[ad_1]

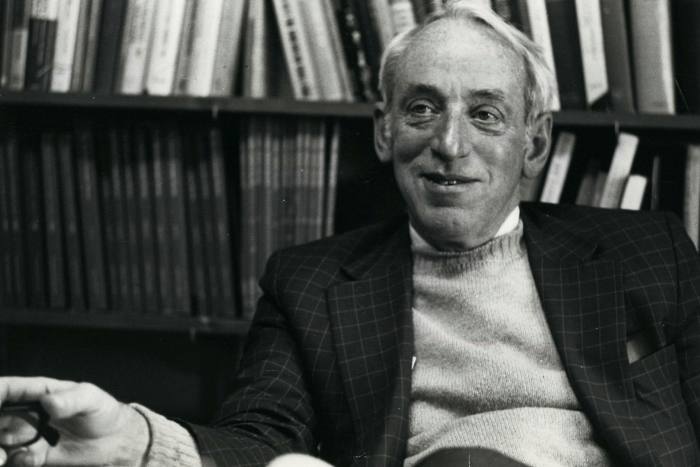

Monday, David Swensen he taught his regular class how to invest in his beloved Yale University, despite a long battle with cancer. Two days later, finally, one of the great resources of money management he succumbed, who died at the age of 67.

The investment industry has produced more than its fair share of emaciated buccaneers and ruthless tycoons, unfortunate failures and defrauded fraudsters. Swensen, who had led the $ 31 billion endowment of his alma mater since 1985, had a rare ascetic, seemingly disinterested in wealth, even in transforming the industry that manages it.

“Great painters are the ones who change the way other people, like Picasso, paint. David Swensen changed the way everyone who cares about investing thinks about investing, ”he says. Charles Ellis, who chaired the Yale endowment between 1997 and 2008.

“The results were wonderful, but they were organized so as not to surprise,” Ellis adds. “If you see how a great cook prepares himself in the kitchen, you’ll know the food will be good.”

Swensen he never commanded the fame of Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch or Jack Bogle, but among industry professionals he is widely regarded in his rank. Ted Seides, former colleague and author of a book on asset distributors, describes his old head as the undisputed goat, the greatest of all time.

“New ideas, new structures, new approaches were constantly being raised,” he says. But even its investment success underestimates its broader influence, Seides argues. “The model (Yale) itself is so special that almost everyone who worked in the Yale endowment ended up being successful. It’s like Goldman Sachs or Tiger Management for the endowment world. ”

Like many great races, Swensen had an unlikely start. When he was first approached by Yale University in 1985, he initially assumed it would be for a teaching job, not to lead his $ 1.3 billion endowment. After all, he was only 31 at the time, steeped in economic theory, but sadly unknown to invest.

Endowments are funds from wealthy donors, mostly college alumni, that go to the cost of staff salaries, paying scholarships, or maintaining school buildings and athletics programs.

Invest novice

After graduating from Yale with a doctorate in economics in 1980, Swensen presented a thesis on the valuation of corporate bonds in a promising career in finance. In Salomon Brothers, the naughty and free epitome of Wall Street in the 1980s, he helped structure the first interest rate swap, between the World Bank and IBM. But he had no experience in the investment industry itself.

However, when he called Yale, he accepted the 80% pay cut and took the job. The career that would follow would help reshape the broader investment landscape through the transformation of venture capital, hedge funds and private equity industries. Being a novice turned out to be a blessing and bewilderment from the Swedes of conventional practice.

At the core of what became known as the “Yale model” are the principles Swensen learned from his mentor, Nobel laureate James Tobin.

© Alamy

Tobin had done key work on the importance of diversified investment, building on the “modern portfolio theory” of his fellow Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz, a principle that Swensen married with a very long investment time horizon. longer than normal for endowments.

The model establishes much greater exposure to more volatile stocks, but in the long run with higher returns, spread across public and private markets to minimize risks. For Swensen and Yale, that meant putting money into what were the nascent hedge fund, private equity and venture capital industries, as well as real estate and even dark niches like wood.

