Lung Cancer in Never-Smokers Is Rising — and Scientists Say It Needs Urgent Research Attention

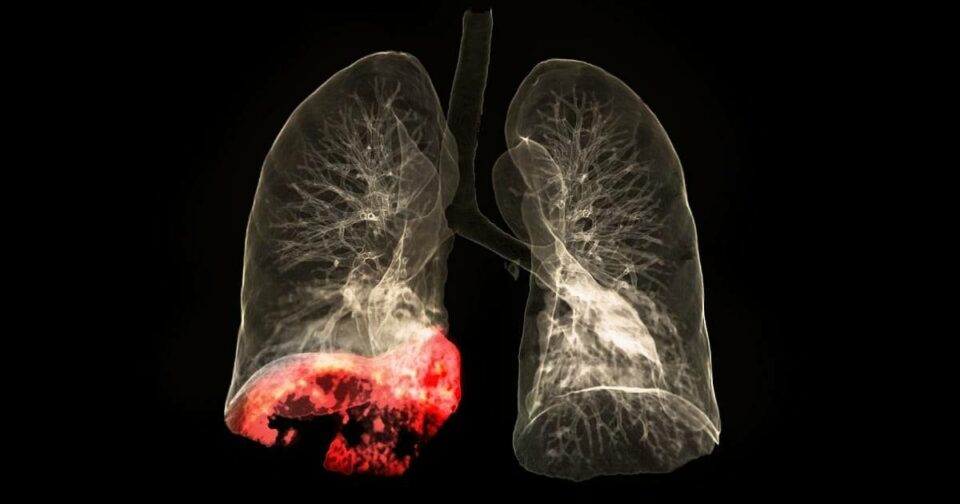

London, United Kingdom — Lung cancer has long worn the label of a “smoker’s disease,” but that assumption is increasingly dangerous. A growing body of evidence confirms that lung cancer in people who have never smoked (LCINS) is rising globally—and scientists warn that research, screening, and treatment paradigms have failed to keep pace.

A major review led by researchers at University College London (UCL) , published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, issues an urgent call to action: LCINS is not merely a subset of lung cancer. It is a distinct disease with different biology, different risk factors, and different treatment responses—yet it remains critically understudied and systematically overlooked.

More Cases, Less Attention

In 2020, lung cancer in never-smokers was already the fifth leading cause of cancer death worldwide—a ranking that surprises many clinicians and public health officials accustomed to associating lung malignancy almost exclusively with tobacco.

As smoking rates decline across high-income countries due to successful public health campaigns, the proportion of lung cancer cases occurring in never-smokers is rising. But the trend is not merely proportional. Absolute numbers are increasing.

A UK study documented that never-smoker lung cancer cases doubled between 2008 and 2014. Data from the United States confirms similar trajectories. Yet screening programmes remain overwhelmingly focused on current and former smokers.

In the United Kingdom, there is no routine lung cancer screening for never-smokers. In the United States, eligibility criteria for low-dose CT screening heavily weight smoking history. The result is predictable: never-smokers are diagnosed later, when treatment options are limited and survival outcomes significantly poorer.

A Different Disease Entirely

The UCL review emphasizes that LCINS is not simply lung cancer without a smoking history. It is biologically distinct.

Histology:

Never-smokers are disproportionately affected by adenocarcinoma, a subtype that typically arises in the outer regions of the lungs rather than central airways. This growth pattern influences symptoms, detection, and metastatic behavior.

Genomics:

Approximately 80 per cent of adenocarcinomas in never-smokers harbor identifiable driver mutations—genetic alterations that directly promote cancer growth. These include:

-

EGFR mutations — Particularly common in East Asian populations and younger women

-

ALK rearrangements

-

ROS1 fusions

-

RET and MET alterations

This genomic landscape presents a significant therapeutic opportunity. Many of these mutations are actionable—targeted therapies exist that can achieve remarkable responses. However, identifying these patients requires routine molecular testing, which remains inconsistent across healthcare systems.

Immunotherapy Response:

Paradoxically, while never-smokers are more likely to benefit from targeted therapies, they tend to respond less well to immune checkpoint inhibitors—drugs that have revolutionized treatment for smoking-related lung cancers. This differential response underscores the critical importance of treatment stratification based on biology, not smoking history alone.

