[ad_1]

AAfter four years Spruce up Tiffany & Co., the upmarket American jeweler, opened the doors of its flagship store on New York’s Fifth Avenue to the public on April 28. At first glance, the Great Enlightenment seems premature. Hours earlier, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that consumer spending in the U.S. rose sharply in March, amid stubbornly high inflation and a slowing labor market.

Yet the well-heeled New Yorkers who lined up on opening day to step inside what Tiffany modestly rebranded as “The Landmark” hinted at a more complicated story. Tough economic times, like never before, have pushed consumers to shop at budget-friendly stores and products, boosting business performance. But wealthy households remain flush with cash, leaving businesses that cater to the wealthy buoyant. That raises uncomfortable questions for companies that offer their customers either economy or luxury, but something in between.

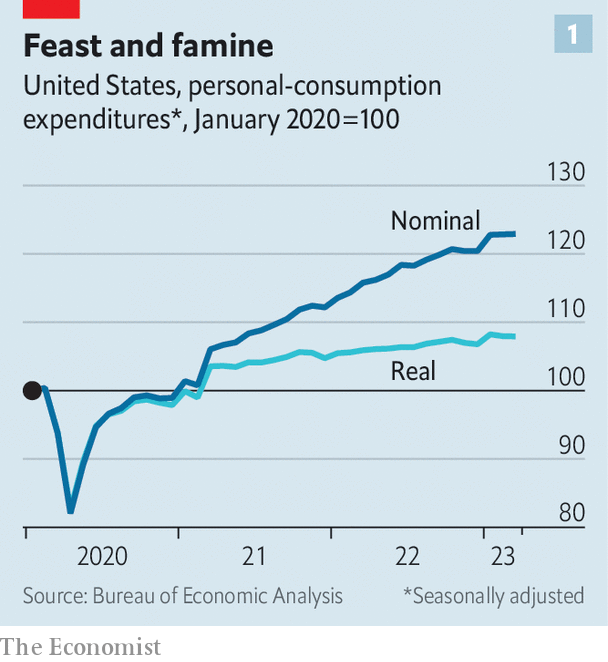

It’s been a roller coaster three years for American consumers — and the businesses that serve them. In the year In early 2020, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic led to higher spending, which led to a slowdown in demand (see Chart 1). Even low-income households got in on the fun, spurred by sweet stimulus checks and wage increases for low-skilled workers as businesses scrambled to hire waiters, store clerks, and the like.

Then, around 12 months ago, rising inflation caused consumers to start tightening their belts despite wide disparities in the income distribution. Fueled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, skyrocketing food and fuel prices and skyrocketing rents have pushed families below the income level, especially given the high share of spending on such essentials. In the year By 2022, inflation for households in the bottom income quintile was one-fifth higher than in the top quintile, Goldman Sachs said, offsetting faster wage growth among low-income earners (see Table 2).

As annual U.S. consumer-price inflation begins to moderate, falling to 5.0 percent in March from an average of 6.5 percent last year, higher prices are weighing heavily on the less wealthy, Gregory Dako said. EY, consultant. Additional household savings accumulated during the pandemic have declined from a peak of around $2.5trn to $1.5trn in mid-2021, according to Joseph Briggs of Goldman Sachs, most of which is now held by high-income households. Wallets at the top of the income distribution have also been fattened by rising property prices in recent years, said Paul Lejuz of Citigroup, another bank. Although markets have fallen off their highs, S&P Compared to January 2020, the 500 largest companies increased by 26%. House prices increased by 38%.

This imbalance in consumers’ financial health has two effects. At first, wallet-friendly businesses on the price spectrum signed up new customers. While the poorest households cut back on all essential expenses, the middle-income – those with larger shopping carts – are turning to cheaper stores and brands, said Morgan Stanley’s Sarah Wolff, an additional banker.

Analysts estimate that sales at the Burlington discount department store rose 13.2 percent in the first quarter of this year, compared to a 4.2 percent decline for Macy’s, a middle-class stalwart. Growth at Walmart, the thrift-backed big-box retailer, is expected to register a respectable 4.9% for the US last quarter, while Albertsons and Kroger, two mid-sized supermarkets, are expected to grow at a modest 2.5% and 1.3%, respectively. A similar pattern is emerging at retailers: In-house brands like Walmart, which raise prices to protect sales margins, are taking away from brand-name suppliers like Procter & Gamble and Unilever.

Consumers are bargain-hunting beyond supermarkets and department stores. On April 25th, McDonald’s, the purveyor of cheap calories, announced that it had hit a 12.6% sales increase for the first quarter compared to last year. On April 20 IKEAThe Swedish maker of affordable furniture and home furnishings said it was investing $2.2 billion to expand its presence in the U.S.—days before Bed Bath & Beyond, its midsize rival, declared bankruptcy.

The second disparity in consumer health shows that while affluent consumers move up in the finer things in life, businesses at the wallet-emptier end of the price spectrum continue to thrive. The U.S. luxury goods market grew 8.7 percent last year, outstripping inflation, according to market research firm Euromonitor (see Chart 3). On April 12 LVMHThe world’s largest luxury company and owner of Tiffany & Co. said first-quarter sales growth was 8 percent, year-over-year, in the U.S. — down from 15 percent in 2022, but still a bubble. Hermès, the purveyor of eye-poppingly expensive handbags, did not see a slowdown in sales in the U.S. in the first quarter. The design extends well beyond designer clothing. Luxury-car sales hit a record 19.6 percent of the total market in January, ending a two-year tear, according to data from another market researcher, Kelly Blue Book.

Bain adviser Claudia D’Arpizio helped the luxury business’s resilience by shifting focus after the financial crisis shifted from wealthy to positive cargo. The penthouse floor of “The Landmark” is entirely dedicated to such ultra-high-end consumers. While aspirational shoppers may splash out on a pair of Gucci sneakers in good times, those at the top end of the income distribution are loyal customers even when the economy seems shaky. That luxury has made it a less cyclical business than it used to be.

The center does not hold.

As consumer spending shifts to the two extremes of the price spectrum, some companies are already adjusting themselves. One strategy is to develop the most expensive regions. On April 3, L’Oréal, whose brands range from modestly priced Garnier to luxury luxury Lancome, said the beauty company would spend $2.5 billion buying $40 hand soap maker Aesop.

Other businesses are reducing exposure to the shaky middle ground. On April 14, Walmart announced it was selling midsize menswear brand Bonobos for $75 million, less than the $310 million it paid to acquire it in 2017.

A third strategy is to invest in supplies for the budget conscious. Video streams from Netflix to Disney have opened up ad-supported tiers, driven by increased subscription prices for consumers.

Investors would do well to take note. Conventional market wisdom dictates that businesses avoid doing business in “sensible” spending categories (cars, clothing, and other non-essentials) during tough economic times. The new logic of consumption suggests that the all-important tariff pedalers can do well as the economy falters. But so do the most savvy salespeople. ■

[ad_2]

Source link