[ad_1]

Childcare provider Demaris Elix knows firsthand how difficult it can be to find daycare in Central Oregon.

Elix After moving to the United States from Guatemala in 2013, she struggled to find care for her son, who has cerebral palsy. She said good programs were too far from her home in Bend, had long waiting lists or were too expensive. Unable to find a place, Elix stayed home with her son until he started kindergarten.

When her next child was born, Elix stopped working to live with him.

“We didn’t have a good experience for the first time around,” Elix said in a Spanish interview.

Now Elix is one of several new childcare providers opening in Central Oregon with the help of a program created by Central Oregon Community College’s Small Business Development Center and the nonprofit NeighborImpact. The idea serves several goals: helping working families open local small businesses by equipping adults to run successful child care businesses and providing more child care spaces in communities that need them.

The Early Childhood Education Business Accelerator helped 32 aspiring child care providers build business plans and learn how to obtain state licensing after accepting its first cohort in October. 16 participants received start-up grants of $5,000, and another five grants are under review. Central Oregon Community College says the accelerator has helped open 100 new daycare spaces so far, and organizers hope that number will reach 250, the goal they set when they started the project by the end of the year.

Elix opened her childcare business this summer using start-up funds provided by the program. She calls it a dummy house.

“The resources are there, the support is there,” Elix said. “You don’t just take classes and pay money, that’s it. They are always available to help you.

