[ad_1]

Riderless horses crashed into an icy lake in the alpine tourist town of St Moritz, causing snow to fall on the faces of men with skis dragged behind them.

In February last year, weeks before the cancellation of public events across Switzerland due to the coronavirus, Credit Suisse brought its most beloved customers to White Turf, an equestrian event of more than a century of antiquity, the exclusively dangerous “skijoring” race that the Swiss bank had sponsored for decades.

Although the seven brave skiers risked their lives at the Credit Suisse Grand Prix, he was one of the guests who posed the biggest threat to the bank: British steel mogul Sanjeev Gupta.

Today, Gupta’s large conglomerate, GFG Alliance, is faltering after the collapse of its main lender Greensill Capital. The metals group is also being investigated by the UK’s serious fraud office. He denies any wrongdoing.

Credit Suisse was known to have indirect exposure to Gupta through Greensill, which packaged loans in banknotes purchased from Swiss bank funds. When Greensill collapsed in March, Credit Suisse was faced with the fact that much of the debt could be bad, including loans to GFG.

What was not known until now, however, is that Credit Suisse also has a significant direct relationship with Gupta.

A number of executives of the Swiss lender have revealed to the Financial Times how their private bankers and world leadership courted the metals mogul, offering him a VIP treatment that extended far beyond the trip to St Moritz.

In establishing a deep relationship with the Indian-born industrialist, Credit Suisse ignored the warnings of concerned corporate customers and their own bankers.

The revelation that Credit Suisse handed Gupta everything from a mortgage on a trophy mansion to a private audience with its then chief executive will further anger its customers who are potentially facing billions of dollars. dollars of losses.

Some of these customers are expected to sue Credit Suisse, alleging failures in the way funds are managed. And Greensill’s problems come as the bank shrinks from another risk management scandal over its work with Archegos, the collapsed family office.

“The decision to finance entrepreneurs like [Gupta] it was at all costs the wrong decision, “said a former Australian business executive of the bank who cited the unease over loans to Gupta as the reason for his resignation. The banker added:” It was a lot of capital to a very risky situation “.

Credit Suisse and GFG declined to comment.

Five star treatment

After spending years courting Sanjeev Gupta, Credit Suisse filed for divorce in late March and asked the courts in the UK and Australia to place several of its main businesses in insolvency.

With $ 1.2 billion to recover on behalf of angry customers, the Swiss bank has other tools at its disposal. Some of Greensill’s Gupta debt facilities benefited from personal guarantees, according to people familiar with the terms, which could allow creditors to pursue the so-called “man of steel” himself.

To that end, Credit Suisse has recently hired private investigators at Kroll to track Gupta’s assets around the world, according to three people familiar with the subject.

While Gupta lasted a half-decade buying companies that built a metal conglomerate with 35,000 employees, he also amassed a personal collection of trophy assets. Purchases ranged from a private jet and a helicopter with matching toilet tail signs to a large £ 42 million London house, owned by his wife’s name.

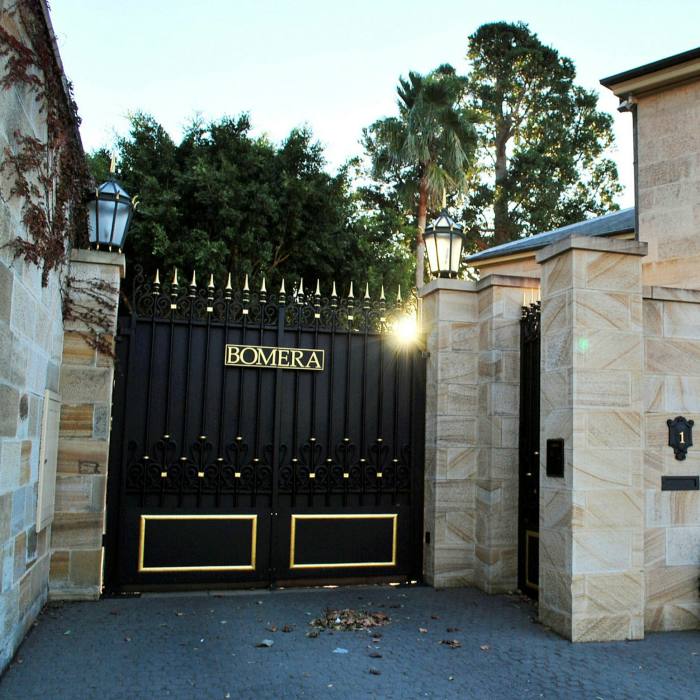

Credit Suisse will not need Kroll’s information services on another of Gupta’s luxury homes – a 19th-century sandstone mansion overlooking Sydney Harbor.

