[ad_1]

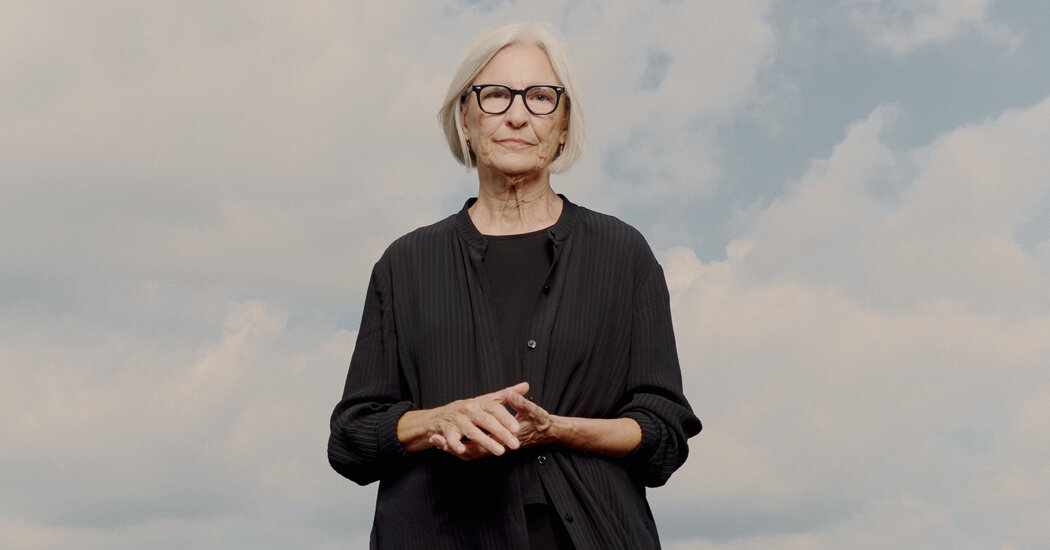

“Being a boss is not my forte,” Eileen Fisher said, shifting in a chair from the sleek boardroom at the company headquarters where she started 40 years ago.

That may seem surprising, given Ms. Fisher, 72, who has established herself as a leader in a brutal industry characterized by constant change.

After all, she is a designer who has built a fashion empire. In an industry where, by some standards, a truckload of clothing is burned or buried in landfills every second, she was an early pioneer of environmental protection as a primary cost of production. In the year She is the founder of a company that decided in 2006 that instead of going public or acquiring a business, she would transfer ownership to her employees.

But front and center has never been Ms. Fisher’s style. For most of its history, Eileen Fisher (the brand) did not have a CEO, opting for “affiliate teams” of various shapes and sizes. It was only in the last 18 months that the company even got a CEO in the form of Eileen Fisher (the woman). After Brand said she had “lost her way,” she went out to steady the ship.

Now, the queen of late fashion is ready to relinquish that role (albeit slowly), as part of what she describes as a “responsible transition” away from the spotlight. This latest step back will allow her to focus on refining her design philosophy, she says, adding that the brand can eventually exist without her.

“Being a CEO has never really been a part of who I am – it’s never been something I’ve been comfortable with,” Ms Fisher said. “I like to think that I lead myself in the thought.” Her signature bob sparkled like a pearl helmet, hovering over her dark glasses as she spoke. She’s draped in one of the gorgeous, wide-brimmed sweaters she’s made a name for herself, and in the process has created what The New Yorker calls a “delightful field cult.”

“I have a vision for how this company is going to move forward, but I know I’m not the one to execute it,” she added. “Not by myself, anyway.”

Just do a little

After more than a year of searching, Ms Fisher said she was delighted to have found a replacement. In early September, Eileen Fisher’s new CEO, Lisa Williams, will become Patagonia’s current chief product officer.

On paper, at least, Ms. Williams seems well suited. Another typical retailer is Patagonia, which donates 1 percent of its sales to environmental groups, as well as visionary founder and like-minded Eileen Fisher on how products can be made, worn and — ideally — recycled.

Ten years ahead of many of her competitors, Ms. Fisher In 2009, she launched her upcycling line, which sells second-hand clothes and an organization called “Trash Now More” that takes discarded clothes and turns them into textiles. Patagonia was also an early adopter of organic materials, has a long history of political activism and once ran an ad telling people not to buy its products.

“The fashion industry is in a terrible state of chaos, with too much stuff and rampant overproduction and overconsumption,” Ms. Fisher said. “How do we begin to make sense? How do we grow our brand without increasing our carbon footprint? I find that Lisa and I are very similar when it comes to scratching the surface of these complex conversations.”

