[ad_1]

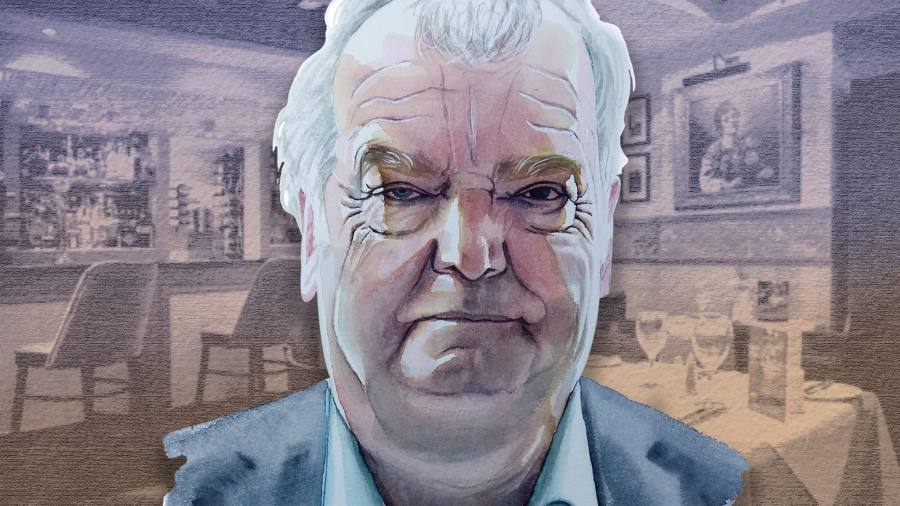

Sir Tom Devine is Scotland’s most distinguished historian since Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881), but unlike the latter — at least by reputation — he likes a joke. Shown to an alcove reserved for us in La Lanterna, his favourite restaurant in central Glasgow, he tells the waiters that he is on day release from Barlinnie, Scotland’s most distinguished jail. He keeps it up, enjoying the initial puzzlement.

Seated, he says he’s between two large meals, so won’t have much. “She who must be obeyed” — his wife, Catherine — had so decreed. The meal to come is with his large family of children and grandchildren; the gluttony past was yesterday’s magnificent dinner — of whisky-kippered salmon, beetroot, salsify and lemon, Dunlop (Ayrshire) cheese, bread and butter pudding, roast beets, leek porridge and rhubarb pie with cream — sent to him by the Sir Walter Scott society. Covid-19, which also must be obeyed, decreed they could not dine in a large group. He is due to give a speech at Edinburgh’s New Club later this year to mark the 250th anniversary of the great novelist’s birth.

We are meeting on the day after Scotland voted for a new parliament, and re-elected, with little change, a Nationalist leadership, as determined as before to pursue independence when — as first minister Nicola Sturgeon is now careful to add — “the time is right”. Devine might be called a conflicted nationalist: in the 2014 referendum, he was among the 45 per cent who voted Yes to ending the three-centuries-old union — although he actually wanted to vote for home rule, a choice short of leaving the UK.

In the second half of the 20th century Scottish politics was dominated by the Labour party, which scorned the struggling Nationalists as “tartan Tories”, a reference to the previously dominant but steadily diminishing Conservatives. But the Scottish National party grew and grew, until in 2007 it displaced Labour in the new Scottish parliament and has remained unchallenged since. At times it has ruled with an absolute majority, at times — as now, after this month’s election — with the aid of the pro-independence Greens. Sturgeon, leader since 2014, proved a decisive and reassuring guide through Covid, able to brush off a challenge to her rule from her predecessor, Alex Salmond, and claim that more than half the 5.5m Scots demand independence.

For Devine, the lack of the option of home rule is a missed opportunity for a Labour party which, even with a popular leader in Anas Sarwar, limped once more into third place in the election. “The Nationalists stole the leftwing clothes from Labour, and introduced identity politics,” he says. “One of the things I can’t understand about the current Labour party in Scotland is — why can’t they come up with a completely fresh agenda to offer the people, which means that the binary divide is cut off in the middle? They’ll never win against the Nats as faithful defenders of Scotland, nor against the Tories as faithful defenders of the Union. They’ve got to find a third way.”

I ask Devine what he means by this. “I mean devolution of everything apart from defence, etc, not the more radical option [devolving most macroeconomic elements] which would not have been conceded by the UK state. Nothing is certain in my mind until a referendum is called and its nature and process set out, except I have long believed the status quo is no longer acceptable. If it comes to the binary choice between status quo and independence, the latter will have my vote.”

