[ad_1]

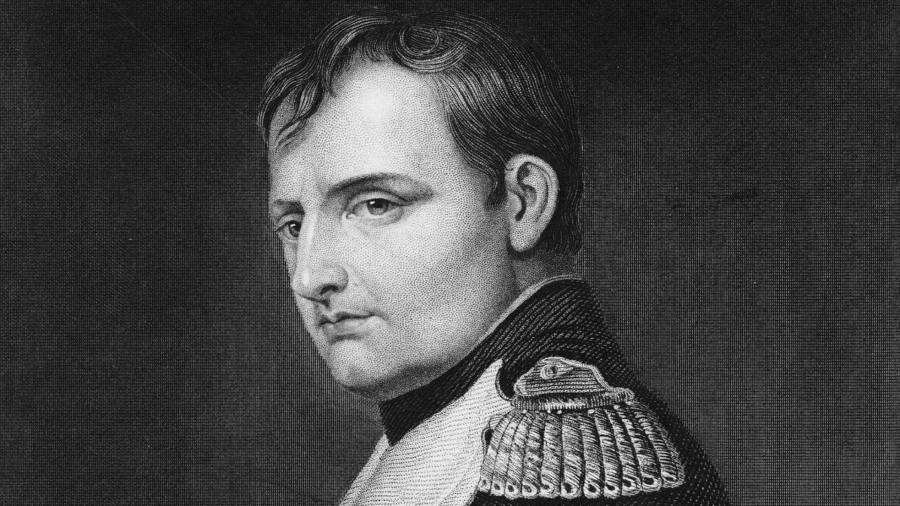

Fidel Castro he said once there are more people who know Napoleon Bonaparte for the brandy that bears his name than for Austerlitz, the most famous victory on the battlefield of the French emperor. On the 200th anniversary of his death, Napoleon’s legacy continues in more lasting ways than Castro’s credit gave him.

Two weeks ago, 20 French generals retired he called on the armed forces to save the nation so they called the dangers of radical Islam and the civil war. His call received enthusiastic support from Marine Le Pen, the far-right politician.

From a historical point of view, this incident served to recall the rich tradition of military interventions in French politics. It began with the coup d’etat of Napoleon in 1799. It continued with the coup d’etat of his nephew Napoleon III in 1851, Boulangism in the 1880s, The Vichy regime of Philippe Pétain of the 1940s and the army riots of 1958 and 1961.

A military coup is an extravagant idea in modern France. But among sections of the population, the impulse to find a greater savior of life, capable of transcending the divisions of France and revitalizing the national spirit, has persisted since the time of Napoleon.

Charles de Gaulle captured that momentum. For some of his supporters, so did the president Emmanuel Macron when he defeated France’s traditional political parties in 2017 and became the nation’s youngest head of state since Napoleon. Le Pen, who will challenge Macron for the presidency next year, he plays the same role for the far right.

Yet just as Napoleon was seldom a unifying figure of life, so too is his legacy dividing the present-day French. Opinion polls value it consistently as one of the two or three greatest historical figures of France. But Jacques Chirac, who hated him, he fled in 2005 Austerlitz bicentennial of commemorations as president. Alexis Corbière, a left-wing politician, he says France should not mark the bicentenary of his death because “it is not up to the republic to celebrate his grave.”

The arguments about Napoleon serve as a representative of the cultural wars waging France. Élisabeth Moreno, Minister of Equality and Gender Diversity in the Macron government, condemned he as “one of the greatest misogynists.”

Moreno probably had in mind Napoleon’s civil code of 1804, which specified that wives owed obedience to husbands. Or maybe he would have been thinking about it Germaine de Staël, the 19th century author who once asked Napoleon to describe the best kind of woman. He replied, “The one with the most children.”

In general, de Staël was not impressed with Napoleon. Comparing him to the austere Jacobin who led the terror of 1793-1794, she mocked him as “Robespierre on horseback.”

More recently, advocates of racial justice have seized power Napoleon’s decree of 1802, which aimed to reintroduce slavery in the French colonies after its partial abolition eight years earlier.

Napoleon’s admirers prefer to see in him the administrative reformer who created the national central bank, el high school school system and the prefects who oversee the departments. In this sense, he laid the foundations of the centralized and technocratic state that defines France to this day.

Critics emphasize the darker side of Napoleonic rule. This includes police repression, manipulated plebiscites and endless wars of conquest that worsened, leaving the national territory of France smaller in 1815 than it was before it took power.

In parts of continental Europe, Africa and Latin America, Napoleon has served as inspiration for national liberation movements. But in Russia and Spain he is remembered as an invader and for the British encapsulates the danger of a tyrant controlling Europe. Two hundred years later, the Napoleonic legend is alive and well.

[ad_2]

Source link