[ad_1]

Clothes were once used until they fell apart – they were mended and patched to be reused, ending their lives as dishwashing and oil scraps. Not today. Especially in high-income countries, clothes, shoes, and packaged furniture are increasingly being bought, thrown away, and replaced by new fashions that are themselves soon discarded.

The proof is in the data. In the year In 1995, the textile industry produced 7.6 kg of fiber per person on the planet. In the year In 2018, this doubled to 13.8 kilograms per person – during which time the world’s population increased from 5.7 billion to 7.6 billion. It now buys more than 60 million tons of clothing every year, and this figure is expected to reach 100 million tons by 2030.

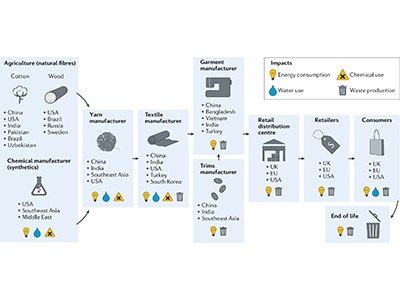

It is called ‘fast fashion’ in part because the fashion industry releases new lines every week, while historically this has happened four times a year. Fashion brands now produce nearly twice as much clothing as they did in 2000. Most of them are produced in China and other middle-income countries such as Turkey, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. Globally, 300 million people are employed in the industry.

But shockingly, more than 50 billion pieces of clothing are thrown away in a single year, according to a report from an expert workshop convened by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published in May.

A landmark agreement on plastic pollution should put scientific evidence front and center

Textiles are divided into two large categories: natural and synthetic. Products made from plants and animals, such as cotton and wool, are mostly stable, although slowly increasing. In contrast, polymer-based fibers, particularly polyester, have grown from 25 million tons per year in 2000 to 65 million tons per year in 2018, according to a NIST workshop report. Combined, these trends are having a dramatic environmental impact.

Take water. The fashion industry, one of the world’s largest water users, consumes between 20 trillion and 200 trillion liters each year. Then there are microplastics. Plastic fibers are released when we wash polyester and other polymer-based fabrics, and 20% to 35% of microplastics choke the oceans. Added to this are certain chemicals, such as those used to make fabrics resistant and pesticides needed to protect crops such as cotton.

Change is desperately needed, but the fashion industry will need to work hard to further embrace what is known as the circular economy. That involves at least two things: refocusing on making things sustainable and encouraging reuse. and the rapid expansion of technologies for sustainable manufacturing processes, especially recycling. There is an important role for research – both academic and industrial – to achieve these and other aspirations.

Researchers can start by helping to provide more accurate estimates of water use. It should be able to narrow down the range to between 20 trillion and 200 trillion liters of water. There is also work to improve and expand textile recycling. Too much, used textiles end up in landfills (in the United States, the rate is around 85%), in part because there are (relatively) few systems that collect, recycle, and recycle the materials. Such recycling requires manual separation of fibers, as well as buttons and zippers. Different fibers are not easy to distinguish by eye, and generally such manual processes are time-consuming. Machines are being developed that can help. Technologies also exist to chemically recycle used fibers and create high-quality fibers that can be reused in clothing. But these are nowhere near the desired amount.

Another challenge for researchers is working out how to get consumers and producers to change their behavior. This is already an active area of study in the social and behavioral sciences. For example, at the University of Bonn in Germany, Verena Tiefenbeck and her colleagues found that when hotel guests were given real-time feedback on the energy they used to take a shower, they reduced their energy consumption by 11.4%.1. Other research questions include finding ways to encourage people to buy sustainable goods. exploring how to satisfy demand for innovation while minimizing environmental impact; and understanding why some interventions can be scaled up successfully and others fail.

Fast fashion local value

Industry and academia could also collaborate to develop a system to monitor textile microplastics. This can be done digitally, for example. It requires an agreed definition of textile microplastics, such as their material composition and sizes. Companies, universities, campaigners and governments need to think about how to make their technologies more accessible. Doing so accelerates development and testing and (eventually) mass adoption.

There are also schemes that can be a source of ideas in other fields. The WHO has extensive experience when it comes to access, for example on rapid access to Covid-19 equipment. Through this, companies and governments agree on principles for sharing key technologies in research and drug development. In the early 2000s, the Rockefeller Foundation made a major push to encourage companies to share agricultural biotechnology technologies by establishing the African Agricultural Technology Foundation at Imperial College London under then-President Gordon Conway. These plans are not perfect and are continually evolving, but they provide ideas and lessons to be studied and considered.

In the meantime, campaign groups are mobilizing alongside industry. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a UK-based charity that promotes circular solutions, is seconding the Jeans Redesign campaign, which challenges clothing manufacturers to offer circular solutions for that every wardrobe. Some manufacturers have improved their jeans manufacturing process by using organic cotton in a circular shape and inserting a zipper so that the garments can be easily removed during recycling. Others are using reinforced stitching to make their products last longer. These are important proofs of principle, but such methods must be primary.

These practices add value and defy the idea of fast fashion, as they make goods less affordable to consumers who want to keep up with the latest trends. Brands and retailers take risks to their bottom lines seriously (and may choose to delay action on the sustainability of the results). This is why government action is key.

Policies need precision and teeth, which the current ones don’t always have, and they need to be coordinated. The EU’s advice to member states states that by 2030 there should be “minimums for the inclusion of recycled fibers in textiles, which are durable and easy to repair and recycle”. This is very vague. Without more specific targets, tracking for compliance purposes becomes more difficult. China, the world’s largest textile producer, has a five-year circular economy plan for the industry. Given the rapid convergence of fashion, China and the EU should work hard to coordinate their efforts with the US and others.

Small steps are good, but big changes are needed. There is no time to waste in changing textile manufacturing and design. Embarrassing environmental spending must be tackled with a new dance wardrobe, modestly, stylishly and quickly.

[ad_2]

Source link