[ad_1]

This article is the third part of an FT series that examines the future of retail

Japanese billionaire Hiroshi Mikitani is fond of deals that sprout his reputation as the greatest evangelist of e-commerce in a country that has been slower than many to accept.

Rakuten, the Mikitani company founded in 1997 and integrated into Japan’s largest online retailer, has been involved in the Viber messaging app and the site of coupons and refunds in the United States Ebates.

It is a record that explains why his latest agreement has generated this interest. Instead of investing money in a new app, Mikitani agreed in late March to sell an 8% stake in Rakuten to Japan Post, the former state-owned postal service and a powerful symbol of the role of brick and mortar in the country’s $ 5 million economy.

Arriving more than a year after a pandemic that caused the biggest shock to the retail sector in decades, the agreement was used as proof that it is too early to override the role of a network of physical stores to reach the Japanese consumers.

Along with the investment, Rakuten will drastically expand its delivery network and put its brand in front of older buyers who use post offices. Japan Post, for its part, can leverage the knowledge of the online retailer in payments and the use of customer data.

“The essence of this agreement is that Japan Post, which has the largest retail branch, is partnering with Rakuten, which operates the largest digital business,” Hiroshi Takasawa, executive director, told the Financial Times.

If the deal recalls that the country’s retail roots in brick and mortar are deeper than in other major economies, no one is arguing that the pandemic has changed the way Japan buys.

Akio Yoshida, president of Aeon, Japan’s largest supermarket chain, was unequivocal when he addressed investors last month.

“The expansion of Covid-19 has greatly altered consumer behavior, mindset, and value,” he said. “Digital technology has penetrated every part of our lives.”

Standing flat

This poses a radical challenge for a sector that employs seven million people and, over the past decade, has been straddling a heavily divided customer base: a large elderly people doing physical shopping and a cohort of shoppers. younger and with more digital knowledge.

The sale of a stake in Rakuten by Hiroshi Mikitani to the Japan Post is a symbol of the power of the retail sale of bricks and mortars © Keith Bedford / Bloomberg

Demographics are one of the main reasons why a country synonymous with technological innovation has been slower to adopt e-commerce.

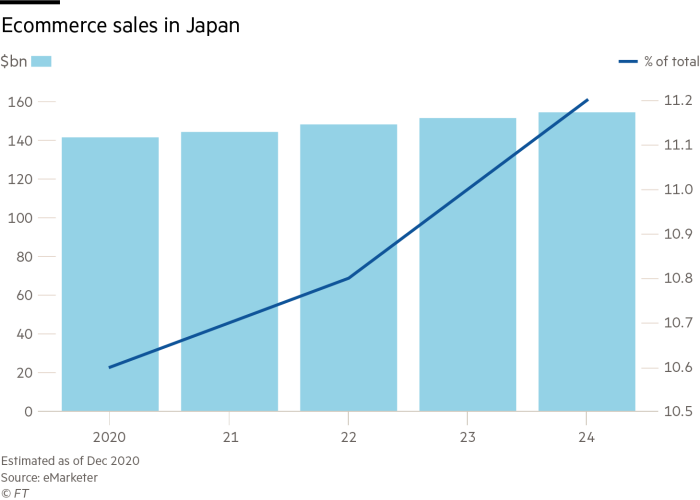

The website will account for nearly 11% of Japan’s retail sales by the end of this year, according to an eMarketer survey. In contrast, the consultancy expects online sales to account for 52% of total in China by the end of the year, 15% in the US and 13% in Western Europe.

But as Japan imposes another state of emergency in an effort to keep the rate of Covid-19 infections low before the Olympics, retailers are unsure of the depth of the effects of the pandemic.

There are signs that some are afraid of being caught as new habits become permanent. Nowhere is it clearer than in the case of Isetan Mitsukoshi, a 348-year-old department store operator who sells everything from luxury bags and bedroom furniture to traditional sweets.

FT Series: Future of Retail Trade

Articles in this series will examine:

Walmart vs. Amazon: The Battle to Dominate Groceries

How China is shaping the future of shopping

Can online markets live up to their hype?

When the government first declared a state of emergency a year ago, the company was forced to quickly develop new habits. Staff went to the Zoom video and messaging line to answer a large number of requests from customers who wanted to be able to buy backpacks online in time for the start of the school year in April.

Since then, the group has developed its own smartphone app that theoretically makes all of the 1 million products sold at its Shinjuku flagship store available online. The app also allows customers to virtually consult sales staff.

“We thought we could offer services that are not available on Amazon or Rakuten if our stylists can offer advice to customers looking for that encouragement before making the decision to buy something. [online]”Said Tomohide Sanbe, senior executive of Isetan Mitsukoshi.

