[ad_1]

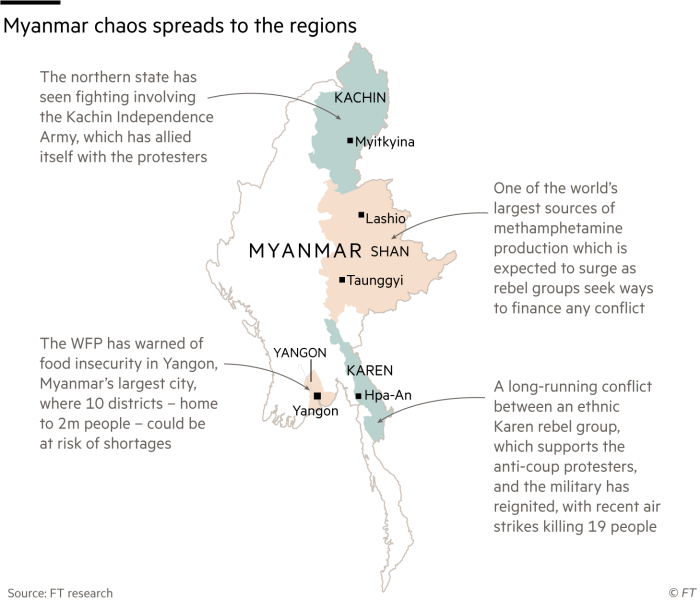

Myanmar air force jets strafed, bombed and shelled villages, schools and rice barns over four nights, killing 19 and displacing up to 30,000 people, according to the Karen National Union, a rebel group in the eastern state bordering Thailand. The military struck after the armed wing of the KNU over-ran one of its bases and killed 10 soldiers, on the day the ruling junta was celebrating Armed Forces Day in the capital Naypyidaw.

The minority Karen people are no strangers to violence. They have been fighting the Tatmadaw, or Myanmar military, for most of the past seven decades since the country gained independence from Britain. But the fighting had eased, if not ended, since a 2012 ceasefire, until the air strikes — the first in the area for a quarter of a century.

The military was seeking swift retaliation, but another factor in their decision was the presence in Karen of activists who had fled the cities — the main protest centres since the February 1 military coup — and taken shelter in the state.

The bombardment that started on March 27 was brutal. Thousands of people, mainly women and children, fled the shelling on boats across the Salween river into Thailand, where authorities pushed them back. It was also a very explicit sign that the conflict in Myanmar is spreading.

What started as a domestic political crisis caused by the military’s toppling of Aung San Suu Kyi’s government has quickly escalated. First into a human rights emergency as troops shot and killed unarmed protesters and more recently into something resembling a civil conflict, as protesters begin to arm themselves with crude improvised weapons and build alliances with better armed ethnic groups in minority areas.

Michelle Bachelet, the UN human rights chief, warned last week that she feared Myanmar was “heading toward a full-blown civil conflict”.

“There are clear echoes of Syria in 2011,” Bachelet said. “There, too, we saw peaceful protests met with unnecessary and clearly disproportionate force. The state’s brutal, persistent repression of its own people led to some individuals taking up arms, followed by a downward and rapidly expanding spiral of violence.”

Karen leaders want urgent action: sanctions imposed against the junta and a no-fly-zone to protect their people from air attacks. Fighting has also broken out in other regions including northern Kachin state, where another armed group has overrun police and military outposts, and the military has responded with deadly air strikes.

“The world needs to put in very strong and effective sanctions, to block dollar and euro transactions so the coup makers can’t use them any more,” Padoh Saw Taw Nee, the head of the KNU’s foreign affairs department, says. “But the world is still reluctant to do it.”

The growing violence is worrying Myanmar’s closest neighbours — China, India and Thailand. Asean, the south-east Asian regional grouping to which Myanmar belongs, has called a summit of leaders in Jakarta to discuss the crisis on Saturday. But its invitation to Min Aung Hlaing, the coup leader, while not making any such offer to representatives of the deposed government, has angered many.

Anti-coup politicians — many loyal to the detained Suu Kyi — who evaded arrest and are now in exile or hiding have formed a national unity government that is seeking international recognition and foreign aid. The parallel cabinet includes Karen, Kachin and other minority groups in senior roles.

“We will serve and honour all as brothers and sisters regardless of their race, or religion, or their community of origin, or walk of life,” said Sasa, the shadow government’s minister of international co-operation.

