[ad_1]

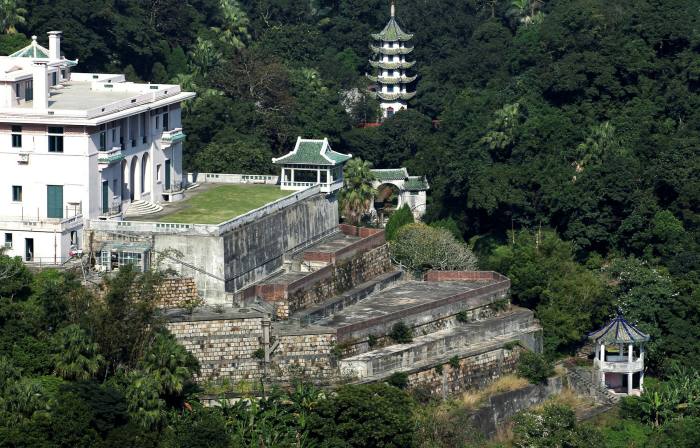

The building is still recognisably a house, but no one could call it a home. Through its narrow windows and across its deserted garden, there are few signs of life. Its driveway is covered in leaves, although it is not autumn, and the roof is slowly shedding orange tiles. Unusually for Hong Kong, it has a chimney.

From this high up the Victoria Peak, the view takes in almost the entire territory. In the distance, the skyscrapers of Kowloon shimmer eastward beneath a horizon of mountains. From the west, the sea winds around neighbouring islands into the harbour, where the boats are so small that they look like toys.

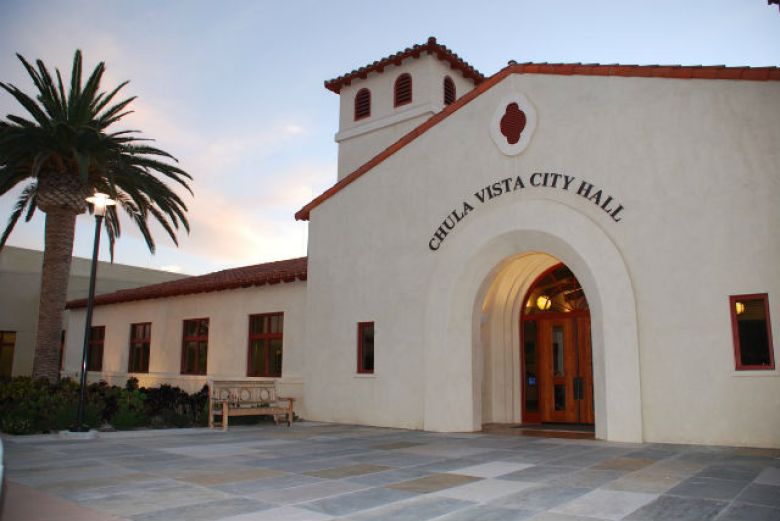

Dragon Lodge, as the house is known, occupies some of the most valuable real estate on earth. In 1997, the year that Britain handed Hong Kong over to China, it traded hands for HK$118m (about $15.3m at the time). But one day its last inhabitants moved out, and it has remained derelict ever since.

Confronted with this mystery, the internet has designated it one of the city’s most haunted houses. One rumour claims that construction workers refused to finish work on the site. Other blogs are more gruesome, stating that Japanese soldiers occupied it during the second world war and decapitated several nuns there. The current owners, faced with an onslaught of urban explorers, sealed off the premises with barbed wire.

But Lugard Road is a difficult place to ward off unwanted attention. As well as a prime property location — the Chinese conglomerate HNA sold a site there in 2019 for HK$550m — it is also one of Hong Kong’s most picturesque walking trails. As they pass, two hikers remark how “curious” it is that the house should be abandoned rather than let out.

