[ad_1]

At 2am on the morning of May 11, Thomas Lauria poured himself a glass of Jack Daniel’s even though he was still at work. A partner in the Miami office of law firm White & Case, Lauria had spent the previous 15 hours overseeing a tense auction between two rival private equity consortiums for Hertz, the bankrupt rental car group.

Dozens of financiers, lawyers and bankers had descended on the White & Case office overlooking Biscayne Bay — for many it was their first in-person business meeting in 14 months.

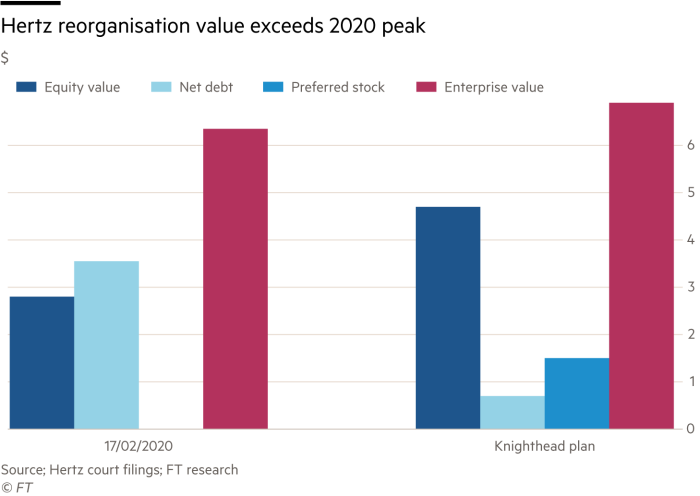

Fortified by what he later described as “the right mix of caffeine, sugar, carbs and whiskey”, Lauria eventually asked each bidding group to submit their “best-and-final” offers so a winner could be crowned and everyone could finally get some sleep. The bidding war that had built up over the previous two months pushed Hertz’s enterprise value to a figure approaching $7bn — a figure that was unthinkable a year before.

The remarkable turnround in Hertz’s fortunes mimics the dramatic rebound that large parts of the global economy are experiencing. When the rental car group filed for bankruptcy in May 2020, after business and leisure travel had ground to a halt, the company was the most high-profile victim of the economic carnage being inflicted by the pandemic — and seemingly portended more corporate failures to come.

Last June, Hertz somehow became the original “meme” stock — stricken companies which found frenzied support on social media among groups of retail investors whose confidence in their short-term futures was dismissed at the time as foolish by professional investors.

Yet by the spring of 2021, those terrifying early days of the pandemic were just a faded memory. Massive intervention, first by the Federal Reserve and then by the Treasury, stabilised the US economy. And then America’s furious pace of vaccinations buoyed hopes for the travel industry, allowing cruise companies and airliners to raise billions of cheap capital from flush institutional investors.

Thirty-two hours after the bidding first started, a group led by distressed debt fund Knighthead Capital prevailed in the auction. Knighthead’s group agreed a deal that gave Hertz an enterprise value of $6.9bn — including $1.1bn to a group of shareholders which, once dominated by day traders on the Robinhood app, now included a set of canny hedge funds.

Bankruptcy typically involves vultures fighting for scraps. Instead, the Hertz brawl revolved around a once broken company that was getting more valuable by the minute — the perfect metaphor for an upside-down year on Wall Street.

Braking fast

In late March 2020, as the full impact of the pandemic became apparent, Hertz faced dual existential problems. First, as travel halted, the group’s revenues had collapsed. In April alone, turnover was down by 73 per cent. More critically, the company’s fleet of more than 500,000 cars was financed off-balance sheet through special purpose vehicles. Since cars served as collateral, it was a relatively cheap way to borrow.

These lenders, however, also had negotiated protections where, if used cars declined in value, Hertz itself was obliged to inject equity into these SPVs. In April, with used car prices plummeting, bondholders told the company it owed them more than $100m. Rather than pay, the company chose bankruptcy. Carl Icahn, the billionaire investor who had been Hertz’s de facto boss, sold his 38 per cent stake on the eve of bankruptcy, registering a near $2bn loss.

Hertz’s hope was that through a court-supervised process there would be a way for the company to efficiently deal with all of its problems. Bondholders in its asset backed securities were, understandably, desperate to be repaid. And with the travel shutdown expected to continue indefinitely, there were even whispers that Hertz would be forced to simply liquidate its entire fleet.

