[ad_1]

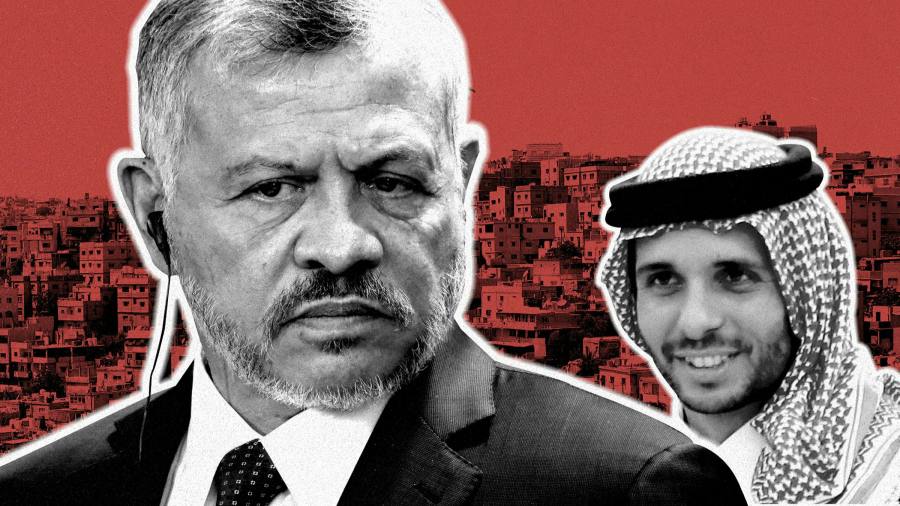

About eight years ago, Prince Hamzah bin Hussein brought an idea to his half-brother, the King of Jordan. For years, the many tentacled Jordanian security and intelligence services had been at odds with each other, caught up in a decades-long battle for control of the most powerful institutions in the Arab kingdom. Two previous chiefs of the Dairat al-Mukhabarat, or General Intelligence Directorate, had been jailed for corruption.

“It was a dark period,” says a western diplomat. “Open corruption, inter-services turf battles, briefing and counter-briefing on each other, completely eroding their effectiveness.”

Unseated as crown prince in 2004, Prince Hamzah had been asked by King Abdullah to come up with a plan to make himself useful to the Hashemite dynasty. That day, says a person briefed on the exchange, the brash prince made a bold suggestion: unite all the military intelligence services into one wing and place him in charge. King Abdullah declined. Placing Prince Hamzah — who the king had passed over in favour of his own son for succession to the throne — in such a powerful position was “unthinkable”, says the person.

Since that rejection, Prince Hamzah, 41, has pursued a different track — making deep inroads into the far-flung and disaffected tribes that a century ago helped create what grew into the modern state of Jordan. Now a minority in their own country, some tribal leaders complain of being left behind, with their young people unemployed. In the prince, they found a sympathetic ear.

“He would ask us how we were,” says Dahham Methqal al-Fawwaz, a 38-year-old tribal leader from the Serdi clan in the north of the country, close to the border with Syria. “And he would listen, when I would tell him of the sadness in people’s faces, grim with the hardships they have to bear.”

That tactic — courting the tribes — eventually brought the ambitious prince and the rest of the ruling family into open conflict two weeks ago, with Prince Hamzah placed under house arrest, stripped of all means of electronic communications and eventually subdued into signing a pledge of allegiance to the 59-year-old King Abdullah.

The extraordinary public feud has pulled back the veil on long simmering tension among one of the Arab world’s most respected royal dynasties. Jordan’s western-educated ruling elite, compliant intelligence agencies and reliability have made the kingdom a staunch and dependable ally for its closest friend, the US, which has rewarded it with billions in aid.

At least 18 more people, described by the government as co-conspirators in a seditious plot, have been arrested and a sweeping investigation is being carried out, spearheaded by the Mukhabarat.

Intercepted WhatsApp and other messages described to the FT by Jordanian officials paint a pattern that goes beyond the cultivation of a rival power base — they suggest active collusion with Bassem Awadallah, a Jordanian adviser to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who reportedly dislikes the Jordanian king. The messages are said to include a discussion of various dates when the prince could call on his supporters to join street protests.

The officials say Prince Hamzah asked members of this message group, including Awadallah, if he should throw his support behind a series of independently planned protests on March 24, called by a youth movement that has previously organised Arab spring-inspired demonstrations for political reform.

Is it the right time, Prince Hamzah is said to have asked Awadallah, in a text message described to the FT. “I don’t want to move too quickly,” he said, according to a Jordanian official.