“Credit Suisse provided the mortgage. They were proud of it, “said the former executive. “Going for prime mortgages in Australia was a key strategy.”

Helping Gupta buy the 35 million Australian dollar (US $ 27 million) house, which is owned through a trust overseen by an Australian stockbroker friend, was only part of the service offered by Credit Suisse as a private wealth manager.

The Swiss bank also managed the fortune of Lex Greensill, the 44-year-old Australian founder of Greensill Capital, who was a paper billionaire before his eponymous finance company collapsed.

Lex Greensill’s fortune was also managed by Credit Suisse © Ian Tuttle / Shutterstock

The door of Gupta’s mansion overlooking Sydney Harbor © Getty

Wealth management of controversial entrepreneurs was part of Credit Suisse’s plan. Helman Sitohang, the long-time leader of the Asia-Pacific bank, built a franchise to cater to the region’s richest businessman, taking on some reputational risks.

“We position ourselves as the bank for entrepreneurs,” Sitohang said in February, days before it implemented Greensill Capital. “In Asia, this positioning has resonated well for us.”

Gupta and Greensill even shared the same private banker Credit Suisse: Shane Galligan, one of Sitohang’s biggest rainmakers, who had been on a mission to manage the money of Australia’s wealthiest tycoons.

“If we look at the Asian strategy in terms of supporting very high net worth customers, no one is bigger than him at the private bank,” said a second former Credit Suisse banker. “It simply came to our notice then. That was his thing. “

Galligan made sure Gupta received the full five-star Swiss banking experience. In addition to inviting the steel mogul to the alpine horse racing event, in 2019 he negotiated a coveted meeting with the then chief executive of the bank, Tidjane Thiam.

Galligan and Sitohang were instrumental in avoiding concerns about the bank’s growing entanglements with Gupta and Greensill, according to former Credit Suisse bankers. A person close to the bank said Sitohang was not near Gupta or Greensill.

Another former executive recalled an internal call in 2020 between Galligan, Lara Warner – a risk and compliance officer until he left after the Greensill and Archegos fiascos – and a handful of other bankers to discuss the growing risks surrounding the his business with Greensill.

“There was no sensitivity or appreciation of the risk dimension,” he said. “The tone was purely, ‘We want to bank this enterprising customer.’

Credit Suisse said Sitohang and Galligan declined to comment.

Flight to Zurich

In February 2020, the same month that Credit Suisse welcomed Gupta to St Moritz, British banking regulators contacted the SFO with concerns about his family’s opaque metal conglomerate.

The Swiss bank then received a strong warning. In July 2020, commodity trader Trafigura warned Credit Suisse that the bank’s supply chain financing funds appeared to contain a suspicious bill from Gupta’s business empire. The warning came when the bank was in the middle of a internal review of funds, caused by FT reports on their funds unusual relationship with Greensill shareholder SoftBank.

However, not only did the funds tied to Greensill continue to lend to Gupta, but Credit Suisse considered offering its own balance sheet to the steel mogul.

In October 2020, Gupta unveiled a plan to take control of one of Germany’s oldest and most symbolic industrial concerns: Thyssenkrupp’s more than 200-year-old steel unit.

When the steel tycoon announced the bold offer, had not yet pledged debt financing, but did have letters of support from two well-known financial institutions in its pocket: Greensill and Credit Suisse.

Supporting Thyssenkrupp’s offer was not exceptional. Another former senior executive said Credit Suisse’s investment banking division was “everywhere” at GFG, lured by potential commissions in a seemingly endless chain of appearances, which had also won a mandate over the listing. of his company InfraBuild in Australia. .

However, the quotas never came. Both offers collapsed earlier this year as Greensill began to unravel and threatened to take away GFG.

Greensill’s fate was sealed the last weekend of February, when Credit Suisse made the decision freezes its $ 10 billion reach of supply chain financing funds, having discovered that a key insurance contract supporting the invoice securitization machine had expired.

On the Friday before this fateful decision, Gupta flew to Zurich with his faithful lieutenant Jay Hambro, descendant of a British banking dynasty. Twelve months after the steel baron had enjoyed Credit Suisse’s hospitality at White Turf, he entered the Swiss lender’s headquarters at Paradeplatz with a very different reception.

Gupta and Hambro pressured the bank not to push the funds forward, according to people familiar with the discussions.

This time, however, Credit Suisse was unwilling to welcome its customer, once highly valued.

Additional reports from Owen Walker and Stephen Morris

[ad_2]

Source link