[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to receive the newsletter directly in your inbox every day of the week

It’s the end of Unhedged’s first week. How’s it going? Email me: Robert.Armstrong@ft.com.

QE and stock prices (second part)

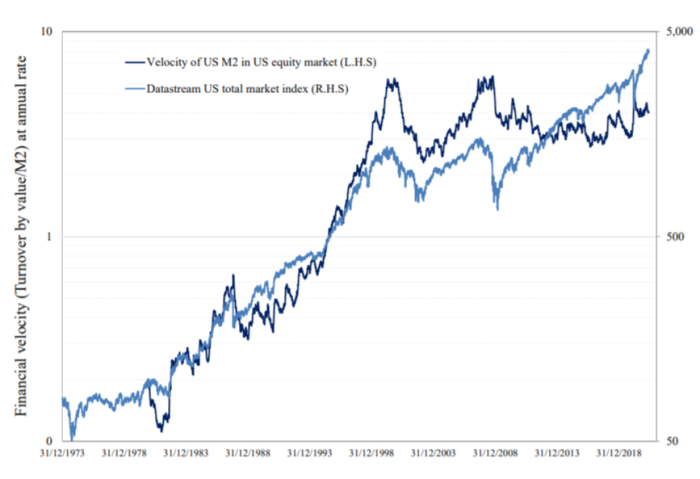

Here are two lines that mostly go up and to the right:

The two lines are M2’s money supply (cash, deposits, money market accounts) and the S&P 500. M2 is rising rapidly due to quantitative easing: Fed buys cash, putting money us. It’s less clear why the S&P is rising so fast. The fact that the two lines have recently merged encourages a popular causal story: “the Fed prints money and has to go somewhere and go to the stock market.” A couple of days ago me pointed out that these causal stories are incorrect, because cash is not transformed into actions. When I buy shares, the seller gets the cash. It’s not “in the bag”.

What is really happening is that all the extra money they are reducing is making people want it less, relative to stocks, and rising relative demand for stocks is forcing prices to rise. This is how QE affects stock prices (or in a way that it does; other people, especially central bankers, prefer stories about QE to reduce the discount rate, over which rather).

Eric Barthalon, global head of capital markets research at Allianz Research, notes that this process is self-limiting. As stock prices rise, the weight of cash relative to investors ’portfolio equities drops to a level where investors are happy. Investors stop trading so much and prices stabilize. In this story, the Fed is not just filling the cash markets. There is an intermediate factor: the relative preference of investors for cash.

Barthalon’s argument – I find it quite convincing – is that (a) investors’ preference for cash is not stable and (b) the Fed is not in control at the times that matter, that is, when the markets are falling. You can track investors ’unstable preference for cash by observing the speed of money or how much it changes hands. Barthalon told me:

“It is not the amount of money, but its circulation, which causes asset prices to rise or fall. . . and historical experience shows us that central banks do not control the speed of money, especially in the capital markets. “

We now see why central bankers may prefer the notion that with QE they control the discount rate that determines the value of stocks while keeping government bond yields low. Because that lever, in theory, will work even if investors suddenly decide they really like cash, which they do when markets fall.

Here is Barthalon’s long-term graph on the speed of money in the stock market (the value of daily market transactions divided by M2) relative to the value of the stock market. Watch the speed drop sharply as the market declines:

These two lines co-vary and relate to an ordered causal history. What can be taken away is that the large volume of money floating around cannot, on its own, keep the stock market high.

Armstrong’s Department is wrong: bitcoin

Yesterday I argued that bitcoin is best considered the equity of a company whose only asset is an unproven technology. This technology will be demonstrated when Bitcoin becomes money. But bitcoin is now not money because, even though people change it, it is not widely accepted as a form of payment, there are few transactions, transaction costs are high, and so on.

The most common response I received was that Bitcoin is not trying to be money. Money has two key properties. It is a store of value and a means of exchange. Most people who think I’m wrong think that bitcoin is about saving value. That’s why your finite supply is so important. If it’s a little expensive to operate, a little illiquid, etc., who cares. It is similar to gold and diamonds, commodities whose main feature is their rarity and value, not their ease of use.

I am not convinced. Gold and diamonds have uses in industry and jewelry, they have millennia of convention that support their preciousness. The only thing that supports Bitcoin as a store of value, as a precious commodity, is that it can be both a store of value and a above all a good means of exchange: which can trade extensively, without friction, at a low cost and (here’s the real key) without third-party supervision or government control. And I don’t think we know that. Bitcoin is scarce, but so are the watercolors I painted in high school. This does not make them a reserve of value.

In addition, Bitcoin-Heads should sign up for #fintechFT, our newsletter on the intersection of technology and finance. Click on here.

A good read

Caught my attention that Bloomberg story about how demand for homes in the U.S. is so strong that builders are moving away from fixed prices and doing blind auctions to get the highest possible bids:

“A collision of forces related to the pandemic [is] retain new inventory just when it is most needed. Buyers are rejecting new homes as remote work increases employment, while high wood costs and labor shortages slow construction.

This description suggests that there are no 2007-style toxic speculations in the mix. That makes me paranoid. Is there no speculation everywhere today? Why not housing? I don’t know if there is evidence that it exists, but I will look for it. If you have any, please email me.

[ad_2]

Source link