That bankruptcy process centred on Lauria, a top corporate restructuring lawyer who specialised in representing long-shot creditors who needed a bulldog to argue their case in court. (His business card boasts the motto, “WALK IN. FUCK SHIT UP. WALK OUT”). The owner of a mansion on exclusive Fisher’s Island, Lauria had used his Miami base to become friendly with various Florida business luminaries, most notably Icahn.

White & Case had been working with Hertz for years and was the easy selection for the Florida-based company as it entered bankruptcy. This case, however, would require both more diplomacy and creativity than Lauria’s trademark bomb-throwing.

A chance for an outside-the-box gambit came within days of Hertz’s May 24 bankruptcy petition. The company, bizarrely, was becoming the hottest stock on Robinhood. Lauria and Hertz figured it was worth trying to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in cheap bankruptcy financing by selling stock. The bankruptcy court agreed at a Friday afternoon telephone hearing in June. But just as the company started gradually selling new stock — reaching $29m — the US securities regulator raised doubt and the company backed off. Instead Hertz was forced to take a $1.65bn loan with an interest rate approaching 10 per cent.

‘Perfect scenario’

Those look like V-shaped projections, Andrew Glenn thought to himself. By early 2021, the world seemed like a brighter place and so did the recently-created Hertz financial forecasts examined by Glenn, a veteran bankruptcy lawyer who was at that point uninvolved in the case. The figures showed Hertz operating profit jumping by a factor of seven between 2021 and 2023. Armed with the data, Glenn and an ally, Pericles Capital, quietly began approaching funds who might also believe that existing Hertz shareholders, once left for dead, could now witness a decent recovery.

In early March, Lauria had just signed up a deal based on those projections with two investment firms, Knighthead Capital and Certares, that gave the company an enterprise value of $4.9bn. Even that figure seemed miraculous given the events of the previous year. In the latter half of 2020, Hertz had agreed with the ABS holders to sell 200,000 vehicles. The prospects for a Covid-19 vaccine then were promising but a recovery in travel remained uncertain.

Still, Knighthead and Certares, the latter a travel specialist with stakes in TripAdvisor and the American Express travel agency, were leading a deal that would inject $5bn into Hertz. The company’s junior bondholders would realise a recovery of either 70 cents on the dollar in cash or get the chance to buy into the equity of new Hertz. However, Hertz shareholders, according to the terms, were to get nothing.

“This was the perfect scenario, I just needed a couple of good bounces,” says Eric Parkinson, a retail investor who likens himself to George Soros and Warren Buffett. Parkinson, based in Los Angeles, started speculating in Hertz shares around the time Knighthead/Certares terms were announced. “I love the intersection of fear, a lazy media narrative, and where nothing makes sense,” he says, referring to the mainstream view that anyone buying Hertz stock was a sucker.

Parkinson, like the hedge funds that lawyer Andrew Glenn was pitching, noticed that Hertz bonds had jumped well over the 70 cent offer on the table. The implication was that the company’s equity would soon start to be worth considerably more. Parkinson would accumulate 67,000 shares at an average price of below $1. And another private equity group was about to jump into the fray.

Let battle begin

The near $5bn that Knighthead had agreed to pay for Hertz seemed cheap to many. As such, another set of heavy hitters was ready to put up a fight. Tom Dundon knew a thing or two about automobiles. Dundon had become a Texas billionaire making subprime auto loans to Americans, eventually selling his business to Santander. Now he had teamed up with two elite private equity firms, Centerbridge and Warburg Pincus, to put in their own bid for Hertz predicated on a partnership with Carvana, an online used car marketplace whose public market capitalisation had surged to $47bn. By mid-April, Hertz had changed its mind and approved a $5.5bn bid from the Centerbridge/Warburg/Dundon consortium.

Through the course of April, the Knighthead and Centerbridge groups fought to win control of Hertz. Lauria, at the same time, wanted the company out of bankruptcy by July. To avoid an endless tit-for-tat, the court agreed to an auction for Monday, May 10 that Lauria had proposed.

The result was a late spring pilgrimage of Hertz bidders to Florida. “Why are we doing this in Miami?” one lawyer emailed to the group, incredulous that 95 per cent of the case participants lived in New York. Still, less than an hour after gathering at the White & Case office, virtually everyone had shed their masks, betting that their colleagues had already received a vaccine.

