[ad_1]

I’m a 29-year-old gay man living in New York City during the first major wave of monkeypox infections in the United States. As the CEO and co-founder of a health care startup, I am very connected to the world of public health — especially public health that impacts LGBTQ+ people.

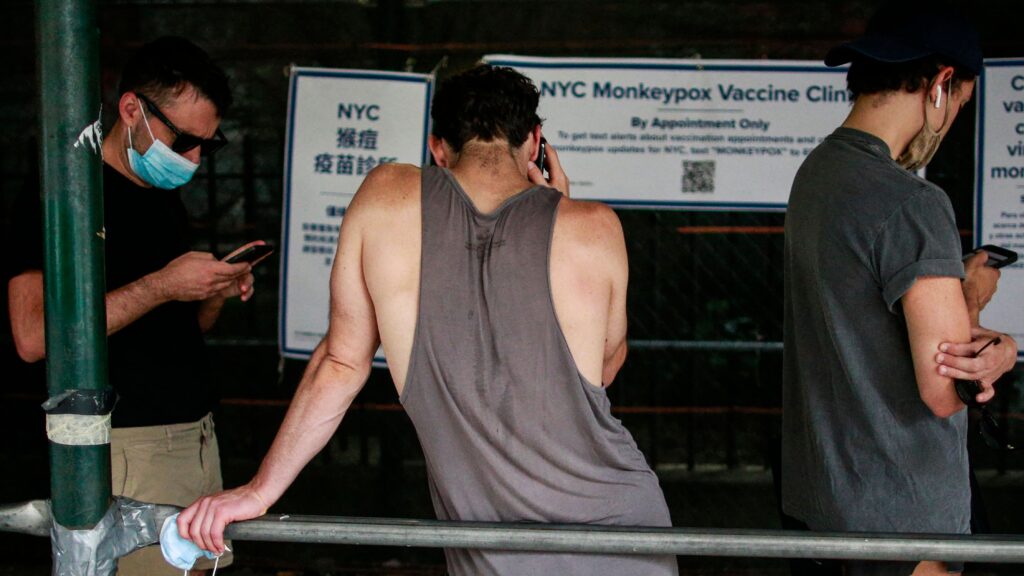

So I assumed I could get vaccinated against monkeypox fairly easily. But it took me weeks to do that. It’s even more difficult for people in my community with less time and fewer resources. What can be done to fix this?

I stepped off the 4 train into a huge crowd of masked strangers at the Bedford Park Boulevard subway station in the Bronx. Old men, young men, trans people, able-bodied and disabled people: all of us were on our way to get vaccinated at the Bronx High School of Science.

advertisement

To get to that point, I had to identify my own health risk. Some of the questions — Was I having enough promiscuous sex to qualify for vaccination? Had I had anonymous sex? Was it unprotected? With multiple partners? Where did you meet? In the last two weeks? — I wouldn’t want to answer in front of my closest friends. Not to mention, who gets to decide what “promiscuous sex” is anyways?! It’s not a factual term, but one full of judgment.

Next, I had to seek out appointments online and get one before they ran out, a time-consuming task.

advertisement

In the crowd headed to the Bronx High School of Science, it felt surreal to see people who had survived AIDS in the 1980s next to my generation of LGBTQ+ people. While HIV is no longer a death sentence with access to the right preventive measures (PrEP) and treatment (antiretroviral therapy), the community trauma remains. We were coming from every part of New York City to protect ourselves, our communities, and the public at large.

When I opened my Grindr app (a location-based social networking and online dating application for gay, bi, trans, and queer people), I was shocked to see hundreds of people online in my immediate vicinity. The Bronx High School of Science is not a typical stop for the LGBTQ+ community on Sundays — it’s not brunch in Manhattan’s West Village — but we were moved to travel outside our neighborhoods and boroughs for a common purpose. My friends and I have noticed that people who use Grindr have started not only flagging their Covid vaccination status but their monkeypox vaccination status as well. Grindr is even encouraging users to get a vaccine. (You know that public health has dropped the ball when a gay hookup app is promoting vaccination before local or national public health agencies.)