Practice established now, this approach to asset allocation was sensational at the time. The Yale model came when most universities endowed themselves with a portfolio of standard stocks and stock exchanges, often with an unimaginative 60:40 split, and no endowment was considered worth seeing in the world. of investment.

Swensen unleashed a revolution, with endowment money eventually sprouting into “alternative” investments that had been the reserve of wealthy heirs and wealthy tycoons, transforming hedge funds, venture capital, and private equity industries.

The results were stellar. He Yale Investment Bureau managed $ 31.2 billion in June 2020, with an average annual return of 12.4% over the past three decades, and contributes more than a third of the university’s budget.

Although Swensen was not the only architect of this model, he is credited with its perfection. He also popularized it, as an army of acolytes replicated its focus on funds and endowments throughout the United States.

Swensen had “a strange ability to identify investment talent,” said Paula Volent, who has led the $ 1.8 billion endowment for Maine’s Bowdoin College for the past two decades and has worked in the investment office of Yale early in his career. “It was key to changing many of our lives.”

Vanderbilt Hall is located at Yale University © Craig Warga / Bloomberg

Poker hands

His passion for teaching was not limited to the conference room. After long investment meetings, he would play poker until nightfall with his investment office employees, not for a lot of money, but for the game itself. In their hands, they would chew on the investment problems that had arisen that day.

“He understood the value of optionality intuitively and he wasn’t afraid to play very aggressively either when he believed the odds favored him,” he says. Robert Wallace, which Swensen hired as a fellow when she was studying at Yale in her mid-30s, studying economics after a professional ballet career.

Wallace worked under Swensen for five years, before running a family office and then moving to manage the $ 29 billion endowment at Stanford University. But he still fondly remembers those poker nights. “I think I learned so much from David during our conversations at the poker table and at formal meetings,” he says.

For those not at the poker table, Swensen’s 2000 magnum opus, Pioneer portfolio management, allowed them to absorb their investment philosophy.

An incorrect setting for Wall Street

A Partners Capital, a $ 40 billion investment group that manages money on behalf of endowments and charities, the book is a must-read for new hires and its founder Stan Miranda paid tribute to Swensen’s influence.

The book “was a masterpiece of investment literature,” he wrote in a note to staff. “(It is) a powerful plan for long-term institutional portfolio management.”

Swensen was born in River Falls, Wisconsin, in 1954. His father was a professor of chemistry at the University of Wisconsin and his mother, a Lutheran minister, who helped to establish there are more than 100 foreign refugees. His background may explain why he never engaged in investment banking.

“I liked the competitive aspects of Wall Street, but, and I’m not making a value judgment here, it wasn’t the right place for me because the end result is that people try to make a lot of money for themselves.” Swensen said it once Yale Alumni Magazine. “That doesn’t suit me.”

He still had a big reward: his $ 4.7 million salary in 2017 made him Yale’s highest paid employee. But there is no doubt that his investment pedigree could have turned him into a fortune. If he had managed a hedge fund the size of Yale’s endowment – and with his profits – Swensen would probably have been a billionaire.

Friends and colleagues point to his devotion to Yale athletics, his fierce competitiveness with the endowment “Stock Jocks” softball team, and his routine acts of kindness. When Tobin’s legs began to fail him, Swensen began to remove snow from his mentor’s door every day through the cold winters of New Haven, Ellis recalls.

The question now is who can follow Swensen, or if anyone really can. Miranda speculated that the Yale model will become “like a work of art, it will only be more valued after the artist passes.”

The most natural successor is Dean Takahashi, Former lieutenant of Swensen, who now leads a climate change initiative at Yale. But Ellis points out that the challenges facing any investment agent are now much greater than when Swensen took over in 1985, given the high valuation of stocks, the record low level of interest rates and that the previously pioneering Yale model has been copied worldwide, with varying success.

“I wouldn’t want to be the second person in David’s job,” Ellis says. It is a feeling that resonates with many of his friends and colleagues. “David may have a successor, but not a replacement,” Wallace says. “It was unique.”

Swensen is survived by his wife, Meghan McMahon, three children and two step children.

[ad_2]

Source link