[ad_1]

Can Big Tech enjoy government-backed bond market borrowing costs? An analysis by the IMF’s Nordin AB and the ECB’s Exert Michel-Flores suggests that investors are demanding artificially low risk premiums from Amazon and Alphabet on the assumption that no sane government would allow them to fail.

This is not the least bit annoying given how such companies minimize the taxes they pay. The bond market’s implicit acknowledgment that Big Tech is a colossal failure should set off regulatory alarm bells. But first, to a summary of the findings:

On the macro side, the paper suggests that large tech companies will gain funding – by an average of 30bps – from 2014 to 2021. Our estimates are that (indirect) subsidies are around $2 billion per year. And it has been steadily increasing, especially during most of the observed periods due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the scale of the speculation remains, the expected support from the government appears to be embedded in the option-adjusted bond yields issued by large US technology firms. In other words, we find that the bonds of Big Tech institutions are expected to (probably) protect the government from bankruptcy during a technology downturn, and thus underperform. This expectation of government support is a clear cut for large tech firms, allowing them to borrow at subsidized rates.

Abdi and Mikel-Flores note that there are many other reasons why bonds issued by TBTF-rated companies may trade at such competitive spreads.

Larger companies in most industries receive more bond financing than smaller companies. They will also benefit from economies of scale, easier money supply and more liquid bonds, the pair write. However, there is still “a significant amount of funding for technology companies after controlling for the impact on credit spreads for non-tech companies,” he said.

Companies like Alphabet and Apple aren’t the first to enjoy subsidies. Abidi and Mikel-Flores argue that Big Tech is as structurally important today as the big banks were before 2008 – although the amount of funding they faced then remains up for debate.

A paper suggests that “indirect government guarantees” can yield up to 1.21 per cent of funding benefits for large banks. Less surprising in its conclusions is a 2013 Goldman Sachs report:

Within the universe of bond-issuing US banks, the six biggest banks received little funding – an average of just 6bp – from 1999 until the start of the financial crisis in mid-2007. Large funding deficits for most of 2011 and 2012. Even today, the bonds of these six banks have a loss of approximately 10bp on the bonds of other banks.

In any case, institutions deemed too big to fail have a nasty habit of testing the theory. The term may even be self-fulfilling. As a boss, you like to risk more if you think the government can save you. Abidi and Michel-Flores say that implicit guarantees “may create distortions of competition, reduce market discipline and further increase economic stress in the future.”

So it’s worth planning for a “tech crash” – even if we don’t know what one will look like. Possible triggers include cyberattacks targeting big tech cloud computing software, which is growing in finance.

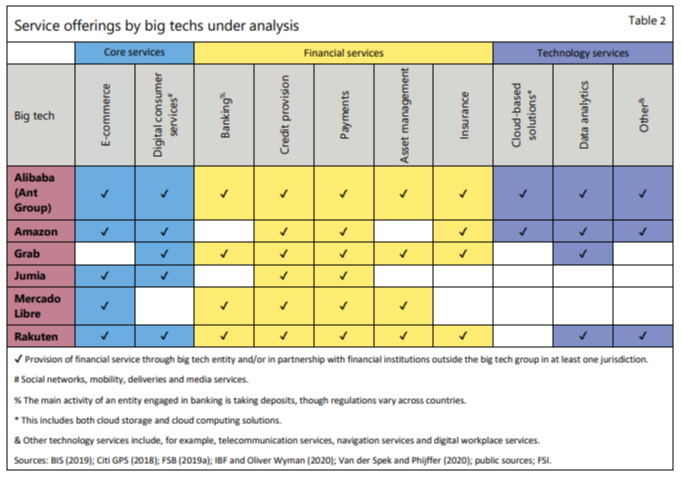

The expansion of Big Tech © Bank for International Settlements

Any technological disruption “would have a significant impact on global foreign exchange, financial markets and data integrity,” Abidi and Mikel-Flores said. “A Big Tech failure or service failure could pose a significant threat to the continuity of financial services, which could adversely affect markets, consumers, financial stability and the economy as a whole.”

That, and the fact that we all pay $2 billion a year for Big Tech’s R&D budget, seems reason enough for regulators to tighten the ropes.

[ad_2]

Source link