with similar outcomes in Black neighborhoods.

Rhue is concerned that “what you could see is just a perpetuation of the issues that we’ve had historically in this country with housing.” Indeed, machine learning can entrench problems when fed data influenced by decades of discrimination. Home values—which are 55% lower in majority Black census tracts, on average, than in white areas—are a prime example.

A viral TikTok video by Nevada-based real estate agent Sean Gotcher made headlines in September by demonstrating how iBuyers might attempt to manipulate prices. “Let’s say that that company buys 30 homes within a two-mile radius, and let’s say the price is $300,000,” Gotcher explained. “Then on the 31st home, they buy it for $340.” Although overpaying, this new “comp” means they have a benchmark to sell the rest at $340,000.

Most analysts agreed that iBuyers are not big enough to pull this off. That would mean owning a big share of the local market, and restricting supply to drive sale prices up. But there are already signs big investors are restricting supply, further exacerbating housing crises and setting a template that any big iBuyer could follow. New York corporate landlords “warehoused” up to 50% of homes during the first covid-19 lockdown—keeping them empty to restrict free-falling rents. On a smaller scale, Opendoor continued buying homes in the winter of 2020, but curiously stopped listing them for sale.

For ordinary people, so long as Wall Street cash is flowing into housing, Zillow’s failure is not the end of tech-led disruption but a fumbled beginning. “iBuying, power buying, co-investments, down payment assistance, cash offers,” says Meyers. “They’re all going to end up doing it all.” Each company is now trying to capture and automate more of the value of the transaction chain that has traditionally been split between mortgage brokers, flippers, title agents, real estate agents, and more. The core mechanics—tech to value homes and manage deals, married with free-flowing finance—give entrepreneurs room to reinvent the offer. Some innovations may be boons for prospective home buyers. But just as surely, others will empower the most cut-throat investors in the world.

Matthew Ponsford is a freelance reporter based in London.

[ad_2]

Source link