[ad_1]

One day when I was in high school, I wore a tutu on my head to class. I was following an impulse for drama. What I really wanted was widows’ weeds, especially those voluminous black nets that wealthy women in the 19th century would wear when a loved one died. I’d read Edward Gorey and fallen in love with the visual world of his books—a pastiche of the Victorian and Edwardian eras and the Jazz Age. In Gorey’s drawings, there was sometimes a woman sketched in long, elegant lines, surrounded by a fury of black veils, about to take part in some obscure, absurdist pantomime with an imaginary animal. I was enchanted.

But widows’ weeds are not easily purchased, and with the confident logic of adolescence, it seemed the black tulle tutu I had saved up to buy from Urban Outfitters would be just as good. I was convinced no one would be able to tell the difference. I remember the supreme satisfaction of carefully positioning it on my forehead so the rolls of fabric framed my face in a way that seemed infinitely intriguing. It felt so completely right that it was obvious. Surely everyone would look at this style and understand its magnificence.

My high school was a home for eccentrics; the joke was that the only rule on campus was you weren’t allowed to roller-skate in the halls. When I was there, some of my classmates got the cops called on them for fighting with swords from fencing class in front of the school, and the student lounge was stocked with a giant fishbowl full of condoms and cigarettes. It was a holding pen for teenagers too strange for the other prep schools in town and the half-forgotten offspring of diplomats and former noblemen. But even that conglomeration of misfits wasn’t accepting of my attempt at 19th-century mourning wear. The look was met not with ridicule or pity but with something even worse. When you are hoping your outfit will make an impact, the worst reaction is utter indifference. I wore that tutu on my head for an entire school day, and nobody said a single thing. When school was over, I took it off my head, more annoyed by the lack of response than the fact that I’d worn a skirt on my head in public.

The forays into mourning chic were a disaster. But I always remember that feeling of looking in the mirror and being entranced by the clothing I’d chosen. The chance to tell a story—big or small—through clothes simply felt too good to pass up. As anyone who loves fashion knows, clothing is a form of language, a way of communicating. It’s a dialogue with both oneself and the wider world. Some speak it more fluently, and more boldly, than others.