It’s obvious to me — and should be clear to anyone — that the LGBTQ+ community wants to do its part to stop the spread of monkeypox. But just as PrEP is a necessary tool to limit the spread of HIV, other public health tools are also needed to combat monkeypox.

One of the older guys in line, probably in his mid-60s, was wearing a shirt bearing the iconic ACT UP slogan “SILENCE = DEATH” underscoring the connection between the AIDS epidemic and this monkeypox outbreak. While self-identification unfairly puts the onus on LGBTQ+ people to access health care services, what other groups boast this level of health awareness? With Covid-19, individuals were expected to protect themselves, but there was a larger expectation for public health to provide additional tools like remote diagnostic testing, realistic protocols and guidelines, and, eventually, easily accessible vaccines. With monkeypox, both the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have asked men who have sex with men to decrease or halt sexual activity with new partners and get vaccinated, despite offering little information on how to do either.

There is a limit to what the LGBTQ+ community can accomplish without greater institutional support. (Hello, federal government! What have you been doing? Robert Fenton was appointed as the White House monkeypox coordinator, but not until three states had already declared state of emergencies.)

The first clinic in New York City, in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, to offer 1,000 doses of monkeypox vaccine had to close its line after about 90 minutes. The San Francisco Department of Health confirmed that city clinics ran out of monkeypox vaccines in less than a day in early August. Georgia emerged as a monkeypox hotspot, but health department websites routinely crash when vaccination appointment links go live due to overwhelming demand, leaving many citizens no closer to a vaccine than before.

When I got in to see a nurse at the Bronx High School of Science, there was some confusion over whether I’d be able to get a second vaccine dose. At the time, public health officials were trying to decide if they should stretch the vaccine supply by vaccinating more people with one dose rather than fully vaccinating fewer people with two doses, resulting in protection for the immediate future but less long-term durability.

After my first vaccination, the Biden administration authorized use of one-fifth doses of the Jynneos monkeypox vaccine. While this seems like a good idea, health care workers are having difficulty learning how to administer the vaccine intradermally as required, routinely resulting in wasted doses. Why was this plan authorized before health departments could operationalize the fractional dosing plan effectively?

Lack of vaccines isn’t the only problem. Monkeypox testing is limited and the WHO and CDC are encouraging people to limit sexual partners, which is not an effective long-term solution. Note the enormous spike in sexually transmitted infections during Covid-19, including a 24% increase in the rate of primary and secondary syphilis among reproductive-aged women at a time when people were supposed to be social distancing. (Also, imagine straight people being singled out to stop having sex as a public health measure!)

Testing also needs to be more accessible. Health departments across the nation should consider enabling at-home diagnostics for monkeypox to help the LGBTQ+ community at large fight the spread. This would allow at-risk members of this community to access care without public self-identification, as well as reach parents, shift workers, individuals with disabilities and others who might not have resources to seek care outside the home. The Center for American Progress reported that 31% of LGBTQ+ people living outside of metropolitan areas would find it very difficult or impossible to access more than one community health center or clinic.

Some hospitals, clinics, and public health initiatives have built on the popularity of telehealth, use of which increased more than 150% during the Covid-19 pandemic, to improve access to health care with ongoing telemedicine options and at-home diagnostic testing. Home diagnostics are currently used in STI testing, fertility screening, primary care, medication management, chronic care, and more. Why not use this option to increase access to monkeypox testing and remote care, especially when multiple studies (Kaiser Family Foundation, Rutgers University, and others) show telehealth is an effective way to reach the LGBTQ+ community? An FDA-approved monkeypox test can detect monkeypox from a lesion sample, which is not dissimilar to a test for herpes.

The larger public health community needs to take action to stop monkeypox as it did with Covid-19 — free vaccines for all, improving access through telehealth, enabling an Operation Warp Speed to speed up development of monkeypox vaccines and therapies, and major information campaigns to spread awareness about the disease. The LGBTQ+ community has largely had to advocate for itself, as it continues to do with the AIDS epidemic. It’s time for greater institutional support to keep the virus contained.

David Stein is the CEO and co-founder of Ash Wellness, a New York City-based company that works with partners to enable at-home testing programs.

[ad_2]

Source link