[ad_1]

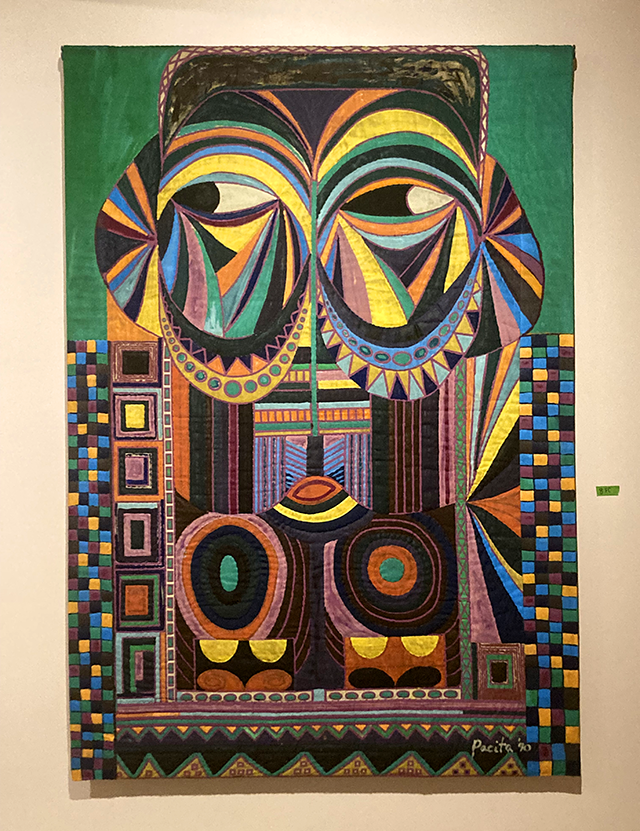

The Gallery Room at the Walker Art Center features a retrospective exhibition of Pacita Abad’s 32-year career, including works from Abad’s “Bacongo” series, a region in central Africa that now includes the Republic of the Congo and the Dominican Republic. The paintings resemble beefweb masks made by the Sonye and Luba ethnic groups. They are huge paintings made on a flat surface and stuck on canvas. Each mask draws inspiration from different parts of the world, but according to Walker Curatorial Associate Matthew Villar Miranda, they have a subtle political perspective.

“What’s bought is who she chooses to highlight and why,” says Villar-Miranda. “The Hopis were not traditionally chosen to represent the North American continent. Mayan is not traditionally chosen to represent South America. She is in fact an inversion of the concepts of global north, global south, and represents equality as central.

Abad also made European masks, although Europe “isn’t particularly known for its masking culture,” says Villar Miranda, citing Abad’s comment about his work: “You sum it up.” We will sum it up.”

Abad creates her mask work using her signature trapunto technique, a process that involves sewing fabric onto canvas and hand-embellishing with buttons, shells, and other embellishments.

“It was a technique she learned from a friend and she innovated,” said Victoria Sung, Walker’s associate curator of visual arts, who organized the exhibit. She would paint her canvases with acrylic or oil, and instead of stretching that canvas on a frame as usual, she would add backing and wrapping and accessories and sew it all by hand.

Much of Abad’s career has been spent traveling across six continents with her husband, Jack Garrity, an international development economist. The two met at a world affairs conference in Monterey, California, where they were both students representing schools. After they met, they spent a year traveling to various art shows throughout Asia. During their time together, they spent time in Sudan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Dominican Republic and many other places.

MinnPost photo by Sheila Regan Abad’s “Bakongo” series of paintings resemble beefweb masks made by the Sonye and Luba ethnic groups.

“I’ll drop her off at the village in the morning and tell her I’ll be back in seven hours,” Garrity told me. “When I return to the village, I look for the people, so I have never had a problem finding her. They all watch.

At first, Garrity Abad says he works with simple canvas. But because they were traveling so much, that method became difficult. “We had a big fight on one of them because I had to carry and wrap.” Later, Abad began to paint by arranging canvases on the floor or walls. When she’s done, she wraps them up with an idea from a Tibetan refugee camp in Nepal called Thangka. The works can be rolled up like a quilt, making them more portable than a canvas stretched on a frame.

Abad’s trapunto process was arduous, and it was told in many places Abad visited. “She worked, worked, traveled to more than 60 countries in her life,” Sung said. “In all these geographies, she picked up different materials, different techniques and incorporated them into her work. So they’re really amazing, a cornucopia of global diversity.”

In addition to Abad’s trapunto paintings, the exhibition at the Walker – which the museum has organized with Abad’s estate – deals with works on paper, clothing and ceramics. There are paintings of clothes she “borrowed” from her husband, Jack, that share the narratives of immigrant communities, especially women of color, and often political works where she highlights her history (i.e., communities not often represented in mainstream narratives). Abad’s “LA Liberty” Trapunto painting, depicting an immigrant woman as the Statue of Liberty, is a major painting that places immigrant women at the center of American symbolism.

MinnPost photo by Sheila Regan There are paintings on clothes that Pacita Abad “borrowed” from her husband Jack.

“Pasita Abad was an incredibly accomplished artist,” said Walker Executive Director Mary Cerutti. “She dabbled in a wide variety of subjects, and created diverse compositions from colorful masks, intricate underwater scenes, and abstract writing.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Abad’s work is often undermined by racism and sexism. In her 1986 review of Abad’s “Underwater Desert” exhibition at the Ayala Museum in the Philippines, one critic wrote more about Abad’s fashion choices than her artwork. “Pasita Abad is a woman whose art is primitive and rough, but whose strength is her personality, which appeals to the idea of a ‘wild’ bohemian lifestyle,” the review said.

Such a reduction of a woman’s ability to color is similar to another artist: Frida Kahlo, whose personality and biography have been enhanced by the endless childishness of popular culture.

In her essay in the catalog accompanying the exhibition, Sung notes that Abad’s work has rarely been in the context of addressing the same subject matter as her peers—Howard, Pindell, Carlos Villa, and Jimmy Durham, who in 2017 also sparked controversy in the Walker retrospective. I understand Durham Cherokee identity…

Walker’s retrospective is an attempt to right that historical wrong by creating more than 100 objects—never before seen in America—of Abad’s contributions, as well as an extensive catalog of Abad’s work. Although he celebrates the joy of the artist, the joy of color, culture, people and creativity, he takes Abad seriously as an artist.

“Pasita Abad” runs through Sept. 3 at the Walker Art Center ($18). More information here.

[ad_2]

Source link