[ad_1]

In the past few weeks, there have been many signs that China’s largest technology industry is out of the doghouse.

Since the end of 2020, companies in the sector have faced new and often onerous regulations, from fintech and data protection, to online competition and youth protection. The online education industry has virtually disappeared as longtime investors such as e-commerce giant Alibaba and video games behemoth Tencent saw their share prices plummet.

But of late, olive branches are appearing. In mid-January, Hangzhou Party Secretary Liu Ji signed a strategic agreement with Alibaba, which has its headquarters in the city. In a related speech, Liu said that the future regulation will be implemented “with forgiveness and caution”. In the year A failed initial public offering at the end of 2020 took a tour of Alibaba’s fintech spin-off Ant Group, which created talk of “tech” in China. More recently, Ant received regulatory approval to inject funds into its consumer finance division; As part of the deal, Hangzhou Jintu Digital Technology Group, controlled by the Hangzhou government, will take a 10 percent stake in the unit. In another announcement, the company confirmed changes to its voting structure that will mark the end of Jack Ma’s control, with his voting weight reduced from more than 50 percent to 6 percent.

In another dramatic example of relaxation, ride giant Didi, which was fined 8 billion yuan last year for a cyber security breach, has begun adding new customers to its service for the first time in 18 months. Guo Shuqing, director of China’s banking regulator, said this month that efforts to fix the financial operations of 14 large tech platforms are “basically complete.”

So after all this, about $1.5 trillion has been wiped from the market value of China’s technology platform companies, we are left with two simple questions: What has changed in the past few years, and what now?

First of all, we should show some caution about framing the regulatory wave from 2020 as a “technological failure”. When it started, it wasn’t about all the tech companies, just the big consumer-focused platforms like Alibaba and Didi. Businesses in advanced robotics, biotech or enterprise software, for example, were least affected.

Moreover, the word “bang” itself indicates that this was a coordinated but temporary event, which was planned to reduce the economy of the stage to its size. Indeed, the level of coordination in Beijing may have been exaggerated: the regulatory campaign involved many officials, all with their own agendas and policy objectives. For example, moves to regulate fintech have a different logic than those intended to regulate competition between platforms. Nor is this a short-term event, after which the previous situation will resume. It is more correct to see the measures of the last few years as a “correction”, where the authorities sought to introduce new and permanent regulatory tools and requirements on economic activities that affect the lives of more than a billion consumers.

… Beijing has made it clear that technology platforms must act as good citizens, bearing primary responsibility for the impact of their content and business models, and contributing to the Party’s overall social and economic policy goals.

Finally, throughout the “campaign” (and with the exception of the for-profit education technology sector), officials have underlined their importance to the platform economy. Perhaps on the contrary, the signal’s importance seems to be that the undeniable excesses of restraint built up over the centuries benefit the sector and the wider Chinese economy.

It has been tempting to say that this correction was motivated by political and sometimes gossipy reasons. On this reading, the main driver behind the movement of the last few years is Xi Jinping’s desire to cut Jack to size. There may be a grain of truth in this, but it doesn’t explain why so many other unrelated companies are caught. Bureaucratic factors also played a role: the newly established Regional Market Regulation (SAMR) used the introduction of competition regulation to raise its profile and increase its access to finance and resources. Among other measures, it established a new anti-monopoly office.

