[ad_1]

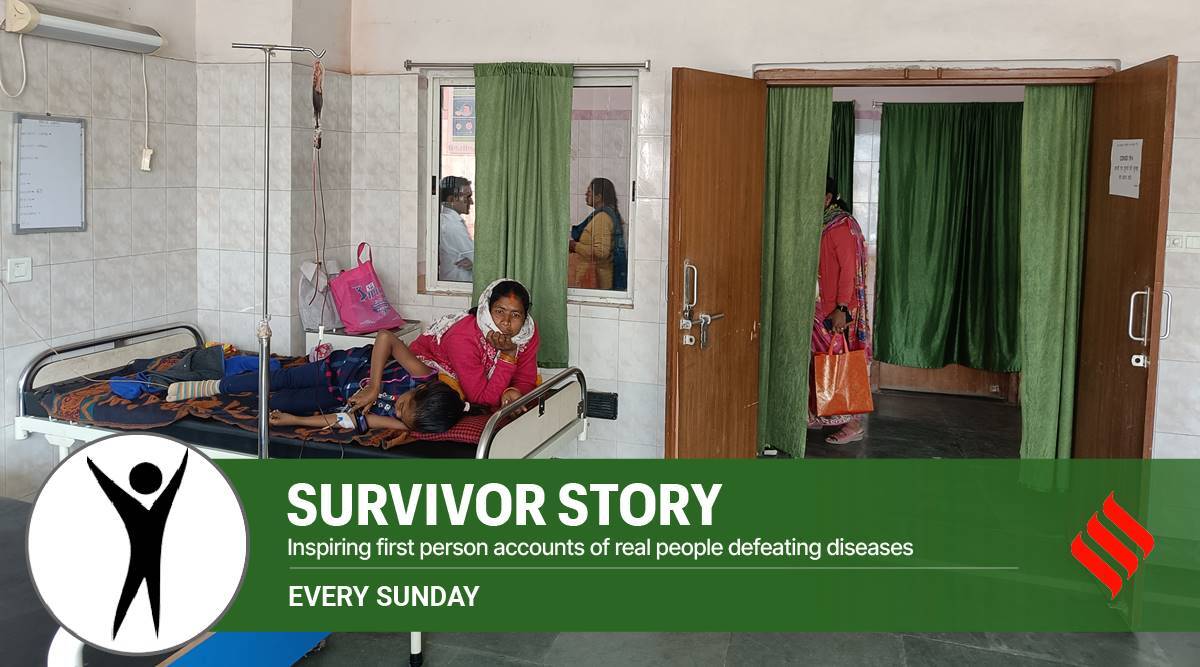

Thirteen-year-old Sati Kumari has no inkling of her life-long medical condition that requires blood transfusion every 15 days. Lying in a daycare ward of the government-run Sadar Hospital in Ranchi district of Jharkhand, she holds her mobile phone watching an animated series, teleporting herself from her trauma. She suffers from Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), an inherited blood disorder where the oxygen-carrying red blood cells (RBCs) are shaped like sickles or crescent moons. When red blood cells are round and flexible, they move easily through blood vessels, ensuring a good blood flow. When they are misshapen, they become rigid and sticky, which can slow down or block blood flow. The disease is widespread among the tribal population in India with one in 86 births among them a confirmed case of SCD.

This is the reason that the Centre has announced a mission to eradicate Sickle Cell Anaemia (SCA), a manifestation of SCD, by 2047. This will entail awareness creation, universal screening of seven crore people in the age group of 0-40 years in tribal areas and counselling through collaborative efforts of Central ministries and State governments. SCA becomes manageable with a comprehensive care programme and blood transfusion. Hydroxyurea is an effective drug for managing SCA, allowing patients to live well into their 60s, but is not always available in remote pockets. Jharkhand has 248 SCD patients, as per the Health Department data. Ranchi district has 62 patients while East Singhbhum district has the highest number at 136. Blood transfusion remains the most trusted form of treatment in the absence of accessible treatments like gene therapy.

Sati’s mother Leela Devi found something amiss when her daughter complained of severe stomach ache as a seven-year-old. As her hands and feet swelled up and the skin yellowed, the family rushed her to a Ranchi hospital where she was diagnosed with the disorder. Since then, the Sadar hospital has become their second address as Sati has to be rushed there after every bout of body pain and exhaustion. Doctors have advised folic acid tablets and Hydroxyurea to maintain healthy levels of red blood cells but Leela Devi wonders why her daughter falls sick more frequently. “Initially, she needed a transfusion once in a couple of months, now we come every 15 days,” she says. This has also come at a huge cost. The family lives in the neighbouring Khunti district and has to use multiple means of transport to reach Ranchi. Every trip costs Rs 200, which Devi says is “extra burden” on her expenses, given her husband’s inability to work due to a mental health condition. “We grow paddy which sustains our family. Sati doesn’t even have a ration card). If the blood was not free, things would have been tough.”

Leela Devi was unaware of the “carrier gene” before she gave birth to her four children. “Children of parents, who are each carriers of a sickle cell gene, are likely to get the disease. The disease is also percolating to non-tribal communities in Jharkhand due to inter-community marriages, although there has not been any study on it,” says Shipra Das Sinha, technical officer, Iodine Deficiency Disorders Cell, who also holds an additional charge of the SCD Cell at the Jharkhand chapter of National Health Mission.

There is a delay in diagnosis as most patients are treated for anaemia and tested only when the problem persists. “That’s because there are overlapping symptoms like weight loss and body ache. We have 11 daycare facilities across Jharkhand catering to SCD, thalassemia and haemophilia with the government spending Rs 45 lakh per facility per year for free testing and medicines. The per drug dosage for haemophilia patients — a blot clot disorder — costs a little over Rs 20,000. In addition, the government also bears the cost of Rs 350 per blood transfusion,” adds Das. National Health Mission Director Bhuvnesh Pratap Singh is working on early detection and is planning for teams to fan out to each village in the tribal belt. “We are also working on issuing cards to people detected with SCD so that they can make informed choices,” he says.

Sati can draw hope from her 27-year-old counsellor, a Masters in commerce, who wishes anonymity. Believing that therapies will be available in the “foreseeable future,” she now helps other SCD patients as an NGO worker.

As a counsellor, she helps patients understand their condition, whether they can be managed medically or whether they need immediate blood transfusion. She also coordinates supplies with blood banks. “I have refused to bow down to the disease and will not let others do so,” says the young woman. She makes Rs 8,000 a month, which hardly supplements her husband’s income given the high cost of treating her own condition. She also gets a disability pension of Rs 1,000 but “it is the satisfaction” of helping others out that keeps her going.

She keeps a watch on her diet and drinks a lot of fluids. “I got a blood transfusion recently and I realised how much daycare means to a lot of people,” she says while attending to 14-year-old Amit Mahli, who watches the blood move through the narrow tube and enter his veins with wonder. “I require blood almost every four months. Once the transfusion is done, I will resume my game of cricket,” says Mahli, a class IX student and a resident of Chanho, 50 km away from Ranchi. His parents are migrant brick kiln workers in Bengal. He keeps looking at his watch, wondering if he will make it to the railway station in time so that he can board the train to Narkopi, the nearest station from his village. The journey lasts an hour but Mahli has mapped his journey far ahead inspired by his counsellor didi. “I want to become a nurse,” he says before getting distracted by the latest mobile update.

[ad_2]

Source link