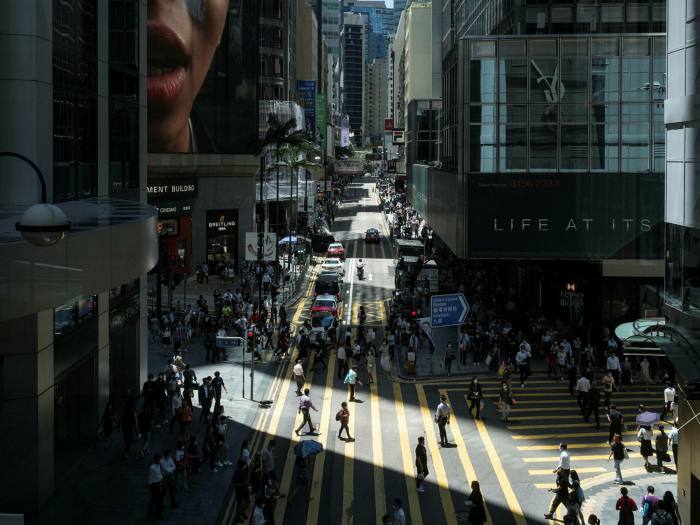

This curiosity arises because, in Hong Kong, you would expect every inch of space to be occupied. Despite the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and the waves of anti-government protests that started in 2019 — hundreds of thousands of British National Overseas (BNO) passport holders are expected to emigrate to the UK in the next few years — the real estate market is the most expensive in the world; and prices are increasing again.

Per square foot, the average cost of the territory’s luxury apartments rose 3.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2021 to HK$36,256, according to estate agency Savills.

There are, however, other factors at play. Jia, a jogger from mainland China, says that there might be a few “ghost stories” about the house. She lives on the Peak too and discussed it with her neighbour. He warned her of bad omens. “Whoever lived there,” he told her, “didn’t prosper.”

Superstition affects house prices

When one of Utpal Bhattacharya’s academic colleagues mentioned they were afraid to get out at certain subway stops in Hong Kong, he naturally assumed it was because of crime. He did not assume it was because of haunted houses. “I said, ‘What? You really take this seriously?’” he recalls.

A US professor of finance at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Bhattacharya, originally from India, set about researching the impact such perceptions might have on real estate prices.

The result of that study, which tracked unnatural deaths, showed a striking effect. Not only do prices for “haunted” units in apartment blocks drop by about 20 per cent, but those nearby can be affected too: units on the same floor drop by 10 per cent, and those in the same block by 7 per cent.

In Hong Kong, many “haunted” sites are well-known and have developed their own urban legends, such as Dragon Lodge and Nam Koo Terrace, which is also reputed to have been occupied by the Japanese during the war. But the city’s fascination with the subject is so strong that, when it comes to tragic incidents, legal precedents have been set.

A court case in 2001 found against an estate agent who had failed to inform a prospective buyer about the death of a four-year-old boy after he fell from the apartment balcony a year earlier. Banks in Hong Kong take such incidents into account when valuing properties for mortgage lending. Local estate agents keep lists of them too, for those either avoiding or seeking them out.

“It’s a phenomenal opportunity,” says Asif Ghafoor, chief executive of Spacious, a property listing site. His website’s haunted house filter gets more than 10,000 views a month. The legal risk is significant because of potential reputational damage to the property — in the past, people have tried to bring down prices by starting rumours — so every incident on there can be linked back to newspaper articles. “We’re not claiming we are a source of truth,” he says.

As with the coroners’ reports that Bhattacharya drew on, the list mainly consists of suicides and accidents. Agents tend to disclose such incidents. Joyce, 30, from Hong Kong, went to view an apartment several years ago in the city’s mid-levels, halfway up the Peak, that seemed cheaper than neighbouring options. The agent told her an apartment on the floor above her was haunted, as the result of a suspected suicide. “I just felt like, nah, I don’t want to live here,” she says.

For the undeterred buyer, reselling a “haunted” property could be difficult, Bhattacharya says, as the stigma isn’t erased by the change in ownership.

Foreigners are often seen as less susceptible to such superstitions, given their distance from traditional Chinese culture, but Bhattacharya also found anecdotal evidence of a 25 per cent hit to prices in the US, UK and Australia on homes that have been connected with murder and suicide in newspaper articles.

Ghafoor says he’s not aware of any formalised system of recording such incidents, like his, anywhere in the west, and suggests they are about “a form of residual trauma”. He remembers a colleague who died in his early twenties; he wouldn’t want to live in his flat, he says, because “I’d be thinking of him”.

What happened at Dragon Lodge?

Gerard Blitz, born in 1951 and now living in the Philippines, remembers many things from his childhood at Dragon Lodge. He remembers playing in the old Japanese war tunnels. He remembers Typhoon Wanda in 1962, which swept away the family’s bamboo greenhouse. He remembers a policeman showing him the revolver he fired at the Kowloon riots of 1967, when the British put down an uprising.

But he does not remember a single ghost story about the house, and neither do his siblings, Francis and Julia. Their mother was South African and their father was Dutch; he had been captured by the Japanese in Java during the war.

Later, he worked in the diamond trade and rented Dragon Lodge from someone Gerard remembers as a Chinese man called “Uncle Tom”. The 1948 phone book for Hong Kong lists a Tom ML as a resident there.