“We are at a point where we need to once again consider the meaning of our existence,” he added.

Yuko Shimomura, who works at a brokerage firm in Tokyo, said the Covid-19 crisis has changed the way we buy.

“I don’t mind physically going to department stores, but I find better deals online,” said Shimomura, who is in his forties.

The end of the game is approaching

It’s not hard to find skeptics who believe Isetan’s carving efforts will prove too little, too late, as the network expands consumers.

“Management underestimated the pace of digital change because of its reliance on physical stores,” Sho Kawano, co-head of Japanese equity research at Goldman Sachs, said of Isetan. “The situation would have been drastically different if Isetan had stepped up digital efforts ten or fifteen years ago. The end of the game is approaching.

Last year, traditional Isetan Mitsukoshi department stores were forced to adapt to the online demand for school backpacks © Noriko Hayashi / Bloomberg

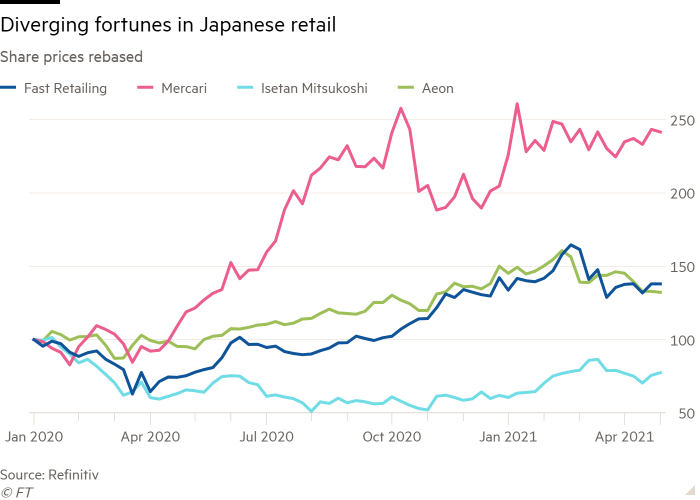

Even before the pandemic, a mixture of complacency and intransigence from some traditional retailers had created an opening that had been taken advantage of by digital rivals such as the Zozo fashion site and the Mercari flea market app. Since the crisis, they have fared even better.

The shares in Mercari, which were made public in 2018, set a new record earlier this year as younger generations of Japanese consumers used the app to sell second-hand clothes, handbags and other accessories. Revenue rose 41% to a record 6 28.6 billion ($ 261 million) in the first three months of the year.

The popularity of the Internet fashion empire Zozotown, owned by Yahoo operator Z Holdings, has also exploded.

Unlike these online specialists, physical stores remain at the heart of Ito-Yokado, one of Japan’s largest supermarket chains. Galvanized by the crisis, however, the company is testing a new approach designed to bridge the gap between its 132 stores and its e-commerce operations.

In September, just as Yoshihide Suga took office as prime minister with the promise of reviving the economy, the company began a supply service that supplied 400 varieties of fresh vegetables, fruits, meat and fish directly to the homes of the old people sounding their orders. by phone.

“We will see more of a world merging online with offline and there will have to be coordination between online supermarkets, delivery services, Ito-Yokado physical stores and convenience stores,” Futoshi Shibata, a senior executive going say in an interview.

As the crisis upsets traditional retailers, there is a company that offers encouragement.

Record benefits

Fast Retailing, owner of the Uniqlo fashion chain, has been hailed as a rare example of a company capable of increasing its online sales while leveraging technology to intelligently operate its now ubiquitous stores..

Domestic sales at Uniqlo’s same store increased 5.6% between September and February over the previous year, while online sales increased 41%. Fast Retailing, which has a market capitalization of $ 86 billion, expects record annual earnings this year.

This unlikely result, according to analysts, is due to the effort Uniqlo has made in both its online and physical operations. Now robots dominate their warehouses, speeding up the selection of goods for delivery. He launched his own cashless payment app, his latest effort to get more valuable data about his customers.

“Whether online or offline, customers ultimately want to buy the products they want at their convenience,” said Xiaozhou Wang, an executive in charge of Fast Retailing’s global e-commerce efforts. “People want to try on their clothes and we need a physical connection with our consumers. But online also has its merits, as it is open 24 hours a day and you have more information about customers. “

Few doubt that long-term Japanese consumers will change more than their online purchases. But as the industry faces its worst losses in decades, the message from shoppers to retailers about future success is unforgivable: improve online and in stores if you want our business.

[ad_2]

Source link