[ad_1]

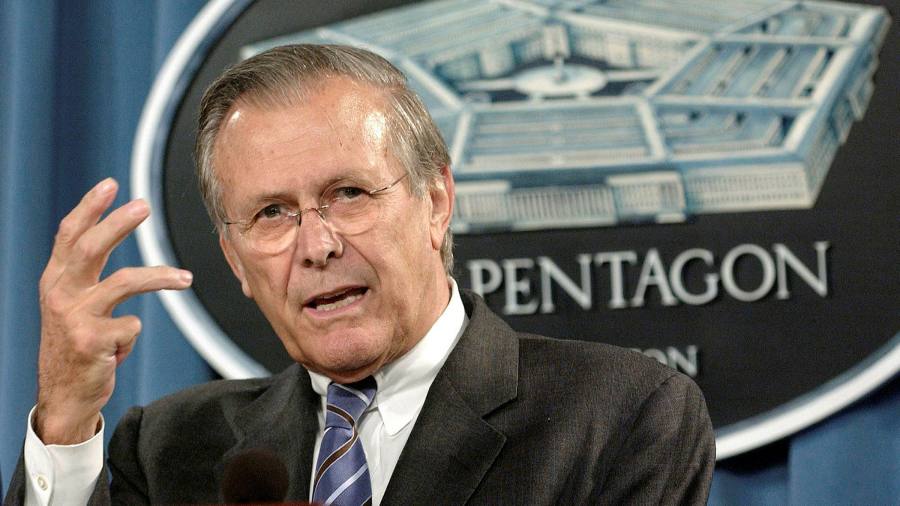

Donald Henry Rumsfeld, who has died at the age of 88, he had the unique distinction of being the youngest and oldest man to serve as U.S. Secretary of Defense. His seasons in the workplace, separated by a quarter of a century, were shaped first by the Cold War and then by what he called “the world war on terrorism.” He was branded as a comfortable military strategist for challenging Washington orthodoxy and projecting American power abroad, a worldview he applied with self-confidence that bordered on arrogance.

Critics argued that his unwillingness to loosen dissent colored his ultimate legacy: helping to convince the president George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003 after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Rumsfeld, who had supported Saddam Hussein’s Iraq attack even before rejoining the government as secretary Bush’s defense in 2001, became the main animator of the invasion within the administration. He overturned generals in deployment schedules and ignored diplomats urging him to carry out detailed post-war planning. He then took much of the blame when a quick military victory against Saddam turned into a scathing counterinsurgency for which the United States was ill-prepared.

Rumsfeld, circa 1975 © Getty Images

Rumsfeld was born in the Chicago area on July 9, 1932, the son of George and Jeanette Rumsfeld. He grew up in the Winnetka neighborhood of Chicago, where he became an Eagle Scout and attended New Trier High School. The Rumsfeld family also lived briefly in Coronado, California, during World War II, when George served in the United States Navy with an aircraft carrier.

After graduating from Princeton University, where he was part of the wrestling team, Rumsfeld he became a naval pilot in 1954. The same year he married Joyce Pierson, with whom he had two daughters and a son.

After demobilization in 1957, he went to work in Washington as a congressional attendee, before spending two years as an investment banker in Chicago. In 1962 he was elected to the United States House of Representatives as an Illinois Republican and served three terms. He resigned in 1969 to join the new administration of Richard Nixon as director of the Office of Economic Opportunities, a now-defunct agency responsible for administering anti-poverty programs. One of his first recruits was Dick Cheney, who later as vice president of the United States influenced his return to the Pentagon in 2001.

President Ronald Reagan and Rumsfeld, then sent to the Middle East, held a press conference at the White House in 1983 © AP

Rumsfeld meets Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 1983 © Getty Images

Rumsfeld prospered in the country’s capital. In 1971 he was appointed director of the economic stabilization program and two years later was sent to Brussels as the US ambassador to NATO. But Nixon’s resignation in 1974 brought him home, first to lead President Gerald Ford’s transition team and then as White House chief of staff, with Cheney as deputy and later successor.

In 1975, at the age of 43, Rumsfeld became the youngest secretary of defense in history. The circumstances of his appointment were unfavorable. His predecessor, James Schlesinger, was fired by Ford after repeated disputes with Henry Kissinger, then Secretary of State.