Risk Factors Beyond the Cigarette

If not smoking, what drives these cancers? The UCL review identifies multiple contributing pathways:

Inherited Genetics:

Up to 4.5 per cent of never-smokers with lung adenocarcinoma carry germline mutations that predispose to cancer development. The EGFR T790M mutation, for example, can be inherited and leads to earlier-onset, multifocal disease. Variations in immune-related genes such as the APOBEC3 family also confer increased susceptibility.

Clonal Hematopoiesis:

Age-related accumulation of mutations in blood stem cells—a condition called clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) —drives chronic inflammation that creates a permissive environment for lung cancer development. This risk operates independently of smoking exposure.

Environmental Exposures:

While not the focus of the UCL review, independent epidemiological research confirms that ambient air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), significantly elevates lung cancer risk in never-smokers. The effect is most pronounced in densely populated urban centers with poor air quality.

Prior Lung Disease:

A history of tuberculosis or chronic bronchitis has been associated with increased LCINS risk, possibly through chronic inflammatory pathways that promote genomic instability.

The Clinical Recognition Gap

Perhaps the most urgent challenge is cognitive. Lung cancer simply does not appear on many clinicians’ differential diagnosis when evaluating a never-smoker—particularly a young woman—presenting with respiratory or nonspecific symptoms.

One expert involved in the review described a recurring pattern: shoulder pain, mild cough, unexplained weight loss. Multiple consultations. Antibiotics prescribed. Physiotherapy initiated. Lung cancer considered only after metastatic disease is discovered.

Each delay represents a missed opportunity for cure. Early-stage lung cancer treated surgically carries an excellent prognosis. Late-stage disease, even with modern therapies, does not.

What Needs to Change

The UCL researchers propose a comprehensive, multi-domain strategy for addressing LCINS:

1. Screening Reform:

Risk prediction tools designed specifically for never-smokers must be developed and validated. Low-dose CT screening protocols should be evaluated in this population, with appropriate age thresholds and risk stratification.

2. Molecular Access:

Universal reflex testing for EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and other actionable mutations should be standard of care for all lung adenocarcinoma patients—regardless of smoking history. Geographic and socioeconomic disparities in biomarker testing must be eliminated.

3. Dedicated Clinical Trials:

LCINS patients are underrepresented in therapeutic trials, and efficacy data from smoking-predominant populations may not generalize. Biology-driven, histology-agnostic trials focused on never-smoker populations are urgently needed.

4. Environmental Health:

Air pollution mitigation, radon testing and remediation, and second-hand smoke exposure reduction remain essential public health interventions with direct relevance to LCINS prevention.

5. Anti-Inflammatory Strategies:

For high-risk individuals identified through genetic screening or clonal hematopoiesis assessment, anti-inflammatory interventions warrant investigation as chemoprevention.

Breaking the Smoking-Centric Paradigm

The persistence of smoking-centric thinking in lung cancer is understandable—tobacco is the dominant risk factor globally, and smoking cessation remains the most effective prevention strategy. But dominant is not exclusive.

As smoking rates decline, the relative and absolute importance of non-smoking risk factors will continue to grow. Healthcare systems that fail to adapt will increasingly miss opportunities for early detection, targeted therapy, and prevention.

Professor Charles Swanton, a senior author of the UCL review, frames the challenge directly: “We cannot continue to think of lung cancer as a single disease defined by a single risk factor. The biology tells us otherwise. The epidemiology tells us otherwise. Our research and clinical frameworks must catch up.”

Also Read: RSS Chief’s Remark on Salman Khan’s Influence on Youth Fashion Goes Viral

Conclusion: A Disease in Its Own Right

Lung cancer in never-smokers is not an epidemiological curiosity or a minor subset of a tobacco-centric disease. It is a major, growing, and distinct oncological entity with unique biology, distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities, and specific prevention opportunities.

The fifth leading cause of cancer death worldwide deserves more than fifth-class research priority.

Screening must expand. Molecular testing must universalize. Clinical trials must include. And the assumption that lung cancer is a smoker’s disease—held by clinicians, policymakers, and patients alike—must finally be retired.

The science is clear. The cases are mounting. The urgency is now.

LCINS is not rare. It is not marginal. And it is not being adequately addressed.