But the rise of a shadow government adds a new layer of complexity as the international community attempts to coax Myanmar away from conflict. While foreign diplomats look at the legal implications of recognition, the anti-coup camp says it needs the world to isolate the junta. Responding to Asean’s invitation of Min Aung Hlaing to the summit, Sasa accused the bloc of engaging with what he called the “murderer-in-chief”.

Neighbourhood watch

Even before the coup, Myanmar was widely being described as a “fragile” state because of its institutional dysfunction and intractable conflicts but some analysts now speak more bluntly about the risk of it becoming a failed state. “It’s a huge problem for the region, and a problem for the international community,” says Richard Horsey, senior adviser to the International Crisis Group. “It’s a human catastrophe, and one that has direct implications on Myanmar’s neighbours.”

Members of the protest camp dislike the “failed state” rhetoric, which they see as fatalistic and emanating from an outside world whose backing can still help them roll back the coup and build a “federal democracy” to address Myanmar’s chronic divisions.

“All the states in Myanmar will become united — you will see it very soon,” says Sasa, the parallel government’s representative. “We just need to overcome this period of darkness . . . it is not going to last that long.”

The signs of trouble, however, are mounting. China — Myanmar’s biggest trading partner and largest arms supplier — has voiced concern over the safety of its oil and gas pipelines that transit the country, after anti-coup activists threatened to attack them in protest against Beijing’s failure to condemn the coup.

The general strike called by the civil disobedience campaign has paralysed government business, crippled the banking system and stifled output in what under democratic rule was one of south-east Asia’s fastest growing economies. International trade has stopped with tens of thousands of workers in logistics, transport, ports, customs clearance and government agencies heeding the strike call. Factories have closed.

Long queues have formed at bank ATMs in recent weeks caused, say businesspeople, by a shortage of cash delivered by the central bank. Strikes by health workers, and their subsequent imprisonment by the regime, have impeded the country’s already inadequate medical system. Schools and universities remain closed.

Several foreign investors have announced plans to leave Myanmar or pause their business. A few — including Japanese beer group Kirin and South Korean steelmaker Posco — were bowing to longstanding calls to end partnerships with military controlled companies, but a more general flight of foreign capital has started. Trade unionists opposed to the coup have urged foreign clothing chains to stop purchases from Myanmar and some have done so, at the cost of about 200,000 jobs, according to one estimate.

The World Bank estimates that Myanmar’s gross domestic product could fall by 10 per cent this year. Fitch Solutions’ forecast is even more dire — a 20 per cent contraction. Both could prove optimistic if more businesses close their doors and foreign investors go elsewhere.

An internal research note commissioned by a domestic bank suggested that in a worst-case scenario: “Myanmar’s name could be added to a list that includes countries from Argentina to Zimbabwe, or Bolivia to Yugoslavia, suffering high or hyperinflation, mass poverty and a currency collapse.”

Air strikes vs homemade rifles

Min Aung Hlaing’s junta has sought to quash news and information flow by shutting down the internet, first ordering telecoms companies to block social media sites, then by severing mobile data and wireless connections. Yet it has failed to stop all reports emerging via independent and social media.

The violence has until now come disproportionately from the regime camp. Breaking up a protest in Bago, north-west of Yangon, two weeks ago the authorities killed 82 people, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a human rights group. The AAPP estimates 739 people have been killed by the junta since February 1 and more than 3,300 people arrested.

In response some protesters have begun arming themselves and hitting back. Such actions, say the anti-coup camp, are a justifiable response to a regime that has used battlefield weaponry against urban demonstrators, including automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenades.

Although these reports cannot be independently verified, they do hint at a rising tide of retribution. In April alone protesters reportedly killed five police officers in an attack in Tamu, near the Indian border, and another three soldiers died after being ambushed by people armed with homemade rifles. In a separate incident, three ethnic groups from northern Myanmar, including the Kachin Independence Army, claimed responsibility for an attack on a police station near Lashio in northern Shan state. Up to 14 police officers were reported killed and the building set ablaze.

Security analysts are for now playing down the protest camp’s ability to inflict lasting damage on the Tatmadaw. There is a huge mismatch in capabilities between one of south-east Asia’s largest armies and people armed with air rifles and petrol bombs, although Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups do have access to weapons caches. This means the scope for violence is much more limited than in Syria, say analysts, where Russia, Turkey and other countries intervened and where according to some estimates as many as 500,000 people, mostly civilians, have died in a decade of war.