It begs many questions: but he won’t be tied down to specifics presently. “I very much hope that the Scottish government accelerates serious work on the economic issues of independence,” he says. “The electorate needs time to assess the great short-term economic challenges of independence, how the government intends to tackle them and then plan on how the new sovereign state would exploit opportunities in the long term.”

He fears a grim time in the economy if independence is won — worried for his four children and nine grandchildren. (A fifth child, John, died aged 21. His is the dedication, in Scots Gaelic — Aig fois a nis, “at peace now” — in Devine’s masterwork, the more than 700-page The Scottish Nation from 1999.)

He chooses two starters: a minestrone and a chicken liver pâté, with toast and oatcakes. With a fine but not gluttonous dinner at friends’ the previous evening and a sandwich on a train before me, I order tuna and swordfish marinated in lemon and lime for antipasto, and capesante — grilled Scots scallops with a spicy risotto for main. Mine is delicious; Devine finds his to be better than Barlinnie’s. Neither of us drink wine: Scotland’s restaurants opened before England’s, on condition that diners remain dry.

Jovial, demotic, willing to pursue every line of inquiry, Devine owes his eminence to a discipline and austerity as pronounced as his lunch choices. Born in 1945, he grew up in a Scots-Irish family. His grandparents — “they were peasants” — had come over from what was then British Ireland in 1890 to find work in the steel and coal industries at the heart of a shipbuilding and heavy engineering complex that the US was only beginning to rival.

Menu

La Lanterna

35 Hope St, Glasgow G2 6AE

Minestrone £5.50

Chicken liver pâté £6.95

Tuna and swordfish antipasto £8.95

Capesante and spicy risotto £22.95

Double espresso X2 £5.50

San Pellegrino X4 £11.80

Total £58.70

Devine’s father, last of a large family, benefited from enough accumulated savings to be sent to university, and taught at a school for the rest of his life. Open dislike of the Catholic Irish then was, he says, “a daily event, unavoidable”. It gives the Catholic Devine’s eminence as the national historian an extra edge: in Scotland, the religious divide, while much diminished, still matters.

As a young scholar rising in rank, he began his career at Strathclyde university, where he had studied. Outside the circle of the four ancient Scots universities founded in the 15th and 16th centuries, it received its charter only in 1964. Devine turned its history department into the top-rated in Scotland. After almost three decades there, he moved to be founding director of the Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies at Aberdeen, moved again to Edinburgh for the prestigious Fraser Chair of Scottish History, was founding director of the Scottish Centre for Diaspora Studies, and retired to his emeritus years in 2015.

Devine has been outspoken in his criticisms of “cancel culture” in Scottish universities, from which he thought they were immune. It has kept him in the public eye, not always a kindly one. He argued against the campaign to remove the statue, in Edinburgh’s St Andrew Square, of the late 18th-century politician Henry Dundas. Dundas held a series of high offices, including the effective management of Scotland. The campaign accused Dundas of delaying a bill, sponsored by the abolitionist William Wilberforce, to end the slave trade in the British empire.

Having read up on the case, Devine accused the campaign of bad history, arguing there were larger political and economic forces that prompted the bill’s delay — and would, had it been tabled in the late 1790s, have doomed it. It set him against another emeritus knight, Sir Geoffrey Palmer, a Jamaican-born scientist, who has led the campaign against Dundas — a campaign that did not seek to drag Dundas off his 150ft pillar but convinced the city council to affix a plaque to its base.

The inscription says Dundas was “instrumental in delaying the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade . . . as a result of this delay [until 1807], more than half a million enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic . . . he curbed democratic dissent in Scotland, and both defended and expanded the British empire, imposing colonial rule on indigenous peoples . . . In 2020 this plaque was dedicated to the memory of the more than half a million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas’s actions.”

Devine is outraged by this. “I have deep respect for Geoff Palmer as a social activist and a man but his history is fundamentally erroneous. What caused the postponement of the end of the slave trade was that no British government, in the context of war with France, would have damaged the trade with the West Indies, which was the jewel in the economic crown. The bill would have failed if put then. I think the individual in history can be important — but he or she has to be put in context.”

Devine has also spoken out against the removal of philosopher David Hume’s name from the 1960s tower that houses part of the arts faculty in Edinburgh’s George Square: he believes the university’s vice-chancellor, Peter Mathieson, has done too little to oppose that and other such episodes.

