[ad_1]

It would buy you a year of study at Harvard University, a couple of luxury boxes at the Yankee Stadium in New York or a lengthy stay at London’s Ritz Hotel. But Chinese citizens might soon be able to do something different with the $50,000 they are permitted to take out of the country annually: invest it.

In February, Ye Haisheng, a Chinese official at the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (Safe), said the government was researching whether the allowance — which has been unchanged since 2007, requires no specific approvals and is spent mainly on travel and education — could also be used to purchase overseas securities and insurance.

Even as it has risen as an economic power, China has retained strict capital controls which keep most of its vast household wealth within its borders and reflect the control which the ruling Communist party continues to wield over the country.

This year, there are more signs than ever of that grip on savings loosening. As well as a potential change to the allowance, the government in June approved record amounts of money to flow out of the country through an official investment quota. It is also on the verge of launching a programme with Hong Kong, called Wealth Connect, that will allow households in southern China to invest overseas.

“This is a very interesting time for all of us,” says Terry Pan, chief executive officer for Greater China at Invesco, which is eligible to manage money through the programme. “Liberalisation is happening in front of our eyes.”

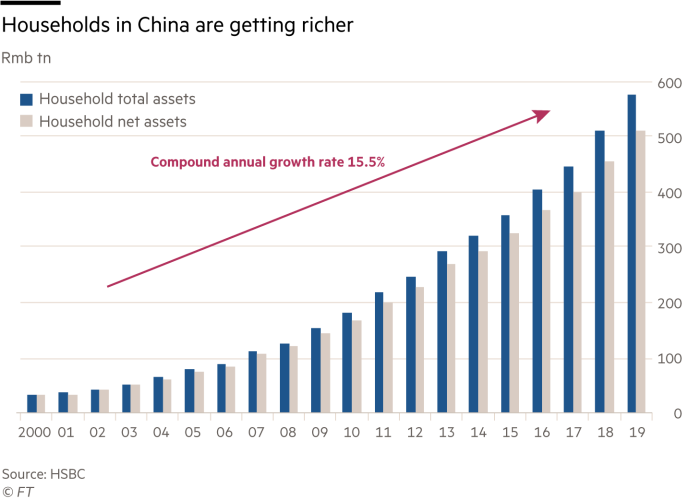

While China’s asset management outflows remain small, they are part of a profound shift that hints at future expansion. The country’s wider financial system is opening up, enticing the world’s biggest banks and asset managers. HSBC, one of the most active participants, estimates that Chinese households will have Rmb300tn ($46.3tn) of investable assets by 2025 — an amount equivalent to the entire US bond market.

“With more outbound investment channels available, households have genuine choices to diversify into overseas securities,” the bank noted in May.

In the past, outbound schemes have been suspended at times of market volatility while other projects have proved to be false dawns, adding to the sense that for now China is unlikely to loosen its capital controls, except at the margins.

The economic logic of keeping so many savings trapped in one place, however, has come under greater scrutiny at a time when the renminbi has strengthened markedly and the stock market in February surpassed its 2007 peak. Policymakers have become more vocal, warning of rising asset prices, especially within the country’s property sector where much of household wealth continues to chase returns.

If it were allowed to suddenly chase returns globally, that could have chaotic consequences from both a Chinese and western perspective. The country’s savings would have the capacity to flood certain international markets — if a mere 10 per cent of households invested $50,000 abroad, HSBC calculates, that would amount to $2.4tn. Michael Every, global market strategist at Rabobank, says “carrots had been dangled” in front of western banks but a deep opening of the capital account was “structurally extremely unlikely” because it would lead to a collapse in asset prices within China, as well as the value of its currency.

But China’s policy shifts can be almost imperceptibly gradual. Just as the country’s entry into the World Trade Organization two decades ago has resonated in all corners of the global economy, even the slim prospect of capital account liberalisation raises urgent questions for the entire financial system: will Chinese savings be unleashed upon the world, and what happens if they are?

Investing by the back door

In 2016, the central bank, the People’s Bank of China, prohibited the use of so-called “dual currency” credit cards that allowed people in China to make foreign purchases through international networks Visa and Mastercard. Unionpay, the country’s major credit card provider, was barred from being used to buy insurance in Hong Kong.