The duelling private equity groups had by now gathered critical allies. The Centerbridge team had secured the support of virtually all Hertz junior bondholders, which included the likes of Fidelity, JPMorgan and DE Shaw. These bondholders, holding $3bn of paper, were willing to take their recovery in new Hertz shares and were also purchasing more equity to fund the restructuring. These creditors had early in the process offered to buy Hertz at a $3.5bn enterprise value but now were hoping to tag along with the Centerbridge bid at a number near twice that figure.

Joining the rival Knighthead group was Andrew Glenn’s committee of hedge funds, which had bought up shares and were committing hundreds of millions in new capital. The group had also secured the heavyweight, Apollo Global Management, which was contributing $1.5bn of preferred stock. In the days leading up to the Miami showdown, the Knighthead team had seized the upper hand, offering roughly $300m to existing shareholders or $2 a share.

When the group gathered mid-morning on May 11, one banker described the vibe as “exhilarating” — a bidding war occurring live after a year of Zoom fatigue, even if the scene mostly involved long periods of sitting around with occasional moments of frenzy. Each side’s bids were complex, involving packages of cash as well as ownership in the new Hertz in the form of other complex instruments. Hertz’s bankers at Moelis & Co had to run the numbers through their spreadsheets before all sides would gather to hear the announcement that a bid had been deemed superior.

By midnight, only a couple of rounds of bidding had finished. The Knighthead group was able to quickly counterbid. However, the Centerbridge group proved messier, requiring the unwieldy bondholder group’s consent before sending in a bid. Jim Millstein, the restructuring banker representing Knighthead, sent a flurry of heated text messages to William Derrough of Moelis about the perceived leniency extended to Centerbridge. At one point late at night, Lauria had an agitated argument with a Certares executive.

“Lauria thrives in the chaos,” explains one bankruptcy adviser who was in the room, adding: “As long as he is controlling the chaos.”

Still, as Lauria sipped his scotch in the small hours he knew that however erratic the process had been — each bidding group was convinced that Hertz had been prejudiced against them over the previous months — he had essentially done the unthinkable in stoking up a hot auction. By midday on Tuesday, as the White & Case office reeked of Papa John’s pizza and Cuban sandwiches along with dozens of weary bidders who had not left the premises in 24 hours, Hertz told the two groups to submit their “best and final offers”.

Each side was approaching their limit, but no one wanted to lose by a penny either. Ultimately, the margin was not close. Centerbridge offered a package worth $5.39 cents a share or $841m in the form of cash, options and preferred equity. Knighthead submitted a final bid they said was worth $1.15bn or $7.36 a share.

While that included a cash payment of $239m, more than $700m was in options derived from the Black-Scholes equation. The Centerbridge group was furious, believing Knighthead had goosed that figure by using financial inputs in their bid that defied economic reality. Still, members of the Centerbridge group admitted that its marriage with the bondholders had limited their own agility.

Overall, Hertz accepted a deal had raised $7bn in new capital, its overall enterprise value had doubled to $6.9bn in three months and all its creditors would be paid 100 cents on the dollar and in cash. Eric Parkinson, the retail investor who had loaded up shares as the bidding war began, was sitting on winnings of $400,000.

Late that Tuesday, some of the bidders headed back to New York having never checked into their hotel — one banker described the ordeal as “inhumane”. Members of the Knighthead group retreated to a celebratory dinner at a nearby Italian restaurant, Il Gabbiano.

On Thursday, the court approved the restructuring which is set to take effect in a few weeks. Hertz shares now trade at $7, implying a market capitalisation of more than $1bn.

“These guys paid a pretty penny,” says one person involved in the Centerbridge bid. Analysts at research firm CreditSights argue that the winning bid requires “everything to go right and lot of conviction on the forward variables”, citing not just the recovery in travel but both high rental car rates and used car prices.

Jim Millstein, the banker for Knighthead who remains irritated by the auction shenanigans, still tipped his cap to the man who had orchestrated the process, “Lauria, as much as it pains me to say it, was maybe both smart and lucky.”

Lauria, for his part, acknowledged both the challenge and the satisfaction of the Hertz case. “I got to use every braincell I have and every skill I’ve used over 35 years,” says the 60 year-old. “Hertz called it all into play.”

[ad_2]

Source link