The house, the lot for which appears to date from 1921 and was last bought in 2004 by a company called East Team International Development (Nominee) for HK$76m, is not on the Spacious database and — while clearly abandoned, with the interior covered in graffiti — it is unclear why.

The closest thing to an “incident” that Blitz can recall involves a young lawyer by the name of Wimbush, who lived in the flat beneath the garden in the 1960s. In the 1980s, he was embroiled in the Carrian affair, a famous corporate scandal, and was found dead at the bottom of his swimming pool, at a different house, also on the Peak. It was ruled a suicide.

So why has it become thought of as haunted? One possibility is that ghost stories naturally attach themselves to empty homes. And in Hong Kong, there is a surprising number of abandoned buildings — so many that Facebook groups have been set up devoted to them.

While abandonments are often associated with money laundering from the Chinese mainland, tradition may play an important role too. One local expert in restoration, who asked to remain anonymous, says Chinese families often hang on to their parents’ flats after inheriting them, preferring to leave them empty out of ancestral respect rather than selling them. Once a unit is abandoned, the person went on, the stories follow naturally.

A representative for the company that owns Dragon Lodge says there is, to his knowledge, no evidence for the execution of nuns during the war, and that the company plans to preserve the house rather than lease, rebuild or sell it. They say it was built by a General Lung Wan, whose name contains the Chinese character for dragon.

Hong Kong heritage officials recently said they are reviewing a list of buildings for possible preservation, including Dragon Lodge. Recent restorations include the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, formerly a police station, which the British built in the heart of the city.

But the impulse to preserve can conflict with private ownership. The government tried and failed to save Ho Tung Gardens, which was demolished in 2013. Built in 1927 by Robert Hotung, who became the richest man in Hong Kong, it was the first building where a Chinese person had lived on the Peak after British colonial law restricted it to Europeans in 1904.

Restoration is part of the city’s understanding of its identity, the expert says, which was important because “we still don’t know who we are”. In a city obsessed with its future under the Chinese government, hauntings are a way of clinging to the past.

Remnants of a moribund empire

There is little concrete evidence of what — if anything — happened at Dragon Lodge during the war, and it is difficult to ascertain the prosperity of its previous owners, most of which are listed as companies. But Peter van der Voort, 72, a retired museum curator in Australia, grew up in the house next door to Dragon Lodge, and has a theory about how the ghost stories started.

Like his neighbour Gerard Blitz, van der Voort used to run amok in their corner of the Peak. He would “play Tarzan” in the jungle or go to the rifle range. But in the decade after the war, there was danger everywhere. Once, his friends found an unexploded grenade. Another time, he got trapped in a cave and couldn’t move forwards or backwards — he still dreams about it.

As well as his Dutch and American parents, who met in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in Shanghai, van der Voort was brought up by his amahs, Cantonese-speaking servants who lived in the house, “sort of like the governess”, he says. He remembers them as superstitious. Once he heard a shriek when he came home: someone had left a Clarks shoebox on the table.

House & Home Unlocked

FT subscribers can sign up for our weekly email newsletter containing guides to the global property market, distinctive architecture, interior design and gardens.

There was an abandoned house nearby — not Dragon Lodge, but another one — that he thinks had been shelled by the Japanese. It was his amah, he remembers, who told him the house was haunted, because that was the only way to stop him playing there. It worked. And he thinks the rumour caught on, but it was attributed to the wrong house. That was a long time ago, before the end of British colonial rule; he did not know he was growing up in “the throes of a moribund empire”.

There is another, much more recent explanation for its reputation. The representative for the owner says that, between 2008 and 2013, an investor based in the British Virgin Islands tried to buy the house. He suspects the investor spread the rumours, because they were “widely circulated” after the offer was refused, and another one was later made.

The representative added that the reason the house is not lived in is because there are so many hikers on the narrow road on Sundays and public holidays.

An explanation based on the lengths 21st-century investors might go to secure valuable property appeals to the rational mind, especially in the cold light of day. But after the sun has set on Dragon Lodge, and the joggers have all gone home, it is harder to overlook the residual presence of the past.

Behind the house, the black lampposts along Lugard Road look like they have been airlifted in from Victorian London. Amid the jungle and the roar of the cicadas, they suddenly seem lost. Their light is almost spectral as it illuminates the land, as though each night, they too must stake a claim to it.

Thomas Hale is the FT’s Shanghai correspondent

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

[ad_2]

Source link