[ad_1]

As an executive at Pepsi, JR Harris conducted market research in 56 countries and traveled extensively for work. And after he quit in 1975 to found his own market research company, his clients have remained mainly international.

As with most road warriors, commercial travel was of little interest. On the other hand, he liked to walk alone, in remote areas. He rarely travels as a mere leisure tourist, but when we spoke earlier this month, he told me about his past.

I went to South Africa in 1982 as a tourist.

This in itself would have been somewhat interesting; Apartheid was then the law of the land. What makes it particularly surprising is that Harris is black.

“Everybody had an opinion about it.” “But it occurred to me that if I really wanted to know what it was like, I had to go there.”

He applied for a tourist visa at the consulate in New York. The consular officers seemed unsure about a black man applying for a tourist visa and what to do. They told him to have a seat.

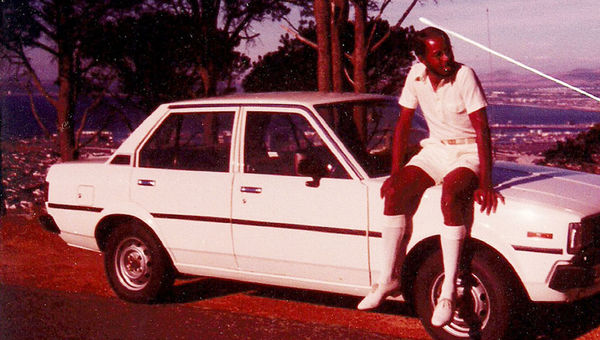

JR Harris, with his rental car, in Cape Town, 2011. Around 1982. Although he was repeatedly stopped by the police, his status as a “gentleman white man” made the stops difficult. Photo credit: Courtesy of Thelma Ngkobo

Others who entered after him were called before him. “I finally went up and said, ‘What’s the story? I was here all afternoon.’

“We’ve never met a black person who wants to go to South Africa as a tourist,” the woman at the desk told him. “We had to call Johannesburg to see if he was okay, but we found out the office is closed, come back tomorrow.”

He did. And the next day he got his visa. “But they still looked at me like a crazy person,” he said.

They also explained the rules: He had an American passport and was not subject to the restrictions on black South Africans. “They gave him a document that officially made me an honorary white man. I’ve been called many things in my life, but never,” he said.

There was one limitation worth noting, they continued. Restaurants had a star rating system, and any five-star restaurant, the highest level, would keep it. But if an owner voluntarily downgrades to four stars, they reserve the right to refuse service.

Armed with his visa and documents, he bought a ticket on South African Airlines – first class. The sitter was already sitting down when he boarded. “‘Oh no, no, no, no, no,’ the man said when he saw me,” Harris said. “I’m not going to sit next to him, I need another seat.”

But nothing was found in the first class, the flight attendant explained. The only option is to sit as a coach. “Well, I’m not going to sit here,” said the man, and he took the carrier out of the box and went back to the coach – a show of support from the other whites in the first class.

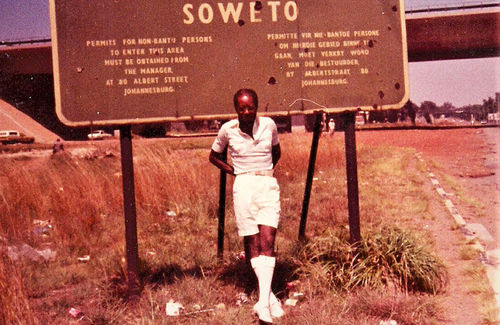

Harris also visited the segregated black town of Soweto, Johannesburg. Photo credit: Courtesy of Thelma Ngkobo

Undeterred, Harris toured the country for two weeks, from Soweto to Sun City to Wine Country. On Table Mountain in Cape Town, Nelson Mandela looked down on Robben Island, where he was imprisoned. They even visited the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria to learn more about the Boer culture of the founders of apartheid.

He drove to Cape Agulhas in a rented car to become the southernmost person in Africa, to book his first solo trip, after college he drove to the northern tip of Alaska so that no cars would come between them. and the North Pole.

There were occasions when he was told that in the absence of five-star restaurants in small towns in South Africa, he could not be served but would buy food in his car. “They were always polite, they made a point to say they weren’t the owners,” Harris said.

His car was stopped by police several times, but his “honorary white” status made the stops short and unsuccessful, he said.

None of his experiences came close to the disappointment he felt when, still in high school, he made his first trip to the segregated American South to visit friends in South Carolina. On the train back, the conductor, who was black, told him to stand instead of sitting. It was said, “A white man is asleep in your chair, and I will not wake him.”

Harris asks how long the interloper will be on the train. “On his way to Washington, DC” — less than eight hours — was the reply.

Generally speaking, Harris said he was welcomed wherever he went.

“I was born restless, I was born curious,” he said. “The only time I really don’t feel welcome is when I’m hiking in grizzly country.”

[ad_2]

Source link