[ad_1]

A police officer is at the scene of a murder. No witnesses. No camera footage. No obvious suspects or motives. Just a bit of hair on the sleeve of the victim’s jacket. DNA from the cells of one strand is copied and compared against a database. No match comes back, and the case goes cold.

Corsight AI, a facial recognition subsidiary of the Israeli AI company Cortica, purports to be devising a solution for that sort of situation by using DNA to create a model of a face that can then be run through a facial recognition system. It is a task that experts in the field regard as scientifically untenable.

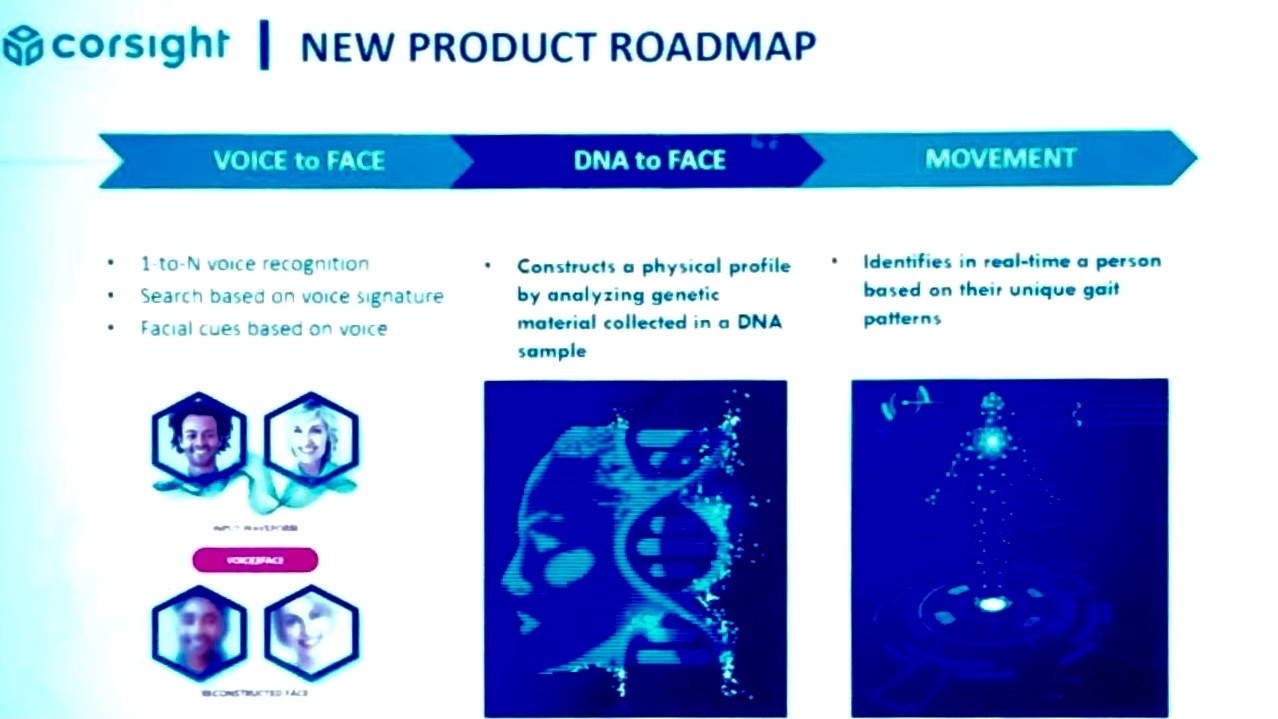

Corsight unveiled its “DNA to Face” product in a presentation by chief executive officer Robert Watts and executive vice president Ofer Ronen intended to court financiers at the Imperial Capital Investors Conference in New York City on December 15. It was part of the company’s overall product road map, which also included movement and voice recognition. The tool “constructs a physical profile by analyzing genetic material collected in a DNA sample,” according to a company slide deck viewed by surveillance research group IPVM and shared with MIT Technology Review.

Corsight declined a request to answer questions about the presentation and its product road map. “We are not engaging with the press at the moment as the details of what we are doing are company confidential,” Watts wrote in an email.

But marketing materials show that the company is focused on government and law enforcement applications for its technology. Its advisory board consists only of James Woolsey, a former director of the CIA, and Oliver Revell, a former assistant director of the FBI.

The science that would be needed to support such a system doesn’t yet exist, however, and experts say the product would exacerbate the ethical, privacy, and bias problems facial recognition technology already causes. More worryingly, it’s a signal of the industry’s ambitions for the future, where face detection becomes one facet of a broader effort to identify people by any available means — even inaccurate ones.

This story was jointly reported with Donald Maye of IPVM who reported that “prior to this presentation, IPVM was unaware of a company attempting to commercialize a face recognition product associated with a DNA sample.”

A checkered past

Corsight’s idea is not entirely new. Human Longevity, a genomics-based, health intelligence company founded by Silicon Valley celebrities Craig Venter and Peter Diamandis, claimed to have used DNA to predict faces in 2017. MIT Technology Review reported then that experts, however, were doubtful. A former employee of Human Longevity said the company can’t pick a person out of a crowd using a genome, and Yaniv Erlich, chief science officer of the genealogy platform MyHeritage, published a response laying out major flaws in the research.

A small DNA informatics company, Parabon NanoLabs, provides law enforcement agencies with physical depictions of people derived from DNA samples through a product line called Snapshot, which includes genetic genealogy as well as 3D renderings of a face. (Parabon publishes some cases on its website with comparisons between photos of people the authorities are interested in finding and renderings the company has produced.)

Parabon’s computer-generated composites also come with a set of phenotypic characteristics, like eye and skin color, that are given a confidence score. For example, a composite might say that there’s an 80% chance the person being sought has blue eyes. Forensic artists also amend the composites to create finalized face models that incorporate descriptions of nongenetic factors, like weight and age, whenever possible.

Parabon’s website claims its software is helping solve an average of one case per week, and Ellen McRae Greytak, the company’s director of bioinformatics, says it has solved over 200 cases in the past seven years, though most are solved with genetic genealogy rather than composite. analysis. Greytak says the company has come under criticism for not publishing its proprietary methods and data; she attributes that to a “business decision.”

Parabon does not package face recognition AI with its phenotyping service, and it stipulates that its law enforcement clients should not use the images it generates from DNA samples as an input into face recognition systems.

[ad_2]

Source link