[ad_1]

From fashion weeks in Dakar and Lagos, African designers are having a blast at South African Thebe Magugu’s Paris runway shows. Here in America, designers Busayo, Telfar, and Hanifa infuse their collections with beauty from their native countries of Nigeria, Liberia, and Congo.

While many Western consumers are now embracing African designers, a new exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London shows that Africa has always had an influence on global fashion. The grand exhibition titled “African Fashion” showcases the diversity of fashion in the 54 African countries.

But perhaps most interestingly, it shows how African designers are influencing the global fashion industry, from their sustainable practices to their aesthetic sensibilities. “We hope that the exhibition will give a glimpse into this rich scene, recognizing that African fashion designers are changing the fashion geography of the world,” said Elisabeth Murray, head of the project.

Christine Chesinska, the museum’s first curator of African and African diaspora fashion, describes the long history of African fashion in a comprehensive book accompanying the exhibition. She points out that Africans have always traveled through Europe and Asia, taking their fabrics, prints and imagery with them, which subsequently influenced local fashion around the world.

However, due to racism around the world, African fashion is often misrepresented, being labeled as archaic and portrayed as timeless. Otherwise, it is “a unique source of inspiration for the designers of the Global North,” writes Chesinska. (Consider how designers like Tory Burch and Stella McCartney have been accused of cultural appropriation.)

This exhibition sheds light on the history, complexity and diversity of African fashion, giving a better appreciation of the work of many talented designers from the continent and the diaspora. Here are four important aspects of African fashion history that help us contextualize the work of African designers today.

A strong fashion ecosystem has existed for a long time

Shad Thomas-Fahm isn’t a household name, but she should be. Born in 1933, she is sometimes referred to as Nigeria’s first fashion designer. At the age of 20, she landed in Britain to train to become a nurse, but began taking courses at St. Martin’s School of Art after seeing exquisitely dressed mannequins in London shops.

Returning to Nigeria in 1960, the country gained independence from Britain. At this critical juncture, she became one of the first modern African designers to set up a shop called Maison Shed and a factory in the Yaba Industrial Estate to produce her clothes. She is known for reimagining traditional Nigerian fabrics, patterns and colors and deliberately aligning her creations with Western notions of “couture”.

In the book, Czesinska Thomas-Fahm writes that she contributed to “the development of a fashion ecosystem directly informed by her experiences abroad”; This has set the stage for hundreds of designers who are now seen across the continent. Today, African designers use local crafts and workshops to make their clothes, and participate in fashion weeks modeled after European versions.

Five key fabrics drive the designs

Bold prints are key to African fashion. Talented, updated and mixed with contemporary African designers. Western brands and designers sometimes use them too, and it is accused of cultural appropriation. The exhibition showcases five different textiles that are the basis for contemporary African designers.

Wax Print

This cloth originated on the island of Java in Indonesia, but in 1846 Dutch traders tried to mass produce it in the Netherlands to sell back to the Javanese. However, the Javanese did not like the machine-made cloth, which had small cracks and spots on it. Therefore, the Dutch marketed the cloth in West Africa. There, locals admired the “imperfect” signs. This fabric is becoming popular in Africa and is central to the modern African aesthetic. Indeed, it is now made locally in factories across the continent, machines that have included places in the final designs.

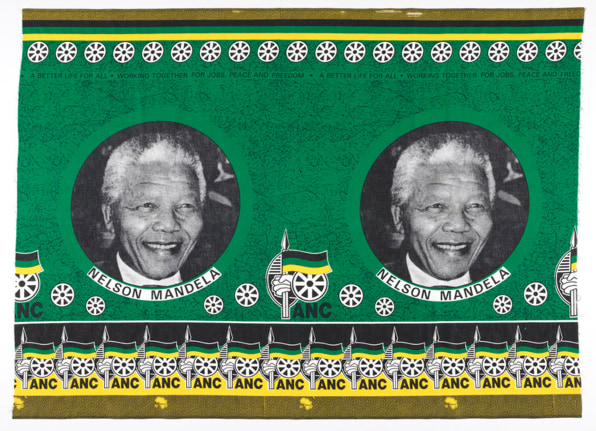

Memorial cloth

Across Africa, cotton fabric is printed in factories to commemorate important events, including the election of politicians. When Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black president, and Barack Obama later became America’s first black president, they each had their faces silkscreened onto a special commemorative cloth. These fabrics are seen as decorative items rather than clothing.

