[ad_1]

Ayo and his wife left their friends’ house in Akure early. They had received a warning that bandits had attacked somewhere along the two-hour stretch of rural highway home, and they wanted to get there before dark. Just over an hour into the drive through southwestern Nigeria, they crossed a police checkpoint where officers and vigilantes milled around the site of the earlier attack.

They drove a few minutes further along the road before two cars ahead of them began to slow down. Around 15 young men emerged from the bush, spaced around 10 feet apart in a long line down the highway, shooting pump-action rifles into the air and screaming at the motorists.

Ayo pulled his car on to the shoulder of the road but kept his engine idling and his windows up. As the bandits approached the dozen or so cars behind him, he whispered to his wife. “Are you ready?” he says, motioning for her to duck. He slouched too, and slammed his foot on the accelerator to get past the one unarmed bandit in front of him.

“I was not just scared, I was in serious shock — I thought about my three kids, who were supposed to travel with us . . . it was a horrific day,” says Ayo, 39, who asked not to be identified further for fear of reprisal. “You never saw this in the south-west before . . . [but] over time bandits have seen that this is a good business, that this is a good way to make money.”

On that Sunday in mid-January, Ayo and his wife narrowly escaped joining the thousands of Nigerians who are kidnapped each year from highways and villages across Africa’s most populous country by gangs of armed men known colloquially as bandits. The other motorists were not so lucky — Ayo heard later that some of them were abducted.

A combination of explosive population growth, rampant unemployment, underfunded and incapable security forces, and easy access to small arms has made banditry a booming industry in a struggling economy, and Nigeria’s most serious security threat.

“Sadly the kidnapping industry is thriving across Nigeria,” says Aisha Yesufu, a social justice activist from the north of the country. “We are in a situation in Nigeria where people who ordinarily would enter normal society, would work, they do not have any hope for anything. Instead they . . . go and kidnap people [to] make money.”

The economic picture in Nigeria is dire. Population growth was outstripping that of gross domestic product even before the pandemic sent Africa’s biggest crude oil producer into recession. Food inflation has hit a 15-year high, while unemployment is rampant — over half of Nigerians are under- or unemployed; for young Nigerians, the bulk of the 200m population, the figure is two-thirds.

Ransom payments that can range from a few hundred US dollars for ordinary citizens to reportedly six figures for high-profile victims are an attractive incentive to organised crime syndicates and young men lacking opportunities. To get loved ones back, family members generally pay the ransoms in cash though sometimes bandits ask for some of the payment in the form of phone credit.

“Once word goes out that you can kidnap people and get ransom, why wouldn’t you go and do it?” asks Amaka Anku, African director for Eurasia Group. Massive ransom payments made to Islamist militants Boko Haram for the return of some of the 276 Chibok schoolgirls kidnapped in 2014 helped set the stage, she adds.

Beyond the lack of economic opportunity, she says, “the proximate cause of this is this mixture of perverse incentives [it pays well] and a complete incapacity to police”.

Deadly business

The constant pattern of violence, and the way it has impinged on the average Nigerian’s everyday life — from travelling to visit relatives to moving goods across even short stretches of highway — has severely damaged President Muhammadu Buhari’s national security credentials and revealed a woefully underfunded and mismanaged Nigerian military and police force.

The banditry crisis is also exposing raw ethnic tensions which are never far from the surface in Nigeria. The bandits are largely thought to be made up of members of the Fulani ethnic group who are mostly nomadic herdsmen and also Hausa farmers, whose communal clashes with sedentary farmers have sparked violence for years. That has caused some, particularly in the mostly Christian south, to accuse Buhari, himself a Fulani, of going soft on banditry.

Unlike previous abduction crises, the wave of kidnappings sweeping Nigeria is not isolated to the Niger Delta — as it was 15 years ago, when oil workers were routinely snatched — or the north-east, where Boko Haram made international headlines in Chibok seven years ago.

Two large school abductions have occurred in just the past few months — more than 300 boys from a facility in Buhari’s home state Katsina in December and roughly the same number of girls from a secondary school in neighbouring Zamfara in February. Both groups of children were returned and the government insists that it did not pay a ransom. But the bodies of three of the 23 students abducted from Greenfield University in Kaduna last week were found shot dead, according to a statement by local authorities on Friday.

