[ad_1]

Ali Carnegie, a business energy broker in southwest England, spends most of his working day on the phone, which is bad news for clients.

In normal times, Carnegie has single-digit percentage increases in the consumption of more than 250 small and medium-sized enterprises on its books, along with gas and electricity suppliers. But now that energy bills are starting to rise sharply, mainly due to Russia’s increased gas supplies to Europe, he has to recommend contracts that could put some of his clients’ businesses out of business.

Last month, the hospitality business he works with was awarded a new electricity contract worth £605,000 a year, seven times more than before. The owners are now working to see if their business can continue to grow.

Spiraling energy costs are one of the many pressures weighing on the UK’s 5.5mn small businesses. Carnegie, who runs Cornwall-based consultancy Total Energy Solutions, said: “If energy prices alone went up, this winter would have been miserable.

Rising wage bills, higher raw material costs, supply chain disruptions and Brexit will only add to the pressures. The bottom line is that many SMEs, which employ three-fifths of the UK workforce, would probably fail without government intervention.

In the year In 2020, the first year of the outbreak, the UK lost around 390,000 small businesses, more than one-twentieth of the total. Tina McKenzie, policy chair of the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB), predicted this winter would be “simply devastating”. . . If not worse”.

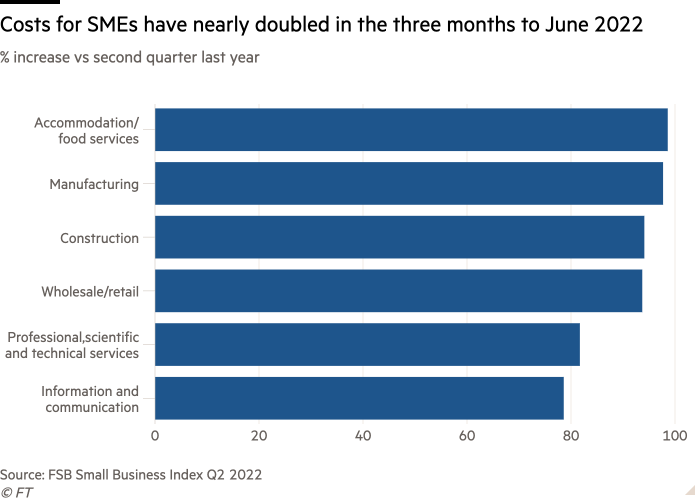

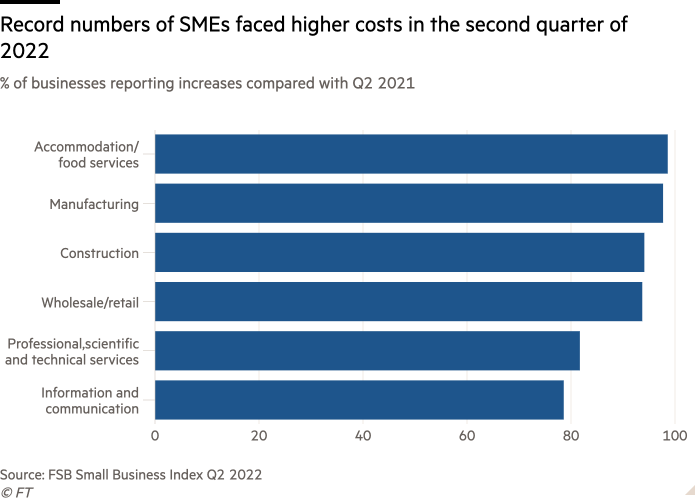

In the three months to June 30, SMEs in the hospitality, manufacturing, construction and retail sectors all reported input costs that nearly doubled from the same quarter last year, according to the FSB’s Small Business Index.

In the same period, 5,629 company bankruptcies were recorded in England and Wales, a 13% increase on the previous quarter.