The ban came after mainland citizens began taking out life insurance policies in Hong Kong that were linked to savings policies. When the policies matured, the customer was left with a lump sum in Hong Kong dollars, effectively circumventing the $50,000 currency limit.

“At the time you could use a mainland credit card to pay for anything in Hong Kong,” says Stewart Aldcroft, Asia chair of Cititrust, an arm of Citibank. “The regulators suddenly woke up to that and had to do something about it.”

Like the casinos of neighbouring Macau, Hong Kong is well known for its role in illicit flows of money out of mainland China, ranging from bags of cash to manipulating trade invoicing figures. But the territory — which has undergone extraordinary political upheaval in the past two years — now offers up a greater than ever array of legitimate methods for investing money outside mainland China.

The Wealth Connect programme is set to be the most symbolic milestone yet in consolidating Hong Kong’s role as the gateway to international markets. A pilot scheme, expected to be launched this year, will allow households in nine Chinese cities in the Greater Bay Area — which includes Shenzhen and Guangzhou and is home to about 70m people — to invest up to Rmb1m ($154,000) in low and medium-risk funds domiciled in Hong Kong. It stands to give them access to markets in the US and elsewhere.

Offshore investors can also buy mainland products through the scheme, which follows previous programmes linking Chinese stock and bond markets to Hong Kong. Eddie Yue, head of the city’s monetary authority, says the programme “underpins Hong Kong’s strategic importance in the mainland’s opening up of its financial markets”.

Wealth Connect nonetheless represents a cautious approach from Beijing that applies to other methods of investing abroad legally. Crucially, it operates according to a closed-currency loop, meaning investors in the country have to convert the proceeds back to the renminbi when they cash out. Total flows in each direction are capped at Rmb150bn ($23.1bn) — a tiny fraction of household wealth.

“Wealth Connect will be the first time that China has legitimately allowed mainland residents to directly move money out of the country for the purposes of offshore investment,” says Anthony Lin, Standard Chartered chief executive for the Greater Bay Area. “Today the limit is not very big and there are restrictions on products, but we believe this will change over time.”

For international banks, the Wealth Connect scheme is just one part of a China savings opportunity, most of which will be managed within the country itself. In February, HSBC said it would spend $3.5bn over five years to develop its wealth and personal banking operations in Asia, which already accounts for two-thirds of its global wealth business. Citibank and Standard Chartered have laid out similar plans that aim to double wealth management staff numbers and income in mainland China and Hong Kong over the next five years.

“The opportunity is enormous,” says Greg Hingston, HSBC’s head of wealth and personal banking for Asia Pacific. “Even if you only get a small share of it, it’s going to be very meaningful.”

Despite excitement over Wealth Connect, data from Bloomberg Intelligence estimates the total annual fees shared by banks operating under the scheme is likely to be less than $500m due to the initial cap.

For foreign players, part of the bet is instead that a gradual loosening of constraints on that growing wealth will gather pace. Major US banks that have partnered with Chinese counterparts have also emphasised the offshore opportunity, where they have a distinct advantage compared with onshore competitors; Goldman Sachs plans to eventually offer “overseas products” — although it has yet to say which ones — through its partnership with ICBC.

“[International] banks aren’t looking at what direct income can be generated in the short term,” Lin says. “We are focusing on building a customer base so that over time, when China further opens up its capital account, the relationship with those customers gets far bigger.”

The urge to invest

Warren Jia, a 29-year-old IT worker in Shanghai, studied at Glasgow university in Scotland and still has a few thousand pounds in a UK bank account. He says overseas investment is something he is actively pursuing.

“First of all I don’t want to put all my eggs in one basket,” he says. “The second is I had experience living abroad and there’s a possibility of immigration, or living and working abroad in the future, so I think it’s necessary to hold some assets overseas.”

Savers like Jia are not only an opportunity for foreign and domestic businesses seeking to take advantage of a booming asset management industry. They are also an opportunity for the Chinese government as it grapples with a strengthening renminbi and a rush of inflows into its stock and bond markets encouraged by its rapid recovery from the pandemic.