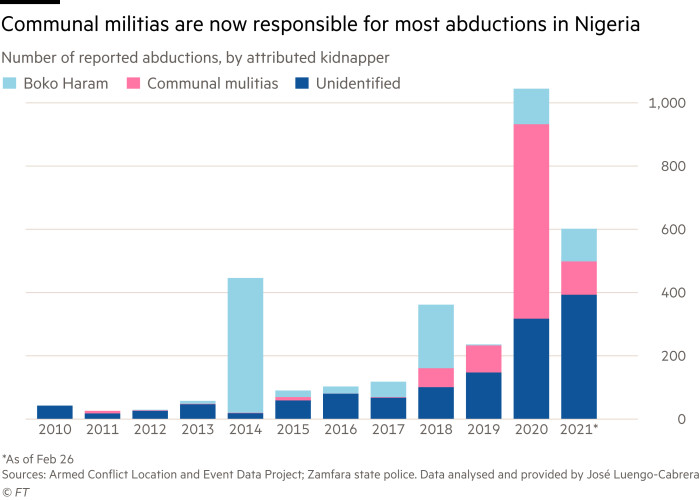

Smaller mass kidnappings — a busload or a household of people — now routinely occur in every corner of the country. The number of people abducted last year — estimated at nearly 1,100 — is more than double the amount kidnapped at Boko Haram’s height in 2014, according to data compiled by security analyst Jose Luengo-Cabrera. The figures, culled from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, are the closest to official data available, and “should be taken as indicative” but are “likely to suffer from serious under-reporting” compared with the true total number of abductions, he says.

Nearly as many people — 2,690 in 2020 — are now being killed in the north-west of the country, the heart of the bandit crisis, as in Boko Haram’s stronghold Borno state, where 3,044 civilians were killed. The violence has displaced hundreds of thousands of people in the north-west.

There has long been speculation that some bandits in the north-west are working with Boko Haram. Whatever the crossover, the bandits are achieving one of the Islamist group’s signature causes — the eradication of western education in the north of the country. Since criminals began targeting schools, northern governors have shut down hundreds of institutions that not only provided education to a neglected population but also acted as important buffers against child marriage. That’s changing now, says Yusuf Anka, a security analyst in Zamfara, a northern state at the heart of the crisis.

Three of his nieces were among 279 schoolgirls kidnapped from Jangebe village in February. They have since been released.

“Somebody said that only over his dead body would his child [now] go to school,” says Anka. “300 children were taken into the forest . . . [parents say they] are not stupid enough to send them back there.”

Failing security forces

The banditry crisis is widely thought to have originated in clashes between farmers and herders over land in northern Nigeria. Nomadic herdsmen were pushed off historic grazing territory — sometimes violently — as it became farmland. They encroached, sometimes aggressively, triggering a vicious cycle of tit-for-tat reprisals that eventually escalated into village massacres and mass kidnappings, as erstwhile cattle rustlers realised there was money to be made in stealing people.

Banditry has flourished in an economy that has been crippled by two recessions in six years. It has spread across the entire country partly because it has become a viable career option for some of the millions of young Nigerians thrown each year into an economy that cannot create enough jobs to accommodate them, says Zainab Usman, Africa director for the Carnegie Endowment for Peace.

“There is indeed urgency on policymakers and also Nigeria’s development partners to really think about supporting initiatives that increase productivity that help business grow so they can create new jobs,” she adds.

For now kidnapping remains a career path because there are virtually no consequences for doing it, says Chris Kwaja, senior lecturer at the Centre for Peace and Security Studies in Yola, a city in the country’s north-east.

“You will see instances of groups arrested by security agencies but in all these arrests we haven’t seen prosecutions . . . so we see how they are emboldened,” says Kwaja, adding that under-resourced security forces rife with corruption are incapable of addressing the problem.

The president has essentially conceded that the security forces cannot protect the country on their own. Buhari and his defence minister have both sought to put some responsibility for security on to the citizens themselves. “Our military may be efficient and well-armed but it needs good efforts for the nation’s defence and the local population must rise to this challenge of the moment,” he wrote on Twitter in March.