Banner

This is a distinct fabric from the Irros people of southwestern Nigeria and dates back to the 1800s. It is made by tying and dying the fabric in knots, creating elaborate, colorful patterns. It is worn by women as a wrap around their body, and included in men’s sleepwear. Adire’s popularity has risen and fallen over the years. In the first half of the 20th century, it was sometimes considered backward by the educated middle classes, but the fabric has come back into fashion among a number of young Nigerian designers, including Busayo, whom I profiled last year.

to the city

This cloth is associated with the Asante people of south-central Ghana. It is made of hand columns that gather narrow pieces of fabric together to create a large sheet of fabric that can be wrapped around the body. The fabrics sometimes contain complex geometric patterns that tell stories, representing birds, people and insects.

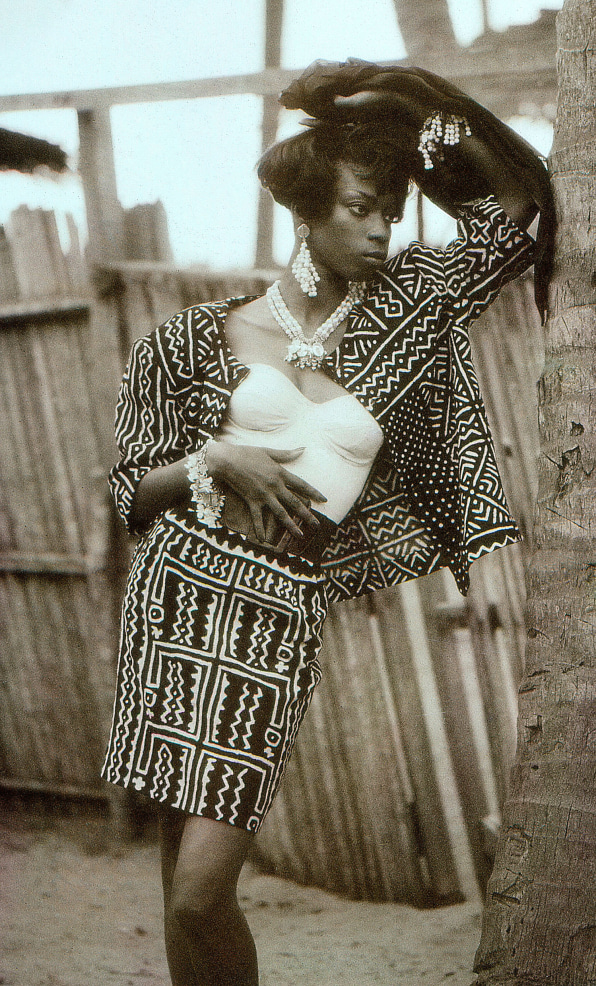

Bogolanfini

This fabric is made by the people of Mali and Burkina Faso and is especially associated with the towns and villages of Beledogo. It consists of hundreds of layers that are woven together to make dyed garments. Experts are not sure when it was first made, but in the 11th century, the fabric was used to make wraps for hunters and warriors, teenage girls and women. These garments are worn at important times in a person’s life, including marriage, childbirth, and burial.

Gender fluid fashion is in vogue.

As I have written before, many countries in Africa have conservative views on gender and sexuality. But there are also a number of designers who use fashion to push back against these stereotypes. For example, Nigerian designer Adebayo Oke-Lawal came up with the name Orange Culture ten years ago with the intention of creating a space for people like him who don’t want to be limited by traditional culture.

While blue is often considered “masculine” in the West, Oke-Lawal is drawn to orange on the blue color wheel. Orange culture clothing is gender-bending and androgynous. The menswear consists of matching pink suits and see-through gowns. Women’s clothing includes oversized boxy blazers. All designed to show how arbitrary and socially constructed notions of sex and sexuality are.

Here in the US, Telfar Clemens, first in Liberia, does the same thing. He wants to push back against traditional gender norms by creating unisex clothes. His latest Telfar collection features asymmetrical one-shoulder tops in pink and orange, which are worn by both male and female models. And his iconic handbags are carried by both sexes.

Sustainability is paramount.

For decades, Africa has been a dumping ground for fashion waste from Europe and the U.S. When Western consumers donate clothing to charities like Goodwill, more than 80% of it is unsold and sent to African countries for resale. Ultimately, however, most of it ends up in landfills in those countries.

Africans have long seen the extent of the world’s fashion waste, and this new generation of designers informs how it works. In the year Take Ghanaian designer Kofi Ansah, who was born in 1951 and died in 2014. Ten years ago he created collections for Saks Fifth Avenue and Milan retailers, but focused on producing in a way that didn’t create waste.

Instead of relying on wasteful global fashion supply chains, he founded a weaving center encouraging young people to create textiles locally in small factories. Many of today’s young designers follow in his footsteps. For example, Busayo opened a small factory in Nigeria, creating clothes in small batches, so there is no overproduction.

[ad_2]

Source link