[ad_1]

Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has never been one to shy away from making bold promises while vowing to revive the Arab world’s most populous state. But in March, he delivered a prediction that was audacious even by his standards.

Speaking at a military event, he said the inauguration of a “New Administrative Capital” covering a swath of desert equal to the size of Singapore, would represent the “birth of a new state”. His words will soon be put to the test.

In August, civil servants will begin making the 45km transition from ministries in downtown Cairo to the new capital, where construction workers are putting the finishing touches to the $3bn “government district”. The aim is to have 55,000 staff operating out of more than 30 huge new ministries by the end of the year. Ultimately, with private developments alongside military projects, the goal is to have 6.5m people living in the city.

The project — forecast to cost $45bn when it was launched six years ago — embodies Sisi’s vision of development and how it should be done: the military is unabashedly front and centre and it is being built on a pharaonic scale. Sisi insists it represents the “declaration of a new republic” even as sceptics consider it a vanity project a country with more urgent priorities can ill-afford.

The new capital east of Cairo is the flagship infrastructure project out of thousands the military has taken charge of since the former army chief seized power in a 2013 coup.

As a result construction and real estate, along with energy, have been key drivers in reviving the moribund economy. They have enabled Egypt to boast the Middle East’s highest rates of growth in gross domestic product — recording more than 5 per cent per annum in the two years before Covid hit. But just as the administrative capital provokes contrasting reactions, so too are some Egyptians asking whether the economic successes cheered by the president’s supporters are more mirage than reality.

“The economy looks healthy from the outside, but if you poke around it’s all built on quicksand,” says an Egyptian academic.

‘They have yielded results’

At the core of the concerns is that the expansion of the military’s role in the state and the economy is crowding out the private sector and scaring away foreign investors. “The real fear people have is you go in and set up a project and the military replicates that project next door and undercuts you,” says an Egyptian economist.

Yet Sisi and his loyalists make no apologies for his deployment of the military — Egypt’s most powerful institution and the one entity the president trusts — into all aspects of the economy.

“The army can enhance the economy . . . they are very disciplined, less corrupt,” says Khaled el-Husseiny Soliman, a retired brigadier general who is spokesman for the Administrative Capital for Urban Development, a company majority owned by the military and in charge of the new capital project. “In the Egyptian military we all say the battalion or platoon equals the commander. The state reflects the leadership . . . I believe now we have a leader.”

Some Egyptians say they understand why Sisi turned to the military after taking power, following three years of tumult in the wake of the 2011 uprising that ended Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. He inherited an economy broken by political upheaval, civil strife and terrorist attacks that spooked domestic and foreign investors into inertia.

By 2016, dwindling foreign reserves and dollar shortages forced Cairo to turn to the IMF for a $12bn loan. As part of the package, the regime allowed the Egyptian pound to devalue, causing the currency’s value to halve, further damaging confidence and eroding purchasing power. Soaring inflation and sky-high interest rates have been additional impediments to private investment.

“[The military] have tackled areas never tackled and yielded some results,” says an Egyptian banker. “The fact they can do anything any time in your area does stop people investing. But the market is bigger than any single entity.”

But eight years after Sisi seized power, there is a growing fear that the military’s muscular economic expansion will prove irreversible. Economists say the activity is not generating sufficient productive jobs to tackle rampant youth unemployment and poverty in the nation of 100m people.

The employment rate has fallen from 44.2 per cent among working age Egyptians in 2010 to 35 per cent in the second quarter of last year, even as an estimated 800,000 graduates annually enter the jobs market, according to a report by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation. And the demographic and social pressures are only going to build as the fertility rate of 3.5 children per Egyptian woman means the population will swell by 20m people over the next decade.

“We have growth of 5 per cent, but 2.5 per cent comes from minerals [oil and gas] which brings in money but doesn’t create employment, which is the only thing that’s going to save us,” the academic says. “The other 2.5 per cent is real estate [and construction], which is fictitious employment. Once you stop building, there are no jobs.”

The World Bank says private investment picked up slightly in 2019, but adds that its weighting in the economy was still below historical averages and “considerably lower” than peer countries such as Jordan and the Philippines.

Even staunch Sisi supporters murmur doubts as businesses are forced to contend, or even compete, with the military, which controls much of Egypt’s land, can use conscript labour, is exempt from income and real estate taxes and answers only to Sisi, the commander-in-chief.