Ms. Fisher pointed out that the two women were in complete agreement not to be driven solely by financial results. (Likewise, Eileen Fisher has been profitable for about two years since its inception, the company said, with sales of $241 million last year.) And few are as knowledgeable or as connected when it comes to the complex business as Ms. Williams. The fashion supply chain, a global and murky ecosystem where many brands have little or no knowledge of who makes their clothes.

“One of the most important ways we can both be sustainable is to reduce,” Ms. Fisher said. “Do less: buy less, eat less, produce less. It’s a tough line to walk when you’re trying to run a business, and you’ll measure your success by how much you sell. But I needed someone completely on board with this.

Ms. Williams, a 20-year Patagonia veteran, said in a phone interview this week that she feels “familiarized and admired” with the Eileen Fisher brand and her business approach.

“The unusual leadership structure there doesn’t bother me – I’m really in my comfort zone when things seem unusual,” said Ms Williams, who has never held a CEO role before. “I think the idea of collaboration and cooperation can work in a company.”

“The last few years have been very difficult for anyone in retail, let alone those trying to change fashion trends,” Ms. Williams continued. “And I have a lot of credit for what Eileen and her team did through that chaos to bring the brand back to its original values.”

Part of getting things back to normal included ditching some of the bolder colors and prints that had begun to creep into the collections, instead re-emphasizing the labels Ms. Fisher is known for. The latest clothes on her website come in a muted color palette with shades like ecru, cinnabar and oat. Things like kimono jackets and sleeveless tunics and cropped palazzo pants in soft cotton or gauze and Irish linen are uncomplicated and designed to flatter. The important thing now is to find a way to use those forms for the next generation.

‘I wasn’t really a typical fashion designer.’

The success of high-end luxury brands such as the “Beach Grandmother” Tik Tok trend and Jil Sander and RD suggest that minimalist capsules – collections of clothes made from flexible materials, therefore increasing the number of clothes that can be created – are a renewed fashion moment. There seems to be a shared desire for simplicity — something Ms. Fisher has consistently offered since the mid-1980s, and her first designs for kimonos she saw on a trip to Kyoto.

When she started in 1984, Ms. Fisher was a recent graduate of the University of Illinois. The second of seven children raised in Des Plaines, a suburb of Chicago, she first came to New York to become an interior designer. (She had $350 in her bank account and didn’t know how to sew.) But she wanted to liberate women by giving them formula.

The simplest thing, her thinking goes, is that the more things go, the longer you wear them, the longer they stay in your wardrobe. It was an approach she felt would resonate with young women today, remembering that they can choose what they believe in with their wallets, even if it makes their clothes more expensive.

“It’s hard to convince people to buy less when they’re making a long-term commitment, but I want them to see that they have a choice when they buy into our capsule system,” said Ms. Fisher, who says she’s found crossover among seniors. And on pieces that younger shoppers love (box tops are a runaway, she said). And it’s a trend that’s influencing not only young consumers, but young designers as well.

“Eileen was one of the few industry leaders who made me feel like my company’s success was possible,” said menswear designer Emily Bode, who Ms. Fisher said was “incredibly encouraging.” As a basis for her own brand.

“When I was going through growing pains with Bode, I visited with Eileen and her team,” Ms. Bode said. “Her dedication to retail, slow growth, being privately owned, and creating an unconventional but successful business model that embraces recycling and sustainability has shaped my business strategy and success.”

Looking back at past interviews, it’s clear that Ms. Fisher has been struggling with how to detach herself from her brand for some time. She spoke repeatedly over the years about how she felt if she no longer needed to be there; She talked about the idea that the company developed beyond her. And yet, here she is, still some way from release.

“These verses were true in their time,” she said. “But I think, over time, I realized that simple clothing and design, and the idea of how we’re going to spend money here, didn’t really take off in the company the way I thought it would. I had to go back to the center and reorganize things so that people knew exactly how things were supposed to work. It is an important part of my legacy and what I leave behind.

With Ms. Williams’ imminent arrival, Ms. Fisher expects a little more free time. She says she doesn’t want to travel, preferring instead to spend more time doing Kundalini yoga and meditating, playing mahjong with friends and learning how to cook good Japanese food. She also has two grown children, Sasha and Zach; She wants to spend more time with her.

But Ms. Fisher is clearly not done. For one thing, outside of the office, she wants to focus on education through her charity, the Eileen Fisher Foundation. She also fantasized about starting a design school.

And she wants to make sure her employees — all 774 part-owners of her brand — are ready for what’s to come. Being a private company and giving its employees a stake in the business have both been a big part of its success.

“I hope that what we’re building here in Irvington is a relatable concept that 30 years from now, the example of what we’re building is something that other people can try and build,” Ms. Fisher said, referring to the city. On the Hudson River where you live and work.

“I don’t do trends. I don’t do runways. I was not a normal CEO,” she said with a small smile. But then again, I guess I’ve never been a typical fashion designer either.

[ad_2]

Source link