“It’s unambiguous . . . what Hume said on slavery,” says Devine. (In Hume’s essay, “Of National Characters”, one of many from the 1740s, the philosopher wrote that: “There never was a civilised nation of any other complexion than white.”) “But to use the old cliché,” Devine says, “he was ‘a man of his time’ and that was when Scotland was deeply embedded in the slave system, possibly to an even deeper extent then [than in the 1790s]. History must excavate and respect facts. Don’t judge the past by the values of the present. It’s the first law!”

Recovering Scotland’s Slavery Past, a book Devine edited and for which he wrote three essays, reveals the large role Scots played in managing the trade and running the West Indies plantations. It flays the hypocrisy with which some Church of Scotland ministers and the Glasgow merchants — who had benefited greatly from the cotton and tobacco produced by slaves — had, after the abolition of slavery in the British empire in 1833, preferred to “ignore or marginalise the history of slavery itself and focus instead on celebration of the moral victory of emancipation”. Devine agrees that Scots like to think of themselves as a more moral people — “and more intelligent”, he adds — than the English.

He praises the work of the independent historian Gordon Barclay, who has exposed the nationalist myth that claimed falsely that troops were sent by then home secretary Winston Churchill to quell the 1919 “Red Clydeside” strikes and bring in tanks to face strikers in George Square. (I later spoke to Barclay, who said the claim leaked into the school exams from 2013 and stayed there until corrected five years later.)

“He [Barclay] and others transformed that situation,” says Devine. “The textbooks have to be rewritten for kids. It is very difficult for the teachers. Scottish history has gone through a revolution in the last few decades: the teachers haven’t the time to read the learned journals and keep up.

“Scottish history had been neglected: the year I went to university, in 1964, the new professor of history at Aberdeen, an Englishman, stated in his inaugural lecture that ‘the history of Scotland is less studied than the history of Yorkshire’. English historians, realising what was in the archives which had never been read, came up here to do the work . . . They played a major role in the historiographical revolution that was under way.”

Not the usual speech of a Scots nationalist. Indeed, as the talk went on, I thought that Devine was less a conflicted, more a fatalistic nationalist. For independence, he still has many doubts about the governance of the SNP, which is now starting its fourth term in power in the Scottish assembly. He cites instances some pro-independence commentators — the journalists Kevin McKenna and Iain McWhirter, the academic James Mitchell — who, though pro-independence, have been strongly critical of a party struggling with school results lagging behind others in the UK, a health service plagued with problems, and local authorities stripped of cash and powers. A kind of consensus seems to be forming in the political classes: that independence must come, but that its vehicle, the SNP, has not risen well to the task of governing.

His fatalism comes from this: that when England grasped, after the Union, that it must respect Scotland’s past statehood as well as present nationhood, it exercised “restraint” in governance. “It’s almost a unique exemplar . . . of a big brother treating a younger brother with a great degree of sensitivity,” Devine says. “Now, there’s a movement away from sensitivity and law, respect, to a situation of constraint — an aspect of Brexit, an aspect of the Johnson ‘no’.” He argues that the loosening of the Union is less to do with the decreased potency of Protestantism, empire and monarchy — the historian Linda Colley’s view in her influential Britons (1992) — and more a straightforward question of the fundamental way in which its management has changed since 2014.

“I’ve always thought that England would destroy the Union. The history of European multinational states shows the rot tends to start from within, and then spreads out to the peripheral nations.” He had hoped the rot would stop if Labour returned to power in England. “But look at today,” he says, referring to the Hartlepool by-election in which the Conservatives had taken the traditionally Labour seat.

“This cements the view here that these people in Westminster are in government for the foreseeable future. There is a sense in Scotia that the two nations are going in opposite ideological directions. And these directions will accelerate in the future — ergo Hartlepool. One of the reasons my family, like most Irish Catholic families, didn’t vote Nationalist in the period [of Nationalist advance] was the feeling that ‘we can’t leave our brothers in northern England to rightwing Toryism’. It was a conscious feeling in Labour — and it meant not going over to nationalism. And now . . . ”

And now, he says, “the danger for the UK is much more profound than it was in 2014”. Independence, on this view, is strengthened when the brothers in the north of England are no longer to be saved from the Tories — because they are the Tories. And Scotland thus must, faute de mieux, go its own way. With that, Devine goes off in his own way — not to Barlinnie, but home, for another family feast, constrained by lack of English restraint to follow the hard path to independence.

John Lloyd is an FT contributing editor

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

FT series — Scotland’s future

From the battle for independence to life after oil, we examine Scotland at the crossroads. Plus reflections on the Scots language, the best way to drink Scotch and more, here

[ad_2]

Source link