[ad_1]

By Kevin Schofield

This weekend’s reading is a fascinating article looking at the current Supreme Court and comparing it to its predecessors over the past century.Regarding one question: How business-friendly is the Roberts Court? (Different Supreme Court eras are generally defined by who was the chief justice at the time, perhaps giving these justices much credit for their influence over their colleagues.) The article was written by two law professors: Lee Epstein at the Univ. of Southern California and Mitu Gulati at the University of Virginia School of Law.

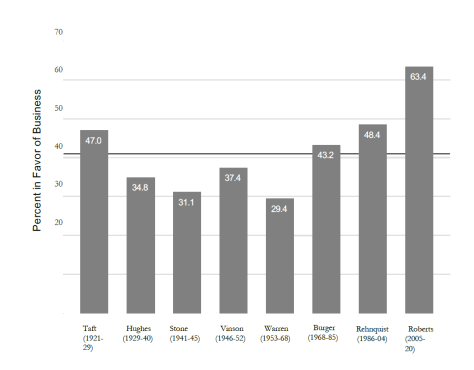

Measuring the extent of the court’s “business-friendly” bias is difficult. A simple measure is to see how often a business interest (either a company itself or an association such as a chamber of commerce) prevails in a court case. But with respect to the Supreme Court hearing the case, ideally, we have to look at whether it is choosing to hear business-related cases at all and how it is choosing the cases it deals with. And it may be that lower courts are more business-friendly, so a business-friendly Supreme Court may not find it necessary to rehear a case when it agrees with a lower court ruling. We also need to recognize that “business-friendly” is relative: for example, over the past 100 years, businesses have won 41 percent of their Supreme Court cases, slightly lower than the 42 percent win rate for criminal defendants and far less than the 54 percent win rate. Victory rates for plaintiffs in civil rights cases. But there’s a lot of variability in that 41% rate: The Taft Court (1922–1929), considered by historians to be the most business-friendly because it overlapped with former business lawyers, had a 47% win rate for businesses, while the Warren Court (1953– 1968) businesses won only 29%.

By this measure, however, today’s Roberts Court still stands alone, with a 63% success rate for business. In the 17 years Roberts has served as chief justice, his success rate has steadily increased: after a low of 53% in 2005 and 44% in 2008 and 2009, it has now risen to 70% in 2019. A whopping 83% by 2020

After laying out the basic statistics, the authors dive into trying to understand the factors that might make the court more business-friendly. What’s clear is the judges themselves, and the authors’ analysis shows that judges appointed by Republicans are more likely to vote pro-business than those appointed by Democrats. In fact, the six Republican-appointed justices currently sitting on the Roberts court are the most pro-business of any justice in the last century. However, the authors also note that all three Democrat-appointed justices — Kagan, Sotomayor, and the recently retired Breyer — have voting records that also make them “business-friendly” by historical standards: Sotomayor’s 48% rate, the lowest of the three, is still higher than the combined totals of the Taft Court and Taft himself.

Beyond the justices themselves, the authors look at a few other possible factors that make Supreme Court decisions business-friendly. First, the federal government itself weighed in as a direct party or “friend of the court.” Statistics show that the Attorney General of the Supreme Court is the only attorney responsible for representing the federal government in front of the Supreme Court. 20% of the time.

The authors also pointed out that there is an increase in the number of experienced lawyers in front of the court. This is representing business interests in court cases. Today, 77% of lawyers representing businesses have Supreme Court experience, compared to 25% in the Burger Court (1969-1985). According to the authors’ analysis, both Democratic and Republican-appointed justices are more likely to support business when represented by an attorney with Supreme Court experience.

Finally, the authors looked at whether public sentiment plays a role, as another analysis shows that Supreme Court decisions over the years have tended to be tracked by public sentiment. First, it should be pointed out that the Roberts court seems more disconnected from public sentiment than its recent ruling should be overturned. Roe v. Wade stands out as a key example. But as public sentiment toward business has gradually declined over the past 30 years, the court’s pro-business tilt has followed an upward trend since the late 1960s. The Supreme Court is bucking the trend on business, and has been doing so for a long time since the Roberts Court.

As the authors point out in their essay’s conclusion, while it is clear that the Roberts Court is more business-friendly, there is no single reason why. And like many good pieces of research, it raises a series of questions that need further study as we try to understand this important trend in how our courts treat wealthy and powerful corporations.

A Century of Business in the Supreme Court, 1920–2020

Kevin Schofield Freelance writer and publisher Seattle Paper Trail. Previously worked for Microsoft, published Awareness of the Seattle City CouncilHe co-hosted “Seattle News, Views and Brews.” Podcast, and raised two daughters as a single father. He serves on the board of directors of the Woodland Park Zoo, where he also volunteers.

📸 Image courtesy of Shutterstock.com/Brandon Bourdages.

Before you move on to the next story … Please consider that the article you just read was made possible by the generous financial support of donors and sponsors. The Emerald is a BIPOC-led nonprofit news outlet with the mission of offering a wider lens of our region’s most diverse, least affluent, and woefully under-reported communities. Please consider making a one-time gift or, better yet, joining our Rainmaker Family by becoming a monthly donor. Your support will help provide fair pay for our journalists and enable them to continue writing the important stories that offer relevant news, information, and analysis. Support the Emerald!

[ad_2]

Source link