“Sisi is loved by everybody, including myself, and he’s a nationalist who does what he thinks is best for the country. But that does not mean he’s right all the time,” says an Egyptian investment banker. “He should consult others; he’s ill-advised.”

He laments that the myriad structural problems that long hindered private sector growth, from corruption and red tape to poor logistics, still deter investment. And “now there’s crowding out by the state — it’s the army and the government in every single sector”, he says. “You name it.”

Check on executives

Most in the business community welcomed the new regime after Sisi ended the brief, divisive reign of the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood government. The chaotic period reinforced many Egyptians’ belief that stability came above all else. Three years after the coup, executives, western bankers and the IMF also applauded when Sisi pushed through tough monetary and fiscal reforms, including cutting subsidies and the state’s wage bill, while increasing VAT to secure the $12bn loan.

But Sisi never reciprocated the welcome he received from business. At an early meeting with Egyptian executives, the president told them they had benefited under Mubarak and needed to give back — and donate E£100bn to the regime, according to businessmen who donated.

Many suspect Sisi entered the presidency distrusting the private sector and disgusted by the cronyism rife during the Mubarak era. He is also wary of businessmen becoming too powerful and politically influential, viewing it as one of the ingredients that fuelled the 2011 uprising, analysts say.

“From the outset he wanted to use the military in project management and as a tool for large infrastructure projects. My instinct tells me he would rather have left it like that,” says an Egyptian businessman. “But then he felt snubbed by the old, large private sector, which he thought couldn’t be trusted and may constitute some form of political opposition. Then comes the push for the military to invest across all industries.”

The military has been the bedrock of the state since Gamal Abdel Nasser’s 1952 coup. Its business interests deepened after the 1979 peace accord with Israel redefined the army’s role. But, until Sisi, it remained largely in the shadows.

After initially surrounding himself with military advisers, Mubarak, a former air force officer, gradually courted civilians who began liberalising the economy. Under Sisi, Egypt has transitioned from a police state to a military-led state, analysts say.

“You always had generals in ministries, but in Mubarak’s time they were in the basement,” the academic says. “Now the one who decides whether you stamp this piece of paper is a general.”

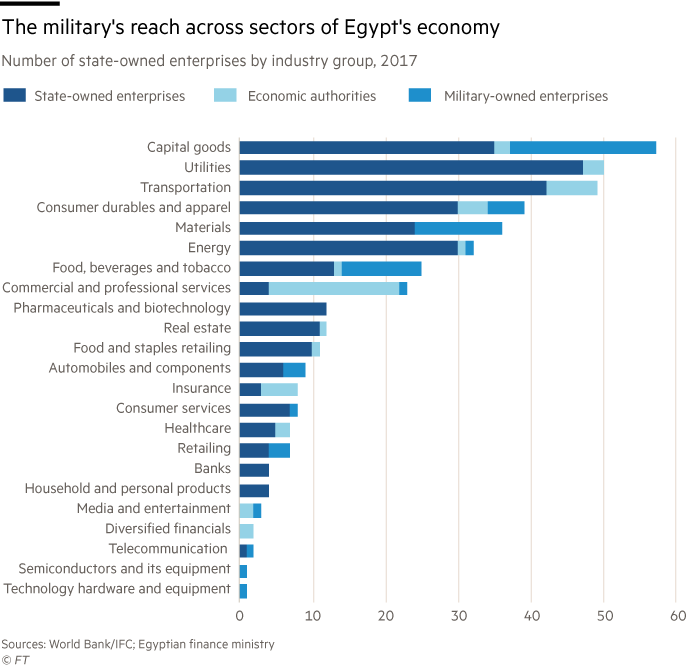

The army’s tentacles stretch across the economy, from steel and cement to agriculture, fisheries, energy, healthcare, food and beverages. Not even the media has been spared, as entities related to state security agencies have taken over newspapers, TV channels and production houses.

A lack of transparency makes it difficult to determine the full scale of the army’s economic role. Last June, prime minister Mostafa Madbouly said Egypt had completed projects worth E£4.5tn ($287bn) over six years. The army’s engineering authority commander, Ihab al-Far, said the funds were spent on 20,000 projects, adding that the military invested a further E£1.1tn on 2,800 schemes built by the army. Sisi told the FT in 2016 that the army’s businesses were to ensure the country’s self-sufficiency, not compete with the private sector.

