[ad_1]

In the year In the 1960s, they often tried to imagine the clothes of the future – designer Hardy Amis’s wardrobe for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, inexplicably from 1968, see pieces from the period. Issei Miyake was working on the first “buildable garments” – knitted pieces that could be put together on demand. Their seemingly simple shapes are soft, and the novel synthetic fibers are tender. They haven’t met one day and still look like they might be in the future.

Miyake, who has died at the age of 84, always said that he was not interested in fashion, only designing for a living. He thinks about the relationship between people and the fabric that covers and envelops their bodies, about fabric fibers and techniques. Its simplicity harkens back to ancient Japanese dressmaking principles, where rectangles were folded and folded into a garment, and to the future, the computer-controlled 2000-line A-PoC (A Piece of Cloth) that produced tubular fabric so that wearers could cut seamless garments.

Miyake looked at craftsmanship and cultivated chemistry and technology with equal curiosity – his polyester bao bao bags are sturdy on a mesh backing, yet flexible like samurai armor. It was an early adopter of digital design for mass production with computerized machinery. The more precise and perfect a repeatable process becomes, the closer it becomes to craftsmanship.

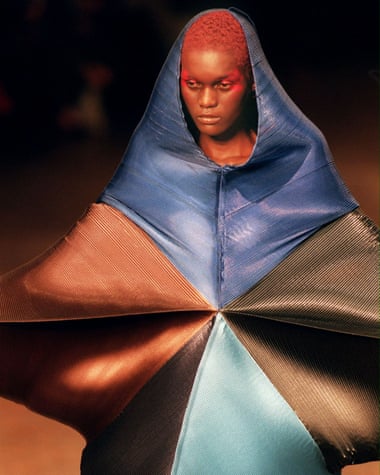

His most successful concept, Pleats, owes its bark-like aesthetic to vintage Greek linen dresses, 1910s draped gowns, and the relative affordability of pleats, a bark-like aesthetic, and the affordability and texture of polyester baked to relatively new attractive machines. with memory.

Miak experimented with hundreds of beautiful costumes for William Forsyth in 1991 at the Frankfurt Ballet’s Loss of Small Details, and at the line’s 1993 launch, dancer models unleashed every bit of kinetic energy rocking those costumes. Irving Penn happily photographed them. In turn, Miyake dresses became a gala favorite of ballerinas and classical musicians, guaranteed never to tire when the conductor embraced them. Architects also admired him. His most esteemed repeat customer is Apple’s Steve Jobs, who described the black turtlenecks he ordered down to the millimeter.

Miyake researched materials and was excited: “Clothing materials are limitless. Anything can make clothes.” That included wood cellulose for student designs in 1963 for the Toyo Rayon Company. Pineapple fiber and rubber; Paper, rattan and bamboo – the traditional craftsman wore these in the Miyake bodice that put him on the cover of Artforum magazine in 1982, and it was the first garment to be honored.

Above all, he had an extraordinary respect for materials derived from fossil fuels, seeing plastic, nylon and all polishes not as cheap disposable substitutes for natural substances, but as having their own unique properties – the polyfibres produced by adventurous manufacturers were machine washable, unbreakable. , elastic and kind to the skin. Hi-tech manufacturing processes reduce waste as well as fabric waste; The clothes were visually timeless and physically made to last. Miyake never thought of hydrocarbons as an infinite resource to burn. Their complex chemistry and potential uses proved valuable – they made long-gone sun-kissed clothes and water-based perfumes, starting with L’Eau d’Issey in 1992. Durable, wearable fabric up.

The lab was Miyake’s living aging project after handing over design responsibility for eight major lines, including Décor, and international sales and stores, to his personally handpicked successors (the company remains privately held) in the 2000s. Since the opening of the first design studio in 1970, it has been a vital research and development facility where fellow employees have shared experience and a base of communication with artisans, machinists, suppliers and digital testers. with young recruits. It has long been a popular term and practice. monozukurithe creation of things, which meant more than manufacturing.

Miyake never expected to reach old age. Born in Hiroshima, the son of a military officer and a teacher, he moved to a small nearby town during World War II. In the year He was in elementary school when he saw the flash of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 at 8:15 p.m. Seven-year-old Miyake walked alone to the family home, 2.3 km from the epicenter, to search for the piled-up dead and his mother.

She survived, badly burned, and died three years later, after nursing him with osteomyelitis, a radiation sickness that left him paralyzed. Miyak grew up painting the poor, slow-built city – too weak to buy brushes, he worked with his fingers – and the Peace Bridge there, Isamu Noguchi’s deep concrete ballasted sign of the future, he crossed on his way there. Painting the rooms. Former students at Hiroshima’s Kokutaiji High School, some of whom died young from radiation sickness, told Miyake about his hero (and later friend) Noguchi. Miyake also thought he would die young, so he ventured into becoming a designer.

Images in his sister’s magazines sparked an interest in clothing, but it wasn’t a possible subject for men’s studies in 1950s Japan, and he took graphic design at Tama Art University in Tokyo to accommodate his father. As a student, he wrote to the office of the World Design Conference held in Japan in 1960 to find out why clothes were not part of the program.

With no place to study couture, after Japan allowed him to travel abroad on a shoestring budget, he went to Paris in 1965 to take a couture course at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haut and interned for Guy Laroche and Hubert de Givenchy. But the important lesson in Paris was the student protest in 1968, rebelling against the haute-bourgeoisie, the usual couture customers. Miyake sided with his students, wanting to make clothes that were wilder and more practical, for ordinary people, not limited by age, size, gender or style.

Miyake moved to New York in 1969 as Geoffrey Beene’s assistant to learn about mass production. But in 1970, another radiation-related illness sent him back to Tokyo for treatment, and friends loaned him the money to start the Miyake Design Studio. At his dramatic debut in Tokyo, a model stripped off several layers until he was naked, a scandal that shocked sponsors and made his core clear.

In the year He began to appear in Paris in 1973, unlike other Japanese designers who arrived there. His formal collections of tailored and high-end clothing were impressive, but the real joy came in the 1990s with a shift in focus to volume production of ready-to-wear lines. They introduced him to his idealistic, non-fashionable clientele.

As well as the Realty Lab, Miyake has “retired” at Japan’s first design museum 21_21 Design View in Tokyo with architect Tadao Ando, a corrugated metal roof based on fabric. Miyake’s own creations have been exhibited and collected in museums including London, New York and Paris. Japan gave him a cultural order in 2010.

Miyake kept his childhood grief a secret until 2009 and was secretive about his personal life: his closest associates were his work colleagues, most notably studio president Midori Kitamura, a former model.

[ad_2]

Source link