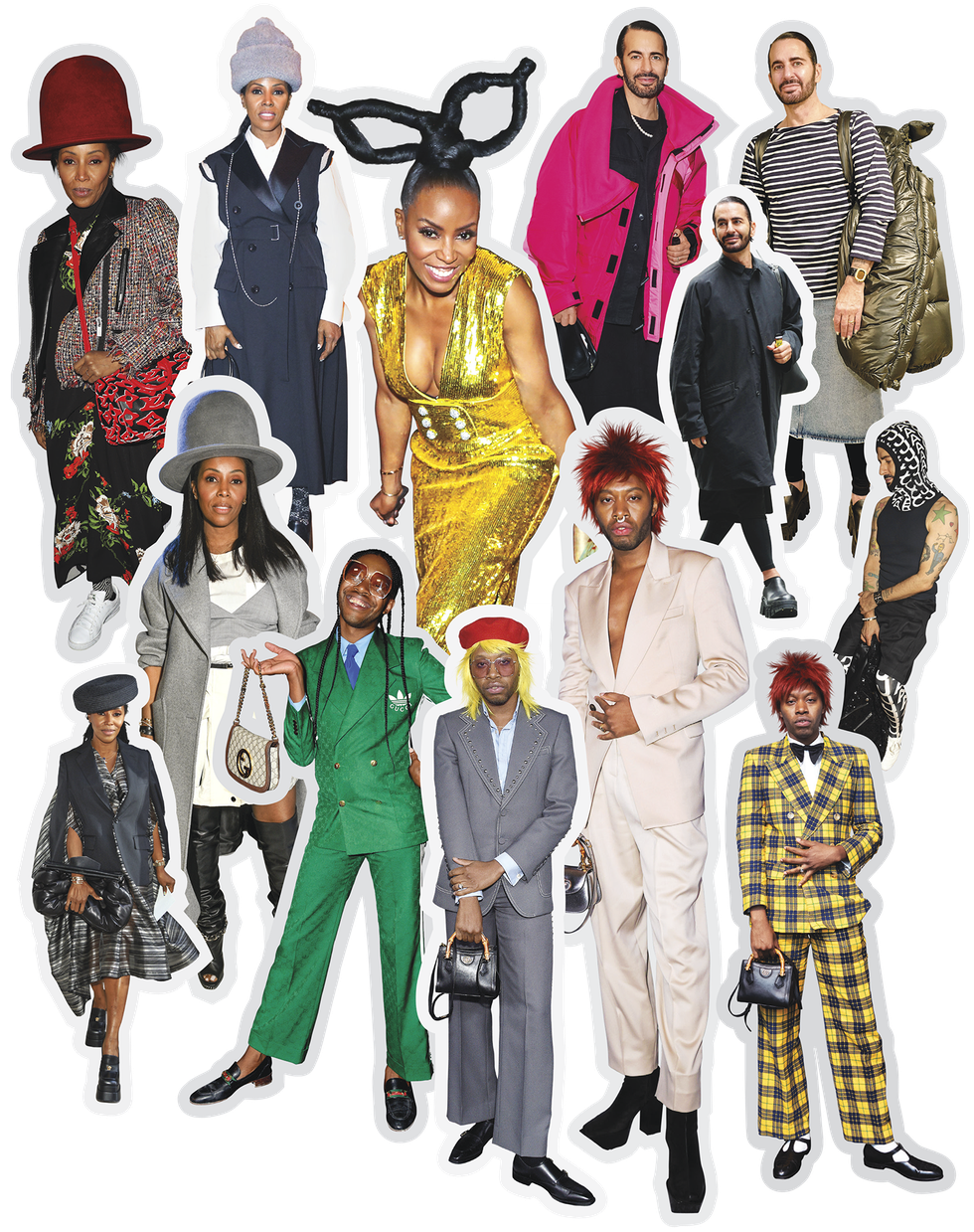

Here, I relate conversations I’ve had with people—artists, designers, thinkers, and makers—who speak the language of fashion with ease. For each of them, there’s an underlying sense of play in the act of getting dressed. The clothes themselves may convey any and every emotion, but the zeal with which these fascinating individuals play with clothing is always motivated by pleasure. The understanding of fashion as a form of social connection is overwhelming.

“A crucial element of dressing for joy is decentering what other people think about how you should be and centering what you feel about what you should be,” the author, poet, and comedian Alok tells me. “There’s a direct correlation between people who are doing really intentional healing work to accept themselves and people who have a more rambunctious sense of style, because it does take guts in a world that continually asks us, ‘What are you dressed up for?’ to respond, ‘Myself,’ and to mean it.”

Alok knows of what they speak. They are a multidisciplinary creative force whose books include Femme in Public and Beyond the Gender Binary, and their style is maybe best described as queer maximalism—brightly patterned dresses with bell sleeves and oxford button-downs in a deep, dusky rose. When I ask Alok what piece of clothing amuses them the most, they respond by showing me a pair of cat-shaped earrings by Deepa Gurnani. They are covered in beaded fringe to look like the shaggiest of animals—familiar enough in shape but just strange enough in detail to catch the eye. They are the kind of thing I’d have an internal debate about buying—weighing how much pleasure they bring me versus where I could actually wear them. But that inner debate misses the point Alok is making—the idea that taking pleasure in dressing is an exercise in shifting focus, in trusting oneself.

“What are you dressed up for?” was a question I heard constantly in my 20s. But by then, I had come around a bit to what Alok was describing; I had become even more entranced with dressing for myself. By the end of that decade, I was working for the first time in something like corporate America, at a company that desperately wished to appropriate all the signifiers of 2010s startup culture. It was, then, a very delicious power play to eschew the casual uniform of the office—leggings and hoodies and the studied disarray of not caring about one’s clothes because there were supposedly more important things to worry about—and show up instead in full skirts, sundresses, minis, and pencil skirts. It was an unabashed embrace of everything femme, and it was my main outlet of rebellion against a company I wasn’t sure I entirely trusted. The outfit I felt most powerful in, that brought the pleasure of ignoring convention, was a vintage rayon maxi dress in a deep purple and black, speckled with a pattern that could only have come from the ’70s, with a skirt that swept the ground. It was supremely satisfying to glide through the office, on the way to stand in front of yet another whiteboard with inscrutable industry jargon, dressed like an extra from Picnic at Hanging Rock. It was a reminder that I was not wholly a middle manager for content creators but something else, something more outside the particular ego-death of a whimsically named conference room with a blank projector screen.

That office uniform wasn’t just a power play; it was a good litmus test of who possible collaborators might be. I bonded with an art director over a Stüssy T-shirt—a man who would become one of my favorite colleagues. Dressing for yourself can serve as a kind of password, a signifier of your coconspirators, compatriots, like-minded friends—in short, who your people might be.

“I have a friend,” the L.A.-based vintage dealer Blythe Marks tells me. “She works as an analyst in D.C., which is funny given her extremely off-kilter style. She will wear a 1940s poncho with a 1960s clown uniform with clogs, like red leather clogs, and huge Iris Apfel glasses and a Peruvian pointed hat with flaps and tassels to the office.” Marks herself is known for wearing voluminous shapes, vivid hues, and graphic prints. Of her friend, she says, “We have a shared refusal to abide by the rules of so-called good taste, and refinement and corporate comportment have only enabled us to rebel further. I need someone like that in my corner.”