In June, the government increased to $147bn the total quota for a scheme that allows companies to invest overseas on behalf of their clients, the majority of which are retail investors. The additional $10bn was the largest increase in the 14-year history of the Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor scheme. Like Wealth Connect, it forces investors to cash out in renminbi, meaning it currently has no clear use for those wishing to spend, rather than invest, overseas.

Analysts suggest the move was partly a response to the strength of the renminbi, but also hinted at its relevance to the debate over the future of China’s capital account, one which relates not only to household savings but also overseas activity from the country’s businesses, financial sector and the government itself.

“I would say that in typical China fashion this is going to be a trial and error approach,” says Carlos Casanova, a senior economist for Asia at UBP. “There are reasons for and against doing this.”

Asset bubble territory

After Deng Xiaoping reformed China’s economy in the late 1970s, direct foreign investment rushed into the country. Capital outflows were tightened after the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, which exposed the risk of foreign money being rapidly pulled out of emerging economies. The QDII scheme was launched in 2006 and has been followed by incremental signs of further liberalisation, the latest of which is Wealth Connect.

A 2017 book published by the IMF said opponents of liberalisation typically cited the Asian crisis, while proponents pointed to “self-fulfilling expectations of currency appreciation and bubble-prone domestic financial markets”. Foreign direct investment in China last year at $163bn surpassed inflows into the US for the first time.

This year, official expressions of concern over inflated domestic asset prices have become more frequent. In March, Guo Shuqing, China’s top banking regulator, warned of “bubbles” within the country’s property sector. The government has moved to restrain leverage across the biggest real estate developers, but property prices have continued to skyrocket.

While these factors might on the face of it encourage outflows to ease pressure on prices, they might also discourage an opening of the floodgates. “In the long term full capital account liberalisation will only take place once all of the domestic structural fragilities . . . are resolved,” says Casanova, pointing to “high corporate debt levels” as the biggest issue. Guo in March not only warned about domestic property but also bubbles in the same “foreign markets” where Chinese savers would be more active.

Dariusz Kowalczyk, an economist at Crédit Agricole, suggests full liberalisation is unlikely because the government will “want to continue to micromanage the economy”, so they will need “to retain capital controls and exchange rates rather than being thrown at the vagaries of the global system with all its volatility”.

China’s position is nonetheless highly unusual, and is likely to become even more so as its middle class expands. HSBC estimates it will soon exceed 500m people. The IMF book said it was “difficult to imagine that one of the world’s largest economies and trading nations will maintain tight controls on capital flows indefinitely as it becomes an upper-middle-income economy”.

A Safe official in June said the QDII expansion was “conducive for meeting domestic investors’ needs for diversifying overseas asset allocation”. China holds more than $1tn of US Treasuries, which help it control its exchange rate, but capital controls will also need to be relaxed if it is to achieve its stated goal of internationalising its currency.

Experiments in capital account liberalisation are an opportunity for foreign asset managers and Chinese investors. Across international financial markets, though, outflows could have significant and unexpected consequences.

Overseas corporate activity or purchases from wealthy individuals with income streams abroad have already helped reshape the overheated housing markets of entire cities in the west, from Vancouver to Sydney.

The first phase of the Wealth Connect scheme only allows savers to buy low and medium-risk products such as highly rated bonds, reflecting the government’s cautious approach. Pan at Invesco suggests that under a hypothetical scenario with all of Chinese savings flooding into low-risk products, “you would obviously see even more negative interest rates” as the purchases of bonds would push up prices and move yields lower.

The $23bn total through the Wealth Connect scheme will not move global markets, but if Beijing is laying the groundwork for further reform, that cap could change in time.

Citi’s Aldcroft notes that hundreds of millions of people in China have already bought into some form of domestic mutual fund, which he says are currently more than 99 per cent targeted towards the domestic markets. Diversified investments overseas — the kind that help build stable retirement systems and insurance markets — would continue a long-term pattern in which the Chinese middle class flocks to buy the staples of its western counterparts.

Its policy approach, though, is equally liable to change course despite its gradual trajectory. “Ultimately everything about China is about control, keeping control, maintaining control,” says Aldcroft. “And it’s not going to let things get out of control.”

Additional reporting by Wang Xueqiao in Shanghai

[ad_2]

Source link