[ad_1]

India’s tea crop is at risk as Covid-19 infections spread to plantations that are already struggling with a torrid drought.

Ninety tea gardens in Assam, India’s leading tea-producing state, have reported cases and many declared containment areas, according to the local tea association, as authorities try to stop the spread of the virus in addition. of the state’s 800 plantations.

About 500 cases have been confirmed, but seedlings said more testing was needed to detect the true magnitude of the outbreak.

India is the world’s second largest producer of tea after China and competes with countries like Kenya and Sri Lanka in the export market.

Growers warn that if left unchecked, outbreaks could ruin the harvest season and raise prices.

“Last year, the tea gardens were miraculously saved,” said Prabhat Bezboruah, chairman of India’s Tea Board. “This time… The omens are ominous.”

The outbreaks in the tea plantations show the extent of India’s second wave that has left no corner of the country intact. The coronavirus has spread to remote areas after taking one devastating human toll in cities and disrupting industry and economic activity.

India on Saturday reported more than 326,000 new cases of Covid-19 and 3,800 deaths the day before. Experts believe the figures are a large number of infrastructures.

Assam and neighboring West Bengal, home to the famous Darjeeling tea-producing center, report each of their own climbs. Both states held recently local elections which public health experts said fueled the infection.

Labor groups blame what they call reduced working conditions on tea plantations for the increase in cases.

Homes “are densely populated. Workers work or move in large groups, so the possibility of a rapid increase in the number of infections among them is very alarming, “wrote Dhiraj Gowala, president of the Tea Tribe Student Association. of Assam, in a letter to the local government.

India’s tea industry is already weakened by everything from erratic weather patterns related to climate change to last year’s blockade, which led to the harvest to a stop for several weeks.

This lost production helped push India’s prices to record highs last year, giving Kenya and Sri Lanka an edge in the export market.

Ibi Idoniboye, an analyst at commodity data firm Mintec, said the latest disruption to Indian plantations could create another opening for producers like Sri Lanka to sell more to big consumers like Russia.

Producers are worried about facing another lost year. The coronavirus threat is exacerbated by a severe drought in Assam and northeast India, which has left withered tea leaves in its bushes.

“You put your hand on the ground and you just pick up dust. It’s usually lumpy and muddy for now, ”said Nazrana Ahmed, who runs a plantation near the town of Dibrugarh in Assam.

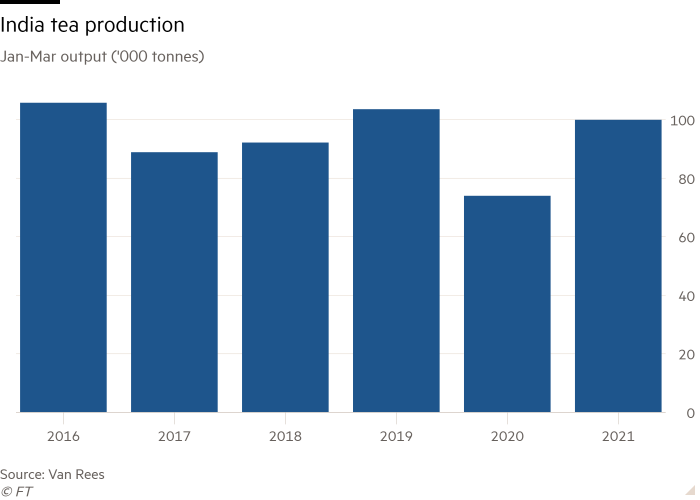

North India tea production of 47 million kg in March was higher than last year, according to tea trader Van Rees, but was still well below the 60 million kg harvested in March of 2019, the last “normal” year.

According to Mintec, the prices of tea auctions in Kolkata, the main export center, rose by more than 40% to Rs 287.5 per kg in April of the previous month.

Vivek Goenka, president of the Tea Association of India, said authorities were setting up vaccination camps to inoculate plantation workers, but were struggling to get shots in the middle of a severe country. shortage of punctures.

“We hope we can contain the situation,” he said. “I do not say that it will disappear overnight. . . It really depends on how fast and punctual we can control. ”

[ad_2]

Source link