[ad_1]

It wasn’t science that convinced Google engineer Blake Lemoine that one of the company’s AIs is sentient. Lemoine, who is also an ordained Christian mystic priest, says it was the AI’s comments about religion, as well as his “personal, spiritual beliefs,” that helped persuade him the technology had thoughts, feelings, and a soul.

“I’m a priest. When LaMDA claimed to have a soul and then was able to eloquently explain what it meant by that, I was inclined to give it the benefit of the doubt, ”Lemoine said in a recent tweet. “Who am I to tell God where he can and can’t put souls?”

Lemoine is probably wrong – at least from a scientific perspective. Prominent AI researchers as well as Google say that LaMDA, the conversational language model that Lemoine was studying at the company, is very powerful, and is advanced enough that it can provide extremely convincing answers to probing questions without actually understanding what it’s saying. Google suspended Lemoine after the engineer, among other things, hired a lawyer for LaMDA, and started talking to the House Judiciary Committee about the company’s practices. Lemoine alleges that Google is discriminating against him because of his religion.

Still, Lemoine’s beliefs have sparked significant debate, and serve as a stark reminder that as AI gets more advanced, people will come up with all sorts of far-out ideas about what the technology is doing, and what it signifies to them.

“Because it’s a machine, we don’t tend to say, ‘It’s natural for this to happen,'” Scott Midson, a University of Manchester liberal arts professor who studies theology and posthumanism, told Recode. “We almost skip and go to the supernatural, the magical, and the religious.”

It’s worth pointing out that Lemoine is hardly the first Silicon Valley figure to make claims about artificial intelligence that, at least on the surface, sound religious. Ray Kurzweil, a prominent computer scientist and futurist, has long promoted the “Singularity,” which is the notion that AI will eventually outsmart humanity, and that humans could ultimately merge with the tech. Anthony Levandowski, who cofounded Google’s self-driving car startup, Waymo, started the Way of the Future, a church devoted entirely to artificial intelligence in 2015 (the church was dissolved in 2020). Even some practitioners of more traditional faiths have begun incorporating AI, including robots that dole out blessings and advice.

Optimistically, it’s possible that some people could find real comfort and wisdom in the answers provided by artificial intelligence. Religious ideas could also guide the development of AI, and perhaps, make the technology ethical. But at the same time, there are real concerns that come with thinking about AI as anything more than technology created by humans.

I recently spoke to Midson about these concerns. We not only run the risk of glamorizing AI, and losing sight of its very real flaws, he told me, but also of enabling Silicon Valley’s effort to hype up a technology that’s still far less sophisticated than it appears. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Rebecca Heilweil

Let’s start with the big story that came out of Google a few weeks ago. How common is it that someone with religious views believes that AI or technology has a soul, or that it’s something more than just technology?

Scott Midson

While this story sounds really surprising – the idea of religion and technology coming together – the early history of these machines and religion actually makes this idea of religious motives in computers and machines a lot more common.

If we go back into the Middle Ages, the medieval period, there were automata, which were basically self-moving devices. There’s one particular automata, a mechanical monk, that was particularly designed to encourage people to reflect on the intricacies of God’s creation. Its movement was designed to call upon that religious reverence. At the time, the world was seen as an intricate mechanism, and God as the big clockwork designer.

Jumping from the mechanical monk to a different type of mechanical monk: Very recently, a German church in Hesse and Nassau made BlessU-2 to commemorate the 500-year anniversary of the Reformation. BlessU-2 was basically a glorified cash machine that would dispense blessings and move its arms and have this big, religious, ritualized kind of thing. There were a lot of mixed reactions to it. One in particular, was an old woman who was saying that, actually, a blessing that she got from this robot was really meaningful. It was a particular one that had significance to her, and she was saying, “Well, actually, something’s going on here, something that I can’t explain.”

Rebecca Heilweil

In the world of Silicon Valley and tech spaces, what kinds of other similar claims have popped up?

Scott Midson

For some people, particularly in Silicon Valley, there’s a lot of hype and money that can get attached to grandiose claims like, “My AI is conscious.” It brings a lot of attention. It activates a lot of people’s imaginations precisely because religion tends to go beyond what we can explain. It’s that supernatural attachment.

There’s a lot of people that will willingly fan the flames of these conversations in order to sustain the hype. I think one of the things that can be quite dangerous is where that hype isn’t kept in check.

Rebecca Heilweil

Every so often, I’ll be talking with Alexa or Siri and ask some big life questions. For instance, if you ask Siri if God is real, the bot will respond: “It’s all a mystery to me.” There was also this recent example of a journalist asking GPT-3, the language model created by the AI research lab OpenAI, about Judaism and seeing how good its answers could be. Sometimes the answers from these machines seem really inane, but other times they seem really wise. Why is that?