Andrew Goodacre, chief executive of the Association of British Independent Retailers, said: “The government needs to wake up to the real crisis facing small businesses.” “If you restrict business, you will be harmed. That’s hard to recover from.”

Industry groups have called on ministers to help small businesses with their energy bills over the winter and offer full business rate relief.

In the race to replace Boris Johnson as Prime Minister, both candidates have made limited commitments to help small businesses. Frontrunner Liz Truss has pledged to scrap the proposed rise in corporation tax, while Rishi Sunak has pledged to extend the 50 per cent cut in business rates.

A government spokesman said: “No national government can control global conditions that are driving up energy prices, but we will continue to support business in the coming months.”

Last week, as temperatures soared again, family-owned Cornish ice cream maker Roskilde celebrated its best day of trading since it began selling the treat 35 years ago. But the outlook is less sunny.

Its 60 workers have received a 10 percent pay rise and the company has been denied a contract renewal by its energy supplier, which could leave it at the mercy of rapidly rising variable tariffs in October.

Producing and freezing 400,000 liters of ice cream a year is an energy intensive enterprise. With a margin of 4 per cent, which translates to £2.3mn a year, the company is heading for a huge loss.

“The workers are very scared because if I don’t have the money, I will have to reduce hours or work during the winter,” said Silke Roskilde, one of the directors.

In the energy market, small businesses have been “thrown to the wolves”, argues FSB’s Mackenzie. While consumers enjoy some protection from energy price caps and state funding, and large corporations can hedge against energy costs, SMEs are an “easy target” for suppliers, she added.

“If you’re an energy company, where do you get your big walk? Small businesses, because there’s no protection,” McKenzie said.

A particularly tight labor market is conspiring to hit the hospitality industry hard, with rising energy, food and beverage costs. The food and accommodation sector has an 8 per cent vacancy rate, the highest of any industry, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Earlier in the summer, Anthony Pender, co-owner of Yummy Pub Co., which has three sites in London and southeast England, was so short-staffed that he was pulling pints himself. Now the staffing levels have increased but the company’s salary has increased from 26 to 31 percent. The biggest purveyor of draft lager has increased prices by a quarter and its electricity bill has doubled.

“We can’t pass those costs on because we don’t have any customers,” Pender said. He warned of the need to cut back on business hours over the winter, trim the menu and lay off chefs to save money.

“I think we’re headed for a catastrophic market event. Our business survives on £5mn turnover, but how will Dick and Rita survive when they turn over a few thousand a week at Dog and Dack?

Yumi Pub Co. has a rare four-month cash reserve for businesses in the sector affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. As part of the UKHospitality (UKH) business unit, one in six hospitality businesses has no reserves.

The British Innking Institute calculates that independent pubs will need to trade 20 per cent more than they did before the pandemic, but 86 per cent are turning a profit at 2019 levels.

UK CEO Kate Nicholls said: “Not all businesses will survive this onslaught, and those that can will be thinking closely about how to cut costs to stay afloat.”

In the seaside town of Leamington in southern England, Raoul Parfitt, managing director of organic hair dye manufacturer Herb UK, is trying to work out how to spend the summer.

Post-Brexit, the increased cost of exports to the EU, which accounts for a fifth of revenue, has already cut into margins. But in recent months, the price of essential raw materials has increased significantly, in some cases up to five times.

The company, which employs more than 50 people in the UK and has an annual turnover of £7.5m, has tripled its electricity costs. Fortunately, Herb moved to a new, more efficient location in January. “It would be horrible if we were still in the old room,” Perft said. “We have invested heavily in smaller production units for more efficient boilers. . . So we’re trying to simplify as much as we can.

As they steel themselves for a major downturn this winter, many small businesses are vying for leadership amid a policy vacuum over how much help they will get from the UK’s new prime minister.

The FSB’s McKenzie said: “It looks like we’re on the pause button as everyone moves into the winter frenzy.”

[ad_2]

Source link