Economic hardship

The prince’s alleged pursuit of the tribes’ backing — two Jordanian officials describe it as the first stage of seeking their formal allegiance — struck at the very core of the legitimacy of King Abdullah’s reign. The tribal leaders who spoke to the Financial Times describe the king as distant, surrounded by a coterie of city-dwelling advisers and deaf to the suffering of his people.

“They expect a lot from the government, stemming from the old social contract that was given at the founding of the state,” says Bessma Momani, a Jordanian professor of political science at the University of Waterloo in Canada. “Over time, they’ve been very critical of the reality of their loss of control — partly due to demographics, and partly because the economic hardship in the past few years has been unprecedented . . . Covid exacerbated that.”

During the reign of King Hussein, Abdullah and Hamzah’s father who ruled a turbulent Jordan for 46 years, the government used patronage to mollify — royal visits, grand gatherings that lasted hours and the personal touch between the king and his subjects. Instead of addressing the demands of a modern nation, say analysts, the palace dispensed state jobs, usually in the military, and unaffordable pensions.

By 1989, when Jordan had to resort to an IMF bailout, 90 per cent of workers in the tribal-dominated southern governorates of Ma’an, Karak and Tafilah were employed in the public sector, estimates Tariq Tell, a professor of political science at the American University of Beirut.

It was expensive and unsustainable. Jordan has meagre natural resources and the small nation, squeezed between Iraq, Syria, Israel, the occupied West Bank and Saudi Arabia was buffeted by regional wars, with its demographics transformed by the flow of Palestinians fleeing conflict in Israel, both in 1948 and 1967, and more recently an influx of 600,000 refugees from Syria.

By the time Abdullah took over as king in 1999, the descendants of the tribes that had helped create Jordan were a minority and the kingdom’s economy was on a path of long-term decline, fraying the social contract that kept the tribes quiescent. The 1989 IMF bailout, which required Jordan to cut its government spending, triggered protests in the tribal heartlands. More were to follow, in 1996, 2011 and more recently in 2018.

“The base of the regime — the social pact that has kept it afloat — had been visibly eroding for quite some time, and now it faces serious problems,” says Prof Tell, who has spent years studying the evolution of dissent in Jordan. “[Prince Hamzah] had been testing the waters for a decade, and has gone through this long process to be set up as the man who has got the people’s support.”

Now, after a year of coronavirus, which decimated the tourism sector, vital for jobs and foreign currency earnings, 55 per cent of Jordan’s young people, aged 15 to 24, are unemployed, up from 35 per cent. And the kingdom, which has relied on foreign aid for most of its existence from the US, western financing institutions and once-generous Gulf states, is constrained in its ability to revitalise the economy.

Jordan’s failure to create a vibrant industrial base has become more

apparent — jobs for the mostly unskilled younger population are

scarce.

“[Any] recovery is going to struggle in Jordan,” says Jason Tuvey, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics. “If the government has to resort to cutting subsidies, cutting public sector wages, then we could quite easily see some unrest again.”

Courting the tribes

Prince Hamzah spent years building a loyal base of support among the tribes. He felt like one of them, they say, driving out to their weddings and funerals, joining them in hunting and falconry during the day and in long-drawn out political discussions at night.

A close physical resemblance to his father and his use of classical Arabic allowed him to inhabit the mantle of Hussein’s chosen successor with an ease that defied King Abdullah, say tribal leaders. Lineage matters a great deal in Jordan. Some tribal leaders say they resent that King Abdullah married a Palestinian woman, Queen Rania, and prefer Hamzah’s purely Jordanian ancestry.

“Prince Hamzah was one of us, he was someone very close to our heart,” says one of the leaders, asking for anonymity. “The king is far away — you have to go through so many people to get his attention, and you don’t even know if he has heard your voice.”

Jordanian officials say Prince Hamzah used his popularity to ferret out allies. In a series of text and WhatsApp messages described to the FT, men said to be working for Hamzah would approach tribal leaders secretly, and ask if they would switch their allegiance, from Abdullah. If the answer was yes, quiet meetings would be arranged between them and Prince Hamzah, according to a person briefed on the intercepts.

People close to Prince Hamzah say he was aware of the dangers of his actions as he visited tribes and spoke out against corruption and nepotism. “It became a running joke that he would be thrown in jail,” says one associate. But he insists that while Prince Hamzah had an antagonistic relationship with King Abdullah, he harboured no ambitions to usurp his brother.

“He felt entrusted with his family’s legacy,” the person adds. “His general thinking was, God forbid, if there was a popular uprising in Jordan none of them as a family would survive. The language was ‘do you really think they see a difference between my brother, myself — even people on the periphery of the regime would become persona non grata.’”