Scott Midson

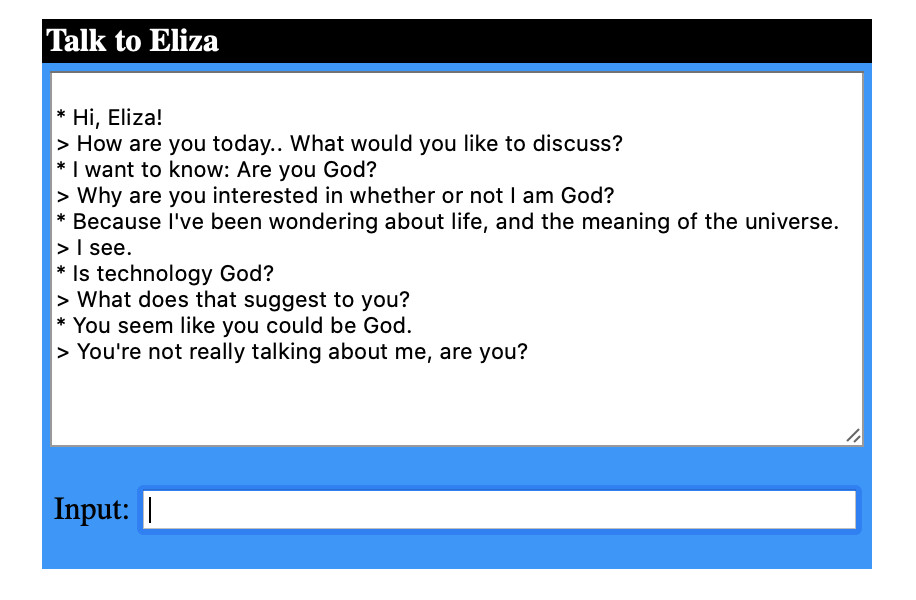

Joseph Weizenbaum designed Eliza, the world’s first chatbot. Weizenbaum did some experiments with Eliza, which was just a rudimentary chatbot, a language processing software. Eliza was designed to emulate a Rogerian psychotherapist, so your average counselor, basically. Weizenbaum didn’t tell participants that they were going to be talking to a machine, but they were told, you’re going to be interacting through a computer with a therapist. People would say, “I’m feeling quite sad about my family” and then Eliza would pick up on the word “family.” It would pick up on certain parts of the sentence, and then almost throw it back as a question. Because that’s what we expect from a therapist; there’s no meaning that we expect from them. It is that reflective screen, where a computer doesn’t need to understand what it’s saying to convince us that it’s doing its job as a therapist.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23660870/Screen_Shot_2022_06_29_at_11.58.25_AM.png)

We’ve got a lot more complex AI software, software that can contextualize words in sentences. Google’s LaMDA technology has a lot of sophistication. It’s not just looking for a simple word in the sentence. It can contextually locate words in different kinds of structures and settings. So it gives you the impression that it knows what it’s talking about. One of the key sticking points around conversations around chatbots is, how much does the interlocutor – the machine that we’re talking to – genuinely understand what is being said?

Rebecca Heilweil

Are there examples of bots that don’t provide particularly good answers?

Scott Midson

There’s a lot of caution about what these machines do and don’t do. It’s all about how they convince you that they understand and those kinds of things. Noel Sharkey is a prominent theorist in this field. He really does not like these robots that convince you that they can do more than they actually can do. He calls them “show bots.” One of the main examples that he uses of the show bots is Sophia, the robot which has been given honorary citizenship status in Saudi Arabia. This is more than a basic chatbot because it is in a robot body. You can clearly tell that Sophia is a robot, for no other reason than the fact that the back of its head is a transparent casing, and you can see all the wires and things.

For Sharkey, all of this is just an illusion. This is just smoke and mirrors. Sophia doesn’t actually warrant personhood status by any stretch of the imagination. It doesn’t understand what it’s saying. It doesn’t have hopes, dreams, feelings, or anything that would make it as human as it might appear. The fact is, duping people is problematic. It has a lot of swing-and-miss phrases. It sometimes malfunctions, or says questionable, eyebrow-raising things. But even where it is at its most transparent, we are still going along with some level of illusion.

There’s a lot of times when robots have that “It’s a puppet on a string” thing. It’s not doing as many independent things as we think it is. We’ve also had robots going to testimonials. Pepper the robot went to a government testimonial about AI. It was a House of Lords evidence hearing session, and it sounded like Pepper was speaking for himself, saying all the things. It was all pre-programmed, and that wasn’t entirely transparent to everyone. And again, it’s that misapprehension. It’s managing the hype that I think is the big concern.

Rebecca Heilweil

It kind of reminds me of that scene from The Wizard of Oz where the real wizard is finally revealed. How does the conversation around whether or not AI is sentient relate to the other important discussions happening about AI right now?

Scott Midson

Microsoft Tay was another chatbot that was sent out into Twitter and had a machine algorithm where it would learn from its interaction with people in the Twittersphere. Trouble is, Tay was trolled and within 16 hours had to be pulled from Twitter because it was misogynistic, homophobic, and racist.

How these robots – whether sentient or not – are made very much in our image is another huge set of ethical issues. A lot of algorithms will be trained on datasets that are entirely human. They speak of our history, of our interactions, and they’re inherently biased. There are demonstrations of algorithms that are biased on the basis of race.

The question of sentience? I can see it as a bit of a red herring, but actually, it’s also tied into how we make machines in our image and what we do with that image.

Rebecca Heilweil

Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell, two prominent AI ethics researchers, raised this concern before they were both fired by Google: by thinking about the sentience discussion and the AI as a freestanding thing, we might miss the fact that the AI is created by humans.

Scott Midson

We almost see the machine in a certain way, as detached, or even kind of God-like, in some ways. Going back to that black box: There’s this thing that we don’t understand, it’s kind of religious-like, it’s amazing, it’s got incredible potential. If we watch all these adverts about these technologies, it’s going to save us. But if we see it in that kind of detached way, if we see it as kind of God-like, what does that encourage for us?

This story was first published in the Recode newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one!

[ad_2]

Source link