There are 60 companies affiliated to military entities operating in 19 of the 24 industries of the Global Industry Classification Standards, an industry taxonomy body, according to the World Bank report. The military’s National Service Projects Organisation (NSPO) controls 32, a third of which were established after 2015.

Yezid Sayigh, a senior fellow at the Malcolm H Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, estimates that in 2019 military-affiliated entities generated income of $6bn-$7bn.

But it is their reach across the economy that is critical. “The real questions are what are the net impacts on public finances, on the private sector, on the volume of foreign investment and where it goes,” he says. “The income is significant and no doubt creates a stake the military will defend at almost any cost, but for now it’s the role that’s most crucial.”

The most visible example of the military’s impact on the private sector has been in cement. The army opened a new $1.1bn plant in 2018 that added 12m tonnes of annual production capacity to the sector. It did so even as demand for cement was on the slide and the sector was operating far below capacity.

The military now accounts for 24 per cent of production capacity, industry officials say. Its intervention pushed several private sector players towards collapse. It prompted some investors to consider selling, but no buyers were willing to enter the oversupplied market, the officials say.

The military’s intervention appears to have been based on a false assumption that Egypt’s cement consumption would soar. It is a narrative that fits with what Michael Wahid Hanna, an analyst at the International Crisis Group, describes as Sisi’s “impulse” to turn to the military “to get things done”.

“It gathers a momentum of its own,” Hanna says. “It’s hard to say there’s a well-conceived economic vision as opposed to an impulse and suspicion.”

He believes one reason for the phenomenon is the fact that Sisi – who leads the most oppressive regime since Nasser – has no institutional base in society. “They don’t have any sort of party structures, which is part of the reason why they are so reliant on the military and the public sector,” Hanna adds. “Their project is to cripple the civilian-led political order.”

Investment cycle

Ayman Soliman, chief executive of The Sovereign Fund of Egypt, insists the government is cognisant of investors’ concerns and is taking action to address them. The sovereign wealth fund is overseeing the privatisation of two of 10 companies the military-owned NSPO was willing to dispose of: Wataniya, which runs about 200 service stations, and Safi, a water bottling and food company.

“This is to open the space for the private sector to come in, step up and acquire those assets if they want,” Soliman says. “The economy needs to have the private sector dominate the investment cycle. The government is paying so much to fuel growth, but this should not be sustainable.”

Egypt has been struggling to balance its books for years as it grapples with yawning current account and budget deficits. Subsidies, public sector wages and foreign interest payments account for 110 per cent of revenue, according to Goldman Sachs.

As the coronavirus pandemic shuttered the vital tourism sector and investors pulled at least $13bn from its debt and equity markets, Cairo was forced to turn once more to the IMF last year. It secured more than $7bn in loans, raising Egypt’s total outstanding credit to the fund to $19bn — the second largest amount after Argentina.

Economists say Egypt’s public finances displayed resilience during the pandemic, and Cairo was able to tap capital markets in difficult times. But its debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to rise to 93 per cent in the financial year 2020/21, according to the IMF, while Cairo’s three key sources of foreign currency are all vulnerable to external factors — tourism, remittances and portfolio inflows into local debt.

The latter depends on high interest rates, which act as yet another brake on private investment. “You cannot keep relying on short-term inflows and betting on remittances and tourism,” says the economist, adding that the regime must allow the private sector to breathe, incentivise industry and strengthen exports.

The Egyptian businessman hopes the cement debacle will be a lesson the regime heeds: the government has been talking to cement companies about their concerns in recent weeks after some threatened legal action. “There is going to be a price of the legacy, and there will be an evolution, the question is how long will it take and how expensive will it be,” he says.

But Hanna says it is hard to imagine Sisi unwinding the military’s role, given the vested interests.

“He has his detractors within the institution itself, he has purged people, he has favoured military intelligence and so he clearly has to rely on some of this largesse and patronage within the military,” he says. “Is this the fight he’s going to pick? One, his world view doesn’t lead him to, and two, his sense of self-preservation doesn’t either.”

[ad_2]

Source link