[ad_1]

Environmental researchers have warned that illegal sand mining caused by a post-pandemic increase in infrastructure spending is causing the degradation of some of the world’s most vulnerable lakes and rivers.

Sand, mixed with cement to form concrete, is the most consumed material on Earth, apart from water. As the declining threat of the virus in countries like China causes renewed constructive activity, there are fears that criminal gangs that play a major role in the industry will be spurred to dredge even more sand from delicate ecosystems.

“From now on, we will see governments injecting a lot of funds into infrastructure to boost the economy, and that will lead to a lot of demand for sand and gravel,” said Pascal Peduzzi, head of the Global Resource Information Database. of the United Nations Program in Geneva.

Peduzzi explained that lakes and rivers were damaged by sand mining, which can change the course of waterways, reduce lake levels, erode banks and alter wildlife. “In some places, it has been such a heavy load in these environments that it has caused a total ecological disaster,” he said.

Kiran Pereira, author of Sand Stories: Amazing Truths About the Global Sand Crisis, said many major projects had already begun under the cover of the global health crisis.

“Covid has had the effect of increasing the amount [of sand] this is being extracted, “he said.” Many governments have used the pandemic as an excuse to carry out projects that would not have happened, such as land reclamation. “

The sand beneath lakes and rivers is better for making concrete than the sea or desert, too rounded to bind it with cement. Although sand appears abundant, it takes thousands of years to form through erosion.

Reserves are depleting rapidly, as sand is extracted faster than it can be replenished. Because extraction is poorly regulated worldwide and mining is often conducted informally, the activity is dominated by organized criminal gangs in many areas.

A paper published in March in the journal Extractive industries and society he highlighted how the sand mining industry was “affected by rampant illegality, a strong black market and intense violence”.

There is little global data on the problem, in part because sand is usually mined locally near where it is used.

“It’s the most exploited natural resource on the planet, and yet we know very little about where it comes from and who uses it,” said Dave Tickner, an advisor to WWF, the conservation group. “It’s an incredibly low issue given its importance to our daily lives.”

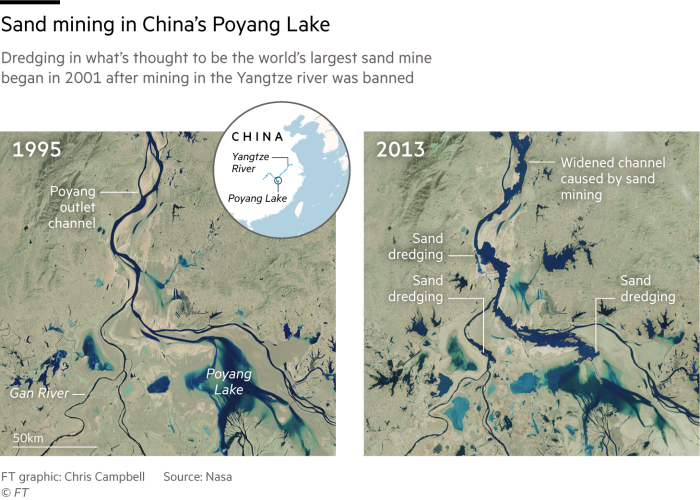

The problem is more serious in China, the world’s largest consumer of sand.

Beijing has relied on spending on state-dominated industries and infrastructure to drive a post-pandemic recovery. According to UNEP data, China accounts for 58% of global demand for sand and gravel.

High demand and the attraction of large profits have attracted criminals who resort to elaborate schemes to disguise their activities. They often operate at night with boats whose dredging apparatus is hidden by water.

A crackdown by Chinese authorities on illegal sand mining in the Yangtze River this year uncovered two dozen gangs involving more than 200 people and revenues in excess of $ 17 million ($ 2.6 million).

Interest in protecting the environment meant by repression comes as the country prepares to host a UN summit on biodiversity this year. “They [China] they have really intensified control and enforcement. They have really been reduced, ”said Pereira.

Still, environmentalists say what has been exposed is only a fraction of a vast illegal mining industry.

Elsewhere in China, intense sand extraction in freshwater lakes such as Poyang and Dongting have reduced water levels, increased the risk of drought and endangered local wildlife.

China’s insatiable demand for sand has also acquired a geopolitical advantage: aggressive sand mining around the Taiwanese island of Matsu has become a major point of friction between Beijing and Taipei.

China has also used large amounts of sand to build artificial islands that can house military bases and bolster Beijing’s claims in disputed waters.

Yu Bowen, a researcher at the China Aggregates Association, said coastal provinces like Fujian, in the Taiwan Strait, had thriving illegal markets.

“Companies are bidding to take over an area [of the sea] and then it’s theirs, “he said.” It could be a ship or 10 that were going to extract sand. That makes it hard to repress it. “

Mette Bendixen, an assistant professor of environment and geography at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, said the hot spot for sand demand would shift from Asia to Africa in the coming decades.

“The need for sand from Western countries is gone, the need for Asian countries is increasing and the need for sand from African countries will increase in the next ten years or so,” he said. “You may see the same horrible mining practices in Africa in a few years.”

Additional reports from Emma Zhou in Beijing

Carry on @ftclimate on Instagram

Climate capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore FT coverage here

[ad_2]

Source link