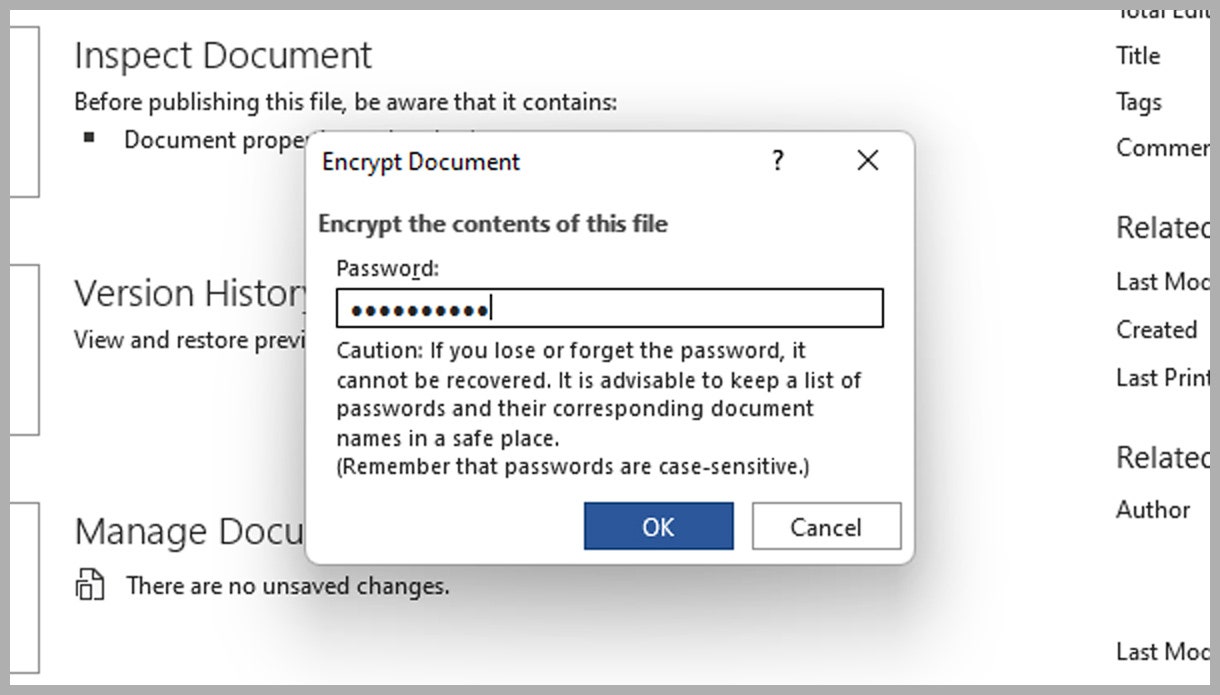

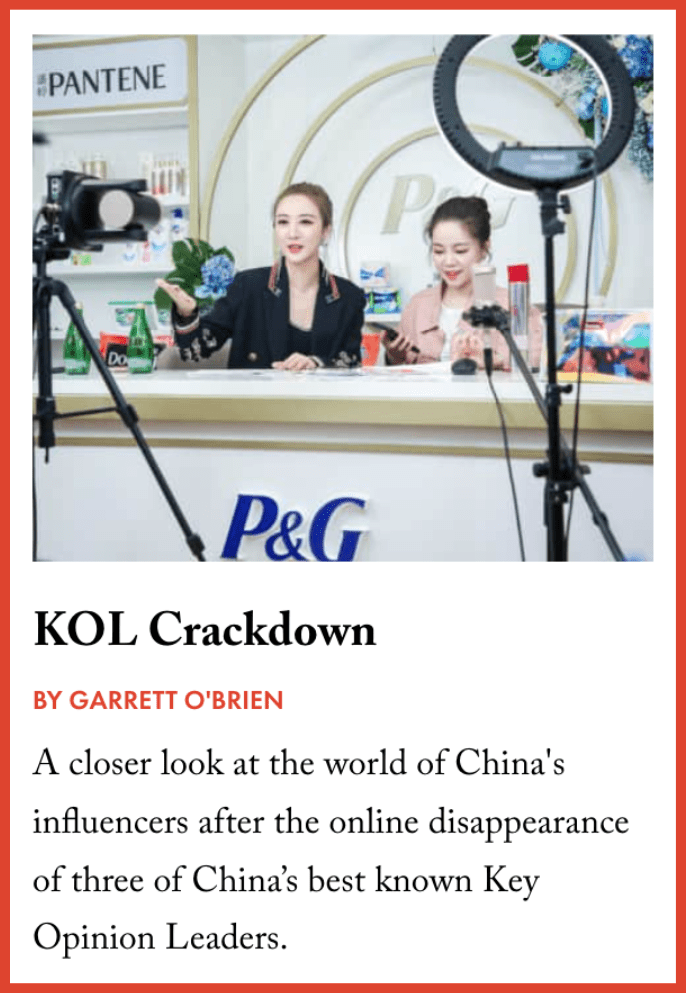

However, it is clear that there are several practical reasons behind the adjustment. In some respects, these aren’t new: controls on algorithms used to recommend content and AI-generated content are just the latest in a long line of laws put in place in China for the production and distribution of information online. In other cases, the goal is to extend the existing rules to the platform area, adjusting them in areas that are important for the specific properties of the sector. The ban on the “9-9-6” work culture in the technology sector and better protection for drivers is based on existing labor laws, for example; Many of the “new” rules for fintech have already been applied to traditional banks. Applying competition laws to tech companies only when existing competition laws dictate how they should be applied to platforms. No new law is required to punish even tax-evading live streamers, such as popular online celebrity Via, which was fined 1.34 billion yuan in December 2021. In short, part of this correction has “recruited” big tech. Another Chinese industry, it avoids its hostile environment and its apparent vulnerability.

More importantly, Beijing has made it clear that tech platforms must act as good citizens, bearing primary responsibility for the impact of their content and business models, and contributing to the party’s overall social and economic policy goals.

What does this mean for the future of the sector? On the one hand, the amendment targets many of the obvious excesses associated with the tech industry, from companies playing fast and loose with user data to harsh and anti-competitive conditions platforms place on third-party vendors. Whether or not the goals of the adjustment will be achieved in the long run will depend on future performance. Either way, the restrictions on business models and rising compliance costs could permanently squeeze the profitability of platform companies. That’s not necessarily a bad thing: The winner took oxygen from everyone else, including the sector’s dynamic startups. If the measures behind the adjustment lead to a more equal distribution of income for all participants in the sector, it could be an example of achieving “shared prosperity”, a key policy of Xi Jinping.

… A sustainable Beijing approach must find a middle ground between innovation and profit on the one hand and political ambitions on the other.

However, many questions remain. Some of the new regulations, particularly in data protection, are still unclear and require more detail from regulators. For example, it is not clear how the authorities will regulate the mandatory registration of content recommendation algorithms. In other cases, the implementation and enforcement of regulations seems to follow politics. Here, the distinction between regulators is important: when SAMR fined Alibaba 18 billion yuan for competition law violations, it published a detailed legal argument to justify its decision. In contrast, the 8 billion yuan fine imposed on DD by China’s Cyberspace Administration appears to be based on rolling back the law. CAC’s decision letter dated It refers to offenses committed in 2015, three years before the relevant legislation came into force and 6 years before publication.

As China faces economic headwinds, it is critical to re-register the platform sector to serve economic growth. While the return to non-prohibition is clear, the Wild West era of past decades is out of the question, the cost of intervention is high, and a sustainable approach from Beijing must be creative and find a middle ground. Profit on the one hand, and political objectives on the other.

Rogier Cremers is Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese Studies at Leiden University. He leads the project on Chinese and international cyber security for the Leiden Asia Center. He is also the co-founder of Digi China in collaboration with Stanford University and New America.

[ad_2]

Source link