Fashion can let you know who is family—either your chosen family or family of origin. The jewelry designer, editor, and former model Michelle Elie says that “baptism clothes” are what she first thinks of when she thinks of joyful dressing. “All the ceremonial clothes bring automatic joy because you are about to celebrate something within yourself, for yourself, and with your community and friends and family,” she explains. But true pleasure, Elie says, is found in “everything gilded. Gold, gold. Layers and layers of gold. … I’m into chains now,” she tells me “I’m going like 10, 15 chains at a time. With my bathing suit this summer, I just decided I’m going to be chain, chain, chain, chain. It was the best because everybody else was just wearing a bikini. Very boring, very plain. And I came with 100 chains with my bathing suit. Fabulous. They were gagging. I had found all this jewelry for one euro at the flea market in Majorca, and I was like, ‘I’m living for it.’ ”

Like so many I spoke to, Elie finds contentment in the too-much, in the extravagance, in commitment to the idea that there is no need to ration pleasure. If you believe in its abundance, you can create enough to go around. Of the Maasai and Zulu beaded work that signifies the ultimate in fashion bliss, she says, “Incredible bracelets all the way up the arm. And then you have them on the neck … all these beaded necklaces. Divine happiness. That’s just beautiful.”

Dedicated practitioners of pleasure know that to choose beauty requires a discipline that brings deep rewards. “What I love about clothes,” the dancer and artist Connor Holloway says, “is you can put them on and feel a certain way one time, and then you can take them off and you never have to feel that way again. Or you can keep returning to it. That’s why I chose a career in performing,” they explain. Holloway is a corps de ballet dancer with the American Ballet Theatre and has been instrumental in increasing the company’s presence on social media. “I really love being able to try on something else for a while—keep the parts that you like and then leave behind the parts that don’t serve you.” There are no rules to how Holloway chooses to dress off the stage; they have worn a black lace dress reminiscent of some long-passed infanta or an outfit as simple as white pants and a tee paired with black Chuck Taylors. For Holloway, dressing is a cultivation of self-knowledge as well as a way of communicating with the world around them. They tell me about a particular sweater from Sky High Farm’s Workwear line that has little handmade bumblebees sewn on it. “Even the grumpiest baristas in the whole world crack a smile at it because there’s stuffed bees attached to it all down the arms. It’s better than any dating app I’ve ever been on because people will just approach me. They’re like, ‘Where did you get this sweater?’ And then we have a whole conversation.”

When you dress with confidence, you attract an audience and can forge connections you were not even looking for. “I have this Dries Van Noten shaggy kind of coat,” Amanda Murray, a freelance creative consultant, tells me. “It really makes me happy. Everywhere I go, people stop me. ‘Hi, where did you get that coat from?’ I went into Diesel over the weekend, and one of the employees said, ‘Oh, I really love that coat. Where did you get it from?’ I said, ‘Oh, I got it from Dries. It’s really old.’ And she said, ‘Who is Dies?’ And I said, ‘Consider this an education.’ ” Murray is describing one of the great delights of dressing for oneself: the chance to talk about one’s outfit with other people.

Dressing for joy is about channeling the desire for self-knowledge through the instinct to connect with other people, whether through conversation or the spectacle of putting on a show. Jalil Johnson, a street-style icon and the fashion office coordinator at Saks Fifth Avenue, says, “I get very dressed up to go to the theater. It’s kind of a lost art amongst the contemporary, because you’re seeing people going in jeans and flip-flops. And it’s like, this is special … we’re about to see art. And you’re looking at it as if it’s just a regular day. This is a special moment. Why not elevate it as much as you can?” Johnson favors dramatic black silhouettes when he dresses. With black, he says, “I think you can really play. And it really challenges you to be experimental.”

For June Ambrose, a longtime stylist who shaped the looks of Missy Elliott, P. Diddy, and Jay-Z and is currently the creative director for women’s basketball for Puma, fashion is a way to resist and defy expectations, particularly the ones that come with age. “I’m constantly tapping into my younger self to ask for permission to still be that way, to be curious, to be inquisitive, to be experimental,” she explains. “I think that as you get older, you start to become this person who’s like, ‘Well, this is my look.’ But there’s something about rediscovering yourself, reinventing yourself. It’s the joy of life. It’s different chapters, and you get to rewrite them.”

The act of dressing for joy may begin with the desire to please oneself first and foremost, but the outcome is always the bond formed with the wider world, the moment when a cat earring, a bumblebee sweater, or a vintage coat catches a stranger’s eye. The wearer notices the stranger noticing, and in that brief moment of looking, a kind of bond is formed, a reminder that we are social beings and that a life well lived is one that honors celebration.

[ad_2]

Source link