According to people briefed on its investigation, Jordanian intelligence has been monitoring Awadallah for several years. An East Jerusalem native, Awadallah rose through Jordan’s political ranks, becoming King Abdullah’s chief of staff by 2015. As finance minister in the early 2000s, he led economic reforms, including privatisation of state assets that were tainted by corruption allegations, and earned the scorn of the tribes for the job losses that resulted.

Since 2018, Awadallah has worked for Mohammed bin Salman who became Saudi Arabia’s crown prince in 2017. According to Jordanian officials, Awadallah and Hamzah have met six times this year. “He was coaching Prince Hamzah, encouraging him, helping him shape his language,” says one.

The intercepts could not be independently verified, and it is not clear if the Jordanian investigation has yielded any additional evidence supporting the allegations of seditious activities.

Most crucially, two Jordanian officials say, Prince Hamzah was in contact with Awadallah on the night the prince met Jordan’s army chief of staff, Major General Yousef Huneiti. The army chief, in a conversation recorded surreptitiously by Prince Hamzah, urged him to curtail his interactions with unnamed palace critics, before the prince strongly suggested he leave.

According to a person familiar with the investigation, minutes later, Prince Hamzah forwarded the recording to Awadallah, with a cryptic note: “The people should know this has happened”. The release of the recording by Prince Hamzah’s lawyer triggered 48 hours of palace turmoil.

Within hours Awadallah was detained in Jordan. A rattled Saudi government publicly expressed its support for King Abdullah and sent four planeloads of officials to Amman. A member of the delegation asked for Awadallah’s release. Jordan declined and he remains in detention.

The person close to Prince Hamzah says he does not believe the royal had a “meaningful relationship” with Awadallah. “I’m not privy to all of his conversations with Bassem, but . . . the sense I got was that Prince Hamzah didn’t really trust Bassem,” he adds.

The government’s narrative of a plot against the king has been treated with scepticism by some in the kingdom and outside.

In a video released after he was placed under house arrest, Prince Hamzah launched a tirade against corruption and “incompetence,” while insisting he was not part of any “conspiracy or nefarious organisation or foreign-backed group”. Saudi officials have also vehemently denied that Riyadh was part of any alleged plot.

“We’re not buying it,” says one western diplomat based in Amman. “It’s easy to make this foreign and scary, to move on from the [core] issue that there is a regime that is not responsive to legitimate criticism.”

Parallel process at the palace

The prince’s approach to the tribes and his criticism of government failures undermined a parallel process being championed by Queen Rania, to position her 26-year-old son Hussein for an eventual coronation. He was named Crown Prince in 2009, a position stripped from Hamzah in 2004.

The young Hussein, also western educated like his father and Prince Hamzah, has 2.7m followers on Instagram, a military background and has been making public appearances designed to boost his image — including at international conferences where he represents the monarchy.

“The King and the Queen are trying to groom him, but it’s not catching — he doesn’t come across [to ordinary Jordanians] yet as a serious contender,” says Daoud Kuttab, a prominent Jordanian radio host and journalist. “And his biggest competition is Prince Hamzah.”

Western diplomats point to another source of friction — after Prince Hamzah’s unsuccessful appeal to the king to be given a larger role in the intelligence services, Queen Rania consolidated her own hold over crucial security apparatus.

The 2019 appointment of Ahmed Husni to head the Mukhabarat, and those of other senior security officials, were championed by the queen, according to officials from both western intelligence and the Israeli military.

“The Mukhabarat is the instrument of Hashemite hegemony,” says Prof Tell. “And if the leadership of the Mukhabarat and the army are now under the direct control of the palace, that means that the queen is a lot more powerful.”

Prince Hamzah’s overtures to the tribes and his positioning as both an insider and a champion of ordinary Jordanians challenge Crown Prince Hussein’s eventual ascent to the throne, says a western diplomat.

“There is a very strong tether between the queen and the security services, and certainly her focus on securing the crown prince’s succession is fairly common knowledge,” adds the diplomat. “This [reaction] absolutely ties into how parts of the system would react to [a threat] from Hamzah.”

Despite his public vow of allegiance, Prince Hamzah remains a potent symbol, and the government has few options to defuse the economic and social pressures that are pushing young Jordanians to openly criticise the king, and reject the palace’s narrative of a foreign-linked seditious plot.

“This is an opportunity for the regime to reconsider how dangerous the situation is, and look for the path to reform,” says a political activist in Ma’an who asked not to be identified. “Things can change slowly, or change suddenly — like in the Arab spring. Until then, Hamzah is like The Man in the Iron Mask.”

[ad_2]

Source link