“The only way that urban guerrilla warfare might gain some traction would be if ethnic groups were willing to provide even halfway trained kids with weaponry and explosives and encourage them to go back,” says Anthony Davis, a Bangkok-based security analyst with IHS-Jane’s, the defence research group. “Even then, a well sourced military like the Tatmadaw would be capable of crushing it.”

Officials warn of other consequences of the worsening conflict that could tip over into neighbouring countries. The UN reports growing hunger in Yangon’s poorer neighbourhoods, rising narcotics production in Shan state and what they see as an inevitability that more people will flee or be trafficked across national borders.

“Armed groups are undoubtedly watching what’s happening with the conflict in Karen and Kachin,” says Jeremy Douglas, regional representative for the UN’s drugs and crime agency. “If they are to secure themselves and strengthen their positions, they need finance — and the fastest way to do that in Shan and border areas is the drug trade.”

Before the coup, Myanmar’s jungle drugs laboratories — nearly all of which are in Shan state — were estimated to be one of the world’s largest sources of methamphetamine. The narcotic is sold over the border in Thailand and trafficked as far afield as South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, according to UN and police officials. Defence analysts say the Tatmadaw has a history of tolerating drug trafficking by allied militias and “taxing” a cut of the proceeds. They expect the trade to surge, as ethnic armed groups seek sources of revenue to rearm.

At the same time, the UN’s World Food Programme says the disruption to trade has caused rice prices to rise by 5 per cent since January and cooking oil to jump 18 per cent, hitting poor city dwellers the hardest.

“We remain acutely concerned about the impact of the ongoing political crisis, particularly on the ability of the poorest sections of the population to be able to source both sufficient and nutritious food on a daily basis,” says Stephen Anderson, the agency’s Myanmar country director. He says the WFP is particularly concerned about food insecurity in 10 Yangon districts, home to about 2m people, that are either under martial law or have a high prevalence of slum housing.

On Thursday the UN agency estimated that another 1.5m to 3.4m people could be at risk of food insecurity in the next three to six months because of the economic slowdown caused by the political crisis.

While Myanmar has until now grown enough rice to feed itself, the disruption of trade threatens to bankrupt more farmers and deepen what is already a growing food crisis.

“The timeframe that is of particular concern is June, when the planting season begins,” says Nyantha Lin, an independent political analyst and agribusiness expert. “Raw materials such as fertiliser and seed for cash crops are generally imported, and international trade has been severely disrupted.”

‘A band-aid response’

Those watching Myanmar unravel say the international community’s ability to influence developments is finite. “The outside world has limited leverage, the west in particular,” says the ICG’s Horsey. “That doesn’t mean the west should sit on its hands and do nothing, but it means their actions will not have a determinative effect on what happens.”

Since the coup the UN Security Council has passed three resolutions, all backed by Russia or China — which are usually at odds with western members over human rights — that called for an end to violence and the release of detained prisoners. Neither demand has been met.

The US, UK, Canada and the EU have placed sanctions on military leaders and the businesses they control. Some countries have cut off foreign aid or, like Japan, frozen new aid approvals to the junta.

However, even advocates of the sanctions say they will have little effect. While China, arguably the country with the most to lose from the instability, has been guarded in its public statements, Russia has been willing to back the generals publicly.

The resource the generals most lack, say analysts, is legitimacy. This poses a challenge to Myanmar’s diplomatic partners as they seek to broker solutions. Asean has spoken of a need for “dialogue”, a notion that has sparked fury among opponents of the junta who describe it as a brutal and illegal regime.

The unity government is seeking recognition too. Its members have held online meetings with officials from the UK and other countries. Analysts say the international community needs to engage urgently with those resisting the coup, not least to channel emergency aid to the country.

Advocates of this approach point out that the military not only seized power illegitimately, but lacks effective control of the country. However, it would require co-operation from Thailand or India to open the logistics corridors needed to reach the shadow government, says Philipp Annawitt, a governance specialist and consultant who has worked in Myanmar.

“From a humanitarian perspective, you need to build structures that will keep people afloat,” says Laetitia van den Assum, a former Netherlands diplomat. “You have to work with the national unity government, the ethnic armed organisations, and others to make sure there is a safety net in place.”

Analysts say the outside world’s ability to influence events in Myanmar, limited to start with, is narrowing with the rapidly shifting realities on the ground. “Sanctions aren’t going to have any impact in the immediate future — they’re a band-aid response at best, tokenism at worst,” says Davis from IHS-Jane’s. “What will happen is an economic collapse amid escalating conflict.”

[ad_2]

Source link