[ad_1]

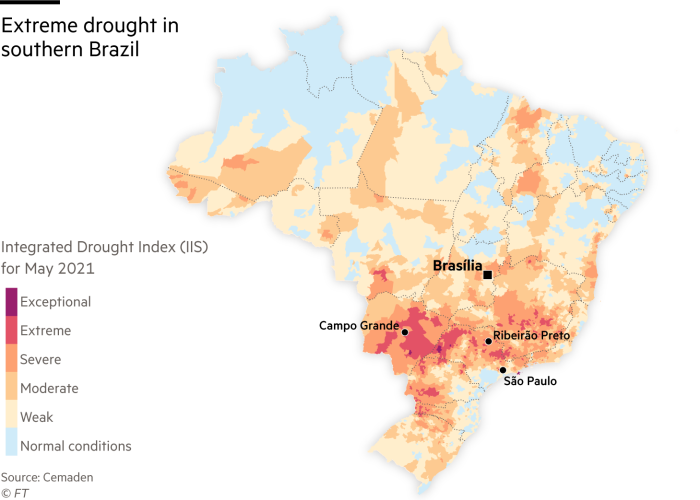

The worst drought in almost a century has caused millions of Brazilians to face water shortages and the risk of power outages, complicating the country’s efforts to recover from the devastating impact of the pandemic. of coronavirus.

Agricultural centers in the state of São Paulo and Mato Grosso do Sul have been worst affected, after the rainy season from November to March produced the lowest level of rainfall in 20 years.

Water levels in the Cantareira reservoir system, which serves about 7.5 million people in the city of São Paulo, fell below one-tenth of its capacity this year. Brazil’s ministry of mines and energy has called the country’s worst drought in 91 years.

“Lately we have been without water every two days, but it was usually night. But on Thursday we had no water all day, ”said Nilza Maria Silva Duarte, from the eastern working class in São Paulo.

José Francisco Goncalves, a professor of ecology at the University of Brasília, said the drought had a devastating effect on the important agricultural industry, which accounts for about 30% of gross domestic product.

“The lack of water in rivers and reservoirs means farmers will not be able to irrigate their land, which will lead to a drop in agricultural production,” he said.

He predicted that the drought “would fuel inflation and commodity prices globally and lower Brazil’s GDP. It has direct repercussions.”

Jose Odilon, a farmer in Ribeirão Preto, a booming agricultural center in the interior of the state of São Paulo, said his sugar cane harvest had been severely affected.

Its vast plantation is littered with heavily automated, largely automated agricultural equipment, to strip the cane of its leaves, harvest its stem and then dump it into a fleet of Mercedes trucks waiting to transport it to the mills. premises.

“We’re going to suffer more because of the lack of moisture in the soil,” he explained. “This really makes development difficult.”

Odilon blamed an inversion of the La Nina weather pattern, which has meant more rain in the Amazon Basin and less in the south of the country.

Marcelo Laterman, a climate advocate for Greenpeace Brazil, said the drought was “directly related” to deforestation in the Amazon, which last year reached its highest level in more than a decade. The forest water recycling system plays a vital role in the distribution of rainfall in South America.

As hydropower accounts for approximately 65% of Brazil’s electricity mix, the drought has also reduced electricity production. This has forced the switch to more expensive thermal energy, which has raised electricity prices for businesses and consumers by up to 40% more this year, according to estimates.

“Our current model based on hydroelectric and thermal power is not sustainable,” Laterman said. “The increase in droughts puts pressure on the reservoirs of hydroelectric power plants and the response we have is the activation of thermoelectric plants, which, in addition to being expensive, increases greenhouse gas emissions and worsens the problem”.

The Brazilian government has warned of possible blackouts and raises fears that energy consumption will be rationed. Local media have reported that the government was preparing a decree on rationing to control the use of electricity in times of scarcity. The Ministry of Mines and Energy said it was discussing energy rationing with “large consumers and industry for times of higher energy demand”.

Silva Duarte said: “Our electricity bill is definitely more expensive and I don’t know how we will do it because our salary has not increased. They said that prices will increase even more. Where will it stop?”

Drought occurs when Brazil faces the economic and social effects of the pandemic. Nearly half a million Brazilians have died Covid-19, the second worst of any country after the United States, and the mortality rate remains above 2,000 per day.

The deployment of vaccines in the country has also been delayed and is only beginning to pick up pace. Just over a quarter of Brazil’s 212 million people have received a first shot.

As consumer prices rise more than 8% year-on-year in May, inflation has combined with high unemployment levels to affect the nation’s poorest citizens.

Less than half of Brazilians have access to adequate food all the time, with 19 million people, or 9% of its inhabitants, suffering from hunger, according to a Brazilian research network on food and nutrition sovereignty and security.

[ad_2]

Source link