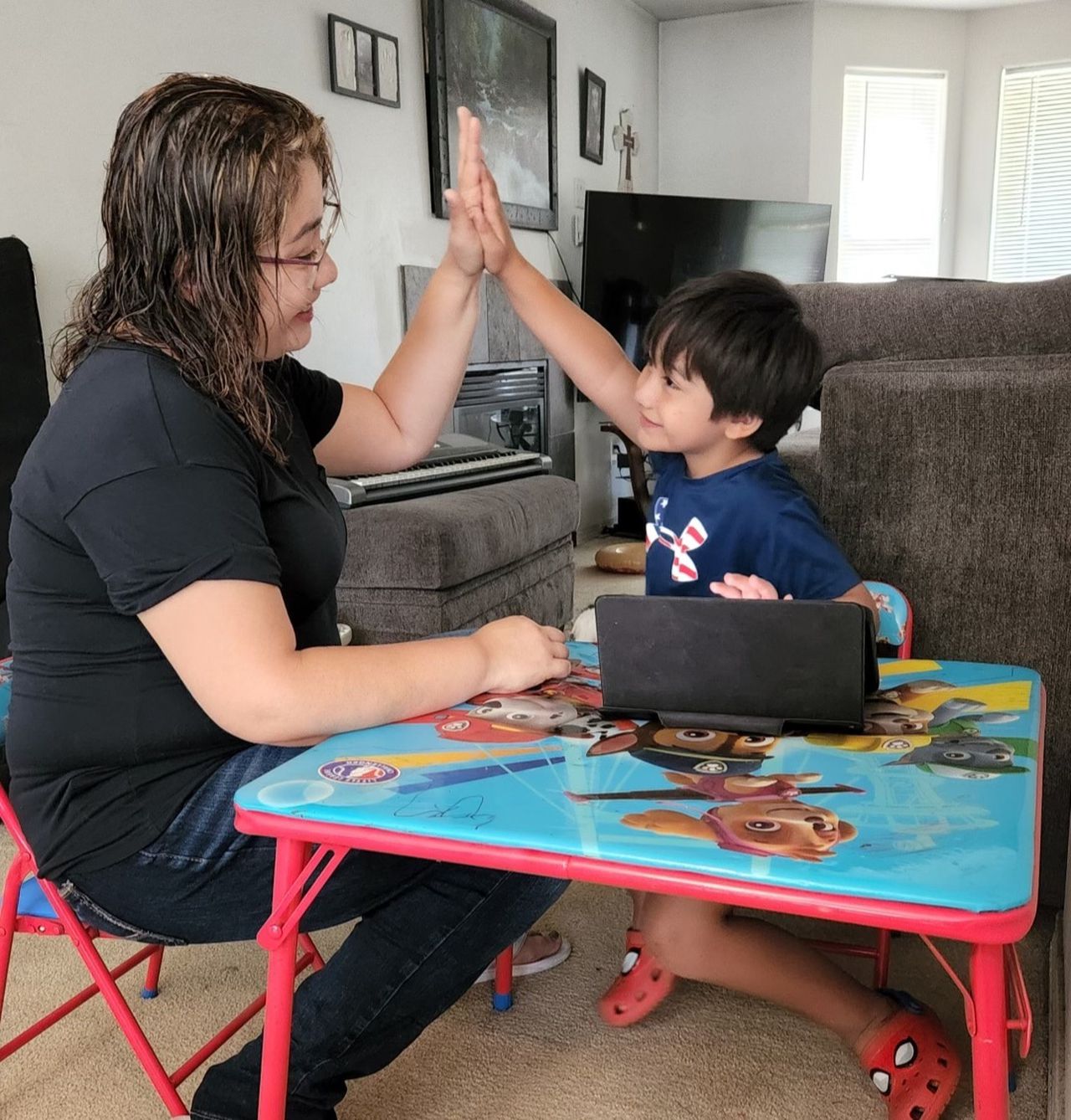

Demaris Elix raises her youngest son at her home in Bend. Elix is one of nine new childcare providers to complete the new Accelerator program in Spanish. Courtesy Damaris Elix

He refuses to take care of children at home

All of Oregon’s 36 counties are considered “child care deserts” for infants and toddlers, meaning there is only one child care spot for every three children that age, according to the latest 2020 report by Oregon State University. Approximately 70% of counties have similar shortages for preschool-aged children.

In Deschutes County, where Central Oregon Community College operates, only 22% of children ages 0-5 have access to child care, according to the report.

Small-scale, in-home child care providers are an important part of that landscape, says study co-author Megan Pratt, but they’re in significant decline. Between 1999 and 2020, Oregon lost 32,000 in small family child care homes, outstripping growth in larger facilities and reducing overall child care places over the past two decades, according to the report.

In-home providers are more likely to meet the needs of low-income families, offer weekend and evening care and offer more traditional offerings than larger child care centers, Pratt said. More than a third of small, home-based providers are people of color and 35% speak a first language other than English.

“They serve a very important purpose, and their numbers are dwindling,” Pratt said.

Pratt said the pandemic has changed the world of child care, and many facilities temporarily closed due to Covid-19 don’t know if they will reopen. The state of Oregon will conduct a new child care census this fall, and Pratt expects a slight decline in small and home-based programs and those that rely on private tuition instead of public dollars. Family and home-based programs were less likely to report receiving public funds during the outbreak, according to research from the Partnership for Preschool Improvement.

On the plus side, Pratt said the pandemic has brought “focus and urgency” to strengthening the childcare industry.

States have allocated more than $2 billion in federal pandemic relief funds to bolster the child care workforce, the White House reported last month. Deschutes County was singled out in the federal report for its efforts to train new providers and expand child care facilities.

More than 30 Central Oregon residents have completed the Early Childhood Education Business Accelerator since it began last fall. The accelerator helps future child care providers start their own businesses, and offers $5,000 in grants to help them do so. Photo courtesy of teacher Lisa Tynan.

Governments entered

The city of Bend approached Central Oregon Community College last year with a proposal to support home-based child care businesses, said Ken Bitskart, director of the Small Business Development Center. The college partnered with nonprofit NeighborImpact to launch the accelerator using $125,000 in grants from the City of Bend and Deschutes County, Sister Cities and the Small Business Development Network.

Organizers recruit students through community college, NeighborImpact and social media. The program is free, but students can expect to pay state fees to license their business. Denise Hudson’s NeighborImpact course completions are eligible for four college credits and may also apply for an internship scholarship to continue undergraduate education at Central Oregon Community College or Oregon State University.

The state has no educational requirements for registered family care providers who can care for up to 10 children in their homes, Hudson said, but older family care providers must meet a more stringent education or experience level.

A group of 15 new or aspiring vendors will spend three months attending intensive classes at Central Oregon Community College and working with a mentor to craft their business plans. The classes cover how to set up a business bank account, register with the state, file taxes, and develop an effective business model.