Once installed in the Pentagon, Rumsfeld proved to be a shrewd bureaucrat. He seemed to have inherited a poisoned chalice. The military was not only in the midst of a transition to a fully voluntary force, but also demoralized by its defeat in the Vietnam War. In addition, the political tide had turned against rising defense spending.

He faced these challenges head on, pushing for new armed service reforms, the development of the cruise missile and the B1 bomber, a prototype of which he flew as a pilot, more ships for the navy and, of course, a larger budget. He justified his ambitious plans on the grounds that the threat of the former Soviet Union demanded nothing less and, in its first year, secured substantial additional federal funding.

Rumsfeld meets then-Afghan leader Hamid Karzai at Bagram airfield in 2001 © Reuters

Rumsfeld shakes hands with members of the US military in an undisclosed location near the Afghan border in 2001 © Reuters

But he also fell with the military. He overturned them with a conservative design for the M-1 tank, designed as NATO’s main combat vehicle, when he insisted it would house American and European-sized weapons. And he publicly disciplined General George Brown, then chairman of the joint U.S. chiefs of staff, after an undiplomatic outburst that, among other things, described the British army as “a pathetic vision.”

The democratic victory in the 1976 elections led Rumsfeld to start a career in the private sector. He served as CEO and later chairman of GD Searle, the Chicago-based pharmaceutical company, before leading General Instrument Corp., a pioneer of high-definition television. From 1997 to 2001 he was president of Gilead Sciences, an American drug manufacturer best known for its HIV drugs.

US Marines applaud Rumsfeld when he is presented at a town hall meeting at Camp Pendleton, California, in 2002 © AP

Rumsfeld in the hold of a C-130 military plane while flying over Iraq in 2004 © AP

Although he did not return to the cabinet during the Republican administrations of Ronald Reagan or his rival George HW Bush, he remained an influential spokesman on security issues and briefly weighed in for the presidency after Reagan’s second term ended. 1988. Appointed in 1998 by the Republican leadership in Congress to head a commission on ballistic missiles concluded that the threat posed by “rogue” states, such as North Korea, was serious. His report grounded the case, adopted by George W Bush in 2001, for a national missile defense system. He also publicly argued that Saddam should be removed by force if necessary.

His return to the Pentagon in 2001 was not without problems at first. He immediately ordered a fundamental and comprehensive overhaul of the structure of the U.S. armed forces, but the consultative process that ensued alarmed the Conservative military.

Rumsfeld was reluctant to push for a larger defense budget. In a sense, he was ambushed, as the new Bush administration intended to pass deep tax cuts and did not want to implement large increases in departmental spending. But his reluctance made him unpopular in some right-wing circles. In the summer of his freshman year, several experts called for his replacement. That changed with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. After a airliner was sent to the Pentagon, he ran out of his office to try to rescue those trapped, which made him admire the staff. .

Rumsfeld speaks with Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, then commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, in 2004 © EPA

Rumsfeld and then-Chinese Defense Minister Cao Gangchuan attend a welcome ceremony at the Chinese Ministry of Defense in Beijing in 2005 © Reuters

Rumsfeld will be remembered not only for his bureaucratic skill, but also for his aphorisms. His admission in 2002 that there were “known acquaintances” and “known strangers” about the Iraqi government’s program for weapons of mass destruction, although initially mocked, became part of the political lexicon for leaders who they dealt with complex problems.

Rumsfeld resigned in 2006 after Republicans were mistreated in the midterm elections amid growing public discontent over the Iraq war. He retired for much of public life, but published two books: a 2011 memoir entitled Known and unknown and a 2013 advisory volume called Rumsfeld’s rules: leadership lessons in business, politics, war and life. He also participated Documentary by Errrol Morris about his life.

In his later years, he launched a mobile gaming app called Churchill Solitaire, based on a version of the card game played by the late British Prime Minister. And six months before he died, he co-authored an opinion piece in the Washington Post alongside nine former U.S. defense secretaries, warning that the military should not play a role in Donald Trump’s efforts to prevent Joe Biden became president.

[ad_2]

Source link