[ad_1]

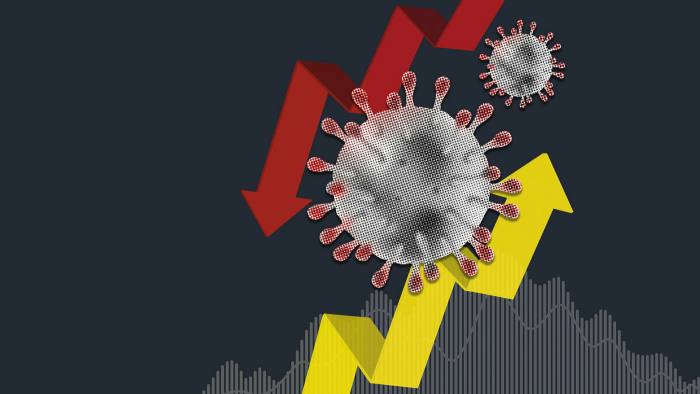

The fragmented U.S. health care system makes it difficult for the country’s efforts to sequence quickly Cases of covid-19 so it can track the Delta variant and possible future mutations, scientists and lab companies have warned.

Genomic sequencing is a vital weapon in the armories of public health officials as they fight to control variants such as rapid spread. Delta, as well as the effectiveness of vaccines against new strains.

However, healthcare in the United States, which is provided through a huge mosaic of public and private operators who often have difficulty sharing data, has caused the country’s genomic sequencing capabilities to lag behind others. countries with high vaccination rates.

“The UK took the lead in this space at first,” said Bronwyn MacInnis, director of genomic surveillance of pathogens at the Broad Institute of Massachusetts. “The United States did not do that, they did not give priority genomic sequencing until really the threat of the variants arose at the beginning of this year ”.

In the last 30 days, the United States has sequenced 2.8% of positive Covid cases and shared this information with GISAID, the world’s leading genomics database that helps keep track of new variants.

In comparison, the United Kingdom and Israel, countries with similarly high vaccination rates, have sequenced cases and shared data about three times that rate: 9.3% and 8.5%, respectively.

The United States also took more than two weeks to add its data to GISAID, compared to nine days in the United Kingdom and 12 days in Israel.

In the UK, health care is provided by the single-payer National Health Service, while Israelis are mandated to adhere to one of four official health insurance plans known as Kupat Holim.

“It’s still a logistical challenge,” said Will Lee, vice president of science at genomics firm Helix, which has a sequencing contract with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the leading public health agency. “With so many different places and means to get tested, it can be hard to get the sequences.”

“Because of the disparate nature of how things are handled in the U.S. from both a health care provider’s and public health perspective, gathering all the data is the challenge,” Lee added.

The CDC said it had partnered with clinical lab companies and university labs to expand the scale and speed of the country’s sequencing capabilities.

“As variants began to emerge. . . CDC established a multifaceted approach to genomic surveillance to monitor the evolution of Sars-Cov-2 and detect variants that are emerging in the United States, ”the agency said.

“With our current surveillance strategy, CDC is confident that new and emerging variants will be detected before they are highlighted,” he added.

But scientists say the genomic sequencing infrastructure in the United States remains slow and bureaucratic and the country runs the risk of detecting variants less quickly.

The CDC said it currently sequences about 10 percent of the positive cases identified in its own laboratories and partners, although this represents a fraction of the testing capacity, which is conducted primarily by private operators and hospitals.

Arthur Reingold, head of epidemiology at Berkeley Public Health in California, said the scattered nature of testing and sequencing was the “central reason” the United States had been slower in sequencing the virus. than the United Kingdom.

“If you have an NHS and accompanying labs … you can organize people and get them to do things in a consistent way much more easily than if you try to organize a lot of different providers and labs,” he said. “It’s a lot harder to put that together.”

MacInnis of the Broad Institute said: “We certainly had the ability to sequence and we didn’t miss positive tests for quite some time throughout the pandemicThe biggest barrier to “closing the gap” with other countries was the difficulty in getting positive evidence at sequencing sites, he added.

The different rules of the American states on data exchange also make it difficult to try to build a coherent picture of how and where new variants are emerging. Some states and health departments are unwilling to share detailed location data or detailed information, such as whether a positive person has been vaccinated.

“Every step of the way there are current regulations that try to protect individual privacy with privacy. . . But [they] it can also prevent the kind of rapid exchange of information we need, ”said Thomas Friedrich, a professor of pathobiological sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who has been sequencing Covid cases.

He added: “Each state and locality has its own mix of these regulations and different ways of interpreting federal regulations.”

Coronavirus business update

How does coronavirus affect markets, businesses, and our daily lives and jobs? Stay informed with our coronavirus newsletter. Sign up here

[ad_2]

Source link