Participants who complete the program may be eligible for $5,000 in start-up funds to open their child care facilities and receive ongoing support from their staff after their businesses get off the ground.

Anna Spengler, who took the Acceleration Course last fall, said instructors help participants identify ways their businesses can offer something unique and allocate their budgets to create a realistic learning curve.

“I’m the type of person who puts a lot of receipts in a shoebox,” Spenger said. “I thought about how I was going to make the place and decorate it and kind of set the rhythm of the day. I didn’t think too much about the financial aspect.”

Karen Prow, with NeighborImpact, said the program helps providers plan for sustainable business operations, which in turn helps prevent children from moving from one daycare to another.

According to a 2021 report by Portland State and Oregon State Universities, child care wages are “significantly lower” than wages in occupations requiring similar education and experience. Lisa Tynan, an instructor at Accelerator, found that when she sat down with vendors to budget, they often paid themselves at or below minimum wage. One participant was paying herself just $4 an hour, Tinan said.

At the bare minimum, Tynan said the instructors try to help participants pay themselves above minimum wage based on their experience in the field and the quality of the program. Participants generally need about $20 to $30 an hour to make ends meet, she said.

The price providers charge parents depends on the costs of their specific programs, Tynan said. Investing portal Wonderschool Bend shows home providers with monthly rates starting at $200 to $400 and peaking at $1,500 to $1,920.

Some early participants encountered unexpected obstacles that prevented them from completing the program or being approved for licensure, Hudson said. Homeowners associations or landlords don’t allow participants to have child care centers in their homes, for example, or their homes don’t meet the standards set by the state.

Now, the organizers require them to take introductory courses to identify early challenges before starting the regular program.

“If they start going through it and everybody’s excited and then they realize, ‘Oh, I can’t even do this in my house, my landlord won’t let me,'” Hudson said.

One of the biggest challenges child care providers face is landlord licensing, Prow said. Many prefer tenants who do not have child care businesses, and in Oregon’s competitive housing market, they have many other options.

The accelerator runs in both English and Spanish, and the organizers say there was equal interest in both. Nine of the 32 participants completed the course in Spanish. Elix found out about the accelerator in a post on Facebook.

Damaris Elix of Bend is one of 16 Central Oregon residents who received funding to start their own child care centers through a business accelerator created by Central Oregon Community College and the nonprofit NeighborImpact. Photo by Damaris Elix.

Elix got her teaching credential in Guatemala and had been teaching some Spanish classes in the Bend area, but she was nervous about starting a formal business. The classes taught Elix more about insurance and liability, she said. She learned which forms to fill out and the formal rules for managing a child care center. The program has given her confidence.

By offering classes in Spanish, program organizers are supporting the local Hispanic community, Elix said.

“In my view, they are supporting a better future for us,” Elix said. “You can have a higher income with your own business, which gives you better opportunities in life. That’s the value[the program]provides: people want to grow.”

The dummy house currently has two students enrolled, Elix said, but she expects that number to grow after summer break. She provides after-school care where English speakers learn Spanish when school starts and children from Spanish-speaking homes strengthen their skills.

Elix is licensed to care for up to 10 children in her home. If she ever got to that point and wanted to expand her path, Elix knew where to turn for help.

Central Oregon Community College and NeighborImpact plan to build their program with an $8.2 million grant the Legislature awarded to NeighborImpact, Prow said. The plan is to help 60 other Central Oregon child care providers, who will each receive $5,000 for their businesses, and to accelerate parallel development for larger child care centers.

Betschart said Central Oregon Community College is working as a model for a program other Oregon community colleges and state universities can adopt to help their own communities.

But the speed bump alone won’t address Oregon’s child care needs, Betschart said.

“What we’re doing is not solving world hunger, it’s just feeding a few people for lunch,” he said. “When I think about the bigger picture, this is one small step toward where we need to discuss and invest more than we do today.”

This story comes from a partnership between The Oregonian/OregonLive and Report for America. Learn how you can support this critical work.

Sami Edge covers higher education for Oregonians. You can send her comments or story ideas at sedge@oregonia.com.

[ad_2]

Source link