“That’s the reality,” says Anku, “but for the president to be coming out and saying that is nuts, because all you’re doing is saying to people you can’t trust us to protect you, better go get armed, and that’s what’s creating clashes.

“Once these guys get armed and then realise they can make some money with these arms, then you’re creating bandits,” she says. “It’s madness.”

The Fulani factor

Ayo and his wife were attacked in Osun, which, along with the five other southwestern states, announced in April that it would ban open grazing. The governors took pains to say they were not evicting nomadic Fulani herdsmen from the region.

“This is your home. You’ve lived here, married and done business with us. Nobody is going anywhere,” said Ekiti state governor Kayode Fayemi, according to local media.

But Anku says the announcement of the ban — and the showy rounding up of cattlemen who had violated it — was just political theatre. Open grazing had already been banned in some states. “Just that simple act created a whole series of violent events . . . which will create even more violent events,” she says.

She points to a fight in February between a Yoruba cobbler and a Hausa trader at a market in the southwestern city of Ibadan that erupted into full-scale ethnic clashes that killed roughly a dozen people, according to Reuters.

The violence came after weeks of escalating tensions, as local Yoruba leaders, a mostly southern ethnic group, accused Fulani herdsmen, closely associated with the larger Hausa group, of being violent criminals, calling for their expulsion from the state.

Abubakar Umar Girei, national co-ordinator of the international Fulani organisation Tabital Pulaaku, says many bandits are recruited by criminals because of “their ignorance and their illiteracy”, and that their actions are being used to stigmatise all Fulani, who are “no longer secure to walk out and pursue their legitimate business”. The ethnic group is common to many west African countries.

Girei says that despite criticism that Buhari favours Fulanis, things had never been worse for the ethnic group, which he says is perpetually characterised as “killer herdsmen” in the media.

“Most of the challenges they are facing are because the president is a Fulani man . . . that is why communities in the south are attacking Fulanis, and it’s unfortunate that the president himself doesn’t see it,” he says. “This government has never taken the issue of the Fulani people seriously.”

‘Treat criminals as criminals’

Buhari — a former military head of state who won the presidency in 2015 promising to secure the country from Boko Haram — has taken a hard line in recent months, at least rhetorically. The 78-year-old has said his government will not negotiate with the bandits, It has meant pushing back against some of his political allies in northern states who have tried to offer bandit groups amnesty and redress — including vehicles, money and pledges to build clinics and schools for their communities — if they lay down their arms.

Zamfara is one such state. Anka, the security analyst, says the impulse to negotiate is a good one, because many of the perpetrators have been abandoned by the state. “Dialogue is very very important [but] in Zamfara we see a dialogue that puts perpetrators above victims,” he says, which creates more incentives for bandits and sows resentment.

The president, like some of his political allies, has vowed to “treat criminals as criminals”. His office has released a series of statements in which he warns the bandits to cease or to prepare for the wrath of the security forces. He issued one such warning in mid-March, after dozens of students were abducted from a forestry college next to a military academy in Kaduna. “The country will not allow the destruction of the school system,” he said. A few days later, another group of bandits stormed a primary school, again in Kaduna, and made off with three teachers.

In March, the president ordered security agents to “shoot any person or persons seen carrying AK-47s in any forest in the country” and banned all mining activities in Zamfara, where the illegal hunt for gold is fuelling the crisis.

Zamfara governor Bello Matawalle announced that 6,000 troops would be deployed to root out bandit camps in the sprawling, largely ungoverned Rugu Forest. He also banned more than one person riding on a motorcycle, the bandits’ vehicle of choice. But many observers pointed out that it is also the main means of transportation for many Nigerians, and previous bans have failed.

Aliyu, a 31-year-old unemployed worker from the agrarian Niger state, which has been severely hit by the wave of banditry, says he has been told since he was a child about the urgent need to tackle youth unemployment.

“They’d say, if you don’t arrest unemployment and idleness among the youth, you are sitting on a time-bomb — as far as I’m concerned, that time-bomb is upon us now,” he says. “Old men don’t carry guns and stand on the roadside and kill or kidnap people — it’s young people who do these things . . . what’s at stake here is the security